Τζαμί του Σάχη, Ισφαχάν (1629): το Ωραιότερο, το πιο

Εντυπωσιακό, το πιο Υπερβατικό Μνημείο του Κόσμου

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/07/21/τζαμί-του-σάχη-ισφαχάν-1629-το-ωραιότερο/

==============

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Τζαμί του Σάχη, Ισφαχάν (1629): το Ωραιότερο, το πιο Εντυπωσιακό, το πιο

Υπερβατικό Μνημείο του Κόσμου

Μπορεί να είμαι Χριστιανός Ορθόδοξος, αλλά

το μνημείο που με έχει εντυπωσιάσει περισσότερο στη ζωή μου είναι το

αυτοκρατορικό σαφεβιδικό τζαμί του Ισφαχάν που ανεγέρθηκε πριν από μόλις 400

χρόνια – 390 για την ακρίβεια.

Πολλοί δυτικοί επισκέπτες είναι γνωστό ότι

εντυπωσιάζονται ιδιαίτερα από το Τατζ Μαχάλ στην Ακμπάρ Αμάντ (σήμερα γνωστή ως

Άγκρα) κοντά στο Δελχί της βόρειας Ινδίας που ήταν η πρωτεύουσα της Μογγολικής

Αυτοκρατορίας των Γκορκανιάν, μιας ισλαμικής αυτοκρατορίας που για αιώνες ήταν

τόσο ισχυρή όσο το Σαφεβιδικό Ιράν και το Οθωμανικό Χαλιφάτο.

Άλλοι πάλι μένουν έκθαμβοι από το Μπλε

Τζαμί, το γνωστό Σουλτάν Αχμέτ της Σταμπούλ, το οθωμανικό αρχιτεκτονικό

αντίβαρο της ρωμαϊκής χριστανικής Αγίας Σοφίας.

Και όσοι είχαν την τύχη, όπως εγώ δυο

φορές, να βρεθούν στην τουρανική πρωτεύουσα του Ταμερλάνου, την Σαμαρκάνδη

(επίσης γνωστή και ως Αφρασιάμπ) στο Ουζμπεκιστάν, ασφαλώς και εκστασιάσθηκαν

όταν βρέθηκαν στο Ρετζιστάν με τις τρεις ισλαμικές θρησκευτικές σχολές – πανεπιστήμια

– βιβλιοθήκες – ερευνητικά κέντρα που επίσης στεγάζουν τζαμιά με μιναρέδες.

Ένα μνημείο δεν είναι μόνον ένα υλικό αντικείμενο. Είναι επίσης το

γενικώτερο πλαίσιο στο οποίο βρίσκεται ως γη, ως χώρος και ως ενδεχομένως

συνάρτηση και άλλων μνημείων κι αρχιτεκτονημάτων. Είναι επίσης οι ψυχικές

αναζητήσεις των μεγάλων σχεδιαστών κι αρχιτεκτόνων που συνέλαβαν το μνημείο ως

εικόνα και την μορφοποίησαν.

Είναι επίσης οι συμβολισμοί και οι αξιωματικές αλήθειες που κρύβονται στην

αρχιτεκτονική δομή του: από την Αρχαία Αίγυπτο και Μεσοποταμία όλα τα ναϊκά

αρχιτεκτονήματα και θρησκευτικά μνημεία έπρεπε να αποτελούν την υλοποίηση μιας

ιδιαίτερης ερμηνείας του αξιώματος ‘όπως επάνω έτσι και κάτω’. ‘Κάτω’ είναι ο

προσωρινός υλικός κόσμος στον οποίο ζούμε και ‘επάνω’ είναι ο αιθερικός κόσμος

τον οποίο ο Ιησούς αποκάλεσε ‘Βασιλεία των Ουρανών’.

Ένα σημαντικό, αρχετυπικό, ναϊκό αρχιτεκτόνημα δεν είναι μια απλή αναζήτηση

καλλιτεχνικής ομορφιάς και αρμονίας όπως συχνά επιχειρήθηκε στην Αρχαία Ελλάδα.

Δεν είναι ένα απλό οικοδόμημα όπου συσσωρεύονται αγάλματα, ανάγλυφα, εικόνες κι

άλλες αναπαραστάσεις χρήσιμες για την εκεί λατρεία των όποιων πιστών.

Ένα ναϊκό αρχιτεκτόνημα είναι μια σμικρογραφία του ουράνιου κόσμου και

συνεπώς οι διαστάσεις του, τα τμήματά του, οι ίδιες οι γραμμές του κι οι μετακύ

τους αναλογίες συμβολίζουν πλήθος μυστικων δεδομένων τα οποία μόνον οι μυημένοι

στον ψυχικό κόσμο μπορούν να εννοήσουν.

Αλλά πάνω απ’ όλα ένα ναϊκό αρχιτεκτόνημα είναι η μυστηριακή επίδρασή του

πάνω στους πιστούς ή στους επισκέπτες που το ερευνούν.

Αυτό είναι κατ’ εξοχήν εμφανές στην Αγία Σοφία στην Κωνσταντινούπολη.

Αφελείς κάθονται και συζητάνε με τις ώρες για το αν υπάρχουν υπόγειοι διάδρομοι

κάτω από το Ιουστινιάνειο μεγαλούργημα, για το αν αυτοί είναι ερμητικά

κλειστοί, για το αν απολήγουν σε άγνωστα μέρη και υπόγειες κοιλότητες με

ιδιαίτερη λειτουργικότητα, και ούτε τους περνάει από το μυαλό ότι οι ίδιες οι

βασικές αρχιτεκτονικές γραμμές του τελειότερου χριστιανικού αρχιτεκτονήματος

από μόνες τους φωνάζουν κορυφαίες ψυχικές, οντολογικές, κοσμολογικές κι

εσχατολογικές αλήθειες τις οποίες βεβαίως οι κουφοί δεν μπορούν να ακούσουν.

Το κάθε ναϊκό αρχιτεκτόνημα έχει τον χαρακτήρα του και το Τζαμί του Σάχη

έχει τον δικό του. Ο σημερινός επισκέπτης το βρίσκει στην κεντρική

αυτοκρατορική πλατεία του Ισφαχάν η οποία ονομάζεται Ναξ-ε Τζαχάν (میدان نقش جهان/ Naqsh-e Jahan), δηλαδή Εικόνα

του Κόσμου.

Καθισμένος στον εξώστη του αυτοκρατορικού περιπτέρου Αλί Καπού, ο κάθε

Σαφεβίδης σάχης, όταν βρισκόταν στην πρωτεύουσά του, απολάμβανε την κίνηση των

υπηκόων του και τις επισκέψεις των διακεκριμένων αλλοδαπών που αφήνονταν να

διέλθουν από κει.

Όπως καθόταν εκεί, στην άκρη της πλατείας στα δεξιά του βρισκόταν το

αυτοκρατορικό Τζαμί το οποίο χρειάστηκε 18=19 χρόνια για να ανεγερθεί. Αν και το τζαμί αυτό είναι το μεγαλύτερο

σαφεβιδικό αρχιτεκτονικό μεγαλούργημα, πέρασε ένας ολόκληρος αιώνας σαφεβιδικής

μοναρχίας για να αποφασιστεί η ανέγερσή του.

Στον μάταιο κόσμο στον οποίο ζούμε

απαιτείται και έντονος κρατικός ανταγωνισμός για να οικοδομηθούν εξαιρετικά

αρχιτεκτονήματα! Όταν οι Οθωμανοί άρχισαν να οικοδομούν απέναντι από την Αγία

Σοφία (που είχε μετατραπεί σε πλήρες τζαμί με μινμπάρ, μιχράμπ και μιναρέδες)

την δική τους αρχιτεκτονική ‘απάντηση’ στο μεγαλούργημα της Ρωμανίας, τότε κι

οι Σαφεβιδείς αποφάσισαν ότι δεν έπρεπε να αφήσουν τους Οθωμανούς αναπάντητους.

Άλλωστε, ανάμεσα Ιράν και Τουράν, υπήρχε

πάντοτε ομοφωνία για το εξής: ο κόσμος του Τουράν είναι ο κόσμος της ισχύος και

ο κόσμος του Ιράν είναι ο κόσμος του κάλλους. Κανένας δεν επικρατεί απόλυτα,

κανένας δεν μπορεί χωρίς τον άλλο, αλλά οι Ιρανοί είναι ‘λογικό’ να μην έχουν

την στρατιωτική δύναμη των Τουρανών κι οι Τουρανοί είναι ‘λογικό’ να μην έχουν

την αισθητική των Ιρανών.

Έτσι, οι τουρανικές κι οι τουρκικές (Turkic) γλώσσες ήταν πάντοτε οι γλώσσες των στρατών στην Ασία (Κίνα, Ινδία,

Κεντρική Ασία, Σιβηρία, Ιράν και Μέση Ανατολή), την Ευρώπη (Ούννοι, Τάταροι και

Οθωμανοί) και την Αφρική (Μαμελούκοι και Οθωμανοί).

Σήμερα ακόμη η επίσημη γλώσσα του Πακιστάν

και της Ινδίας είναι μια γλώσσα με εκτεταμένο τουρκικό λεξιλόγιο κι ονομάζεται

‘χίντι’ στην Ινδία και ‘ουρντού’ στο Πακιστάν. Η λέξη αυτή σημαίνει ‘στρατός’

(στα σημερινά τουρκικά: ordu). Από την άλλη,

τα φαρσί (περσικά) ήταν πάντοτε η γλώσσα της λογοτεχνίας και της ποίησης.

Δεν υπήρξε ούτε ένας Οθωμανός σουλτάνος που να μην ήξερε πολύ καλά περσικά.

Και οι Σαφεβιδείς σάχηδες, οι οποίοι ήταν Τουρκμένοι και όχι Πέρσες, μιλούσαν

τουρκμενικά στους αξιωματικούς τους, περσικά (φαρσί) στους αρχιτέκτονες και

στους διπλωμάτες τους, και αραβικά στους επιστήμονες και στους θεολόγους τους.

Καθώς έχω επισκεφθεί και την Πόλη, και την Σαμαρκάνδη, και το Ισφαχάν και

την Άγκρα, θα παρουσιάσω κάποιες απλές συγκρίσεις.

Το Τζαμί του Σάχη στο Ισφαχάν (εγκαινιασμένο το 1629) έχει 100 μ μήκος, 130

μ πλάτος, τρεις θόλους των οποίων ο υψηλότερος έχει 53 μ ύψος και διάμετρο 25

μ. Οι τέσσερις μιναρέδες έχουν 48 μ ύψος έκαστος.

Το Μπλέ Τζαμί της Σταμπούλ (επίσημα Τζαμί του Σουλτάνου Αχμέτ Α’ –

εγκαινιασμένο το 1616) έχει 73 μ μήκος, 65 μ πλάτος, ένα θόλο ύψους 43 μ και

διαμέτρου 23.5 μ. Οι έξι μιναρέδες του έχουν 64 μ ύψος έκαστος.

Η Αγία Σοφία (ανεγερμένη σε μόνον πέντε χρόνια κι εγκαινιασμένη το 537)

έχει 82 μ μήκος, 73 μ πλάτος. Ο θόλος της εκκλησίας έχει 55.5 μ ύψος και 31-32

μ διάμετρο (δεν είναι ολότελα κυκλικός). Οι οθωμανικοί μιναρέδες έχουν 60 μ

ύψος έκαστος.

Το μαυσωλείο Τατζ Μαχάλ κτίσθηκε στην διάρκεια 21 ετών (1632-1653) από τον

Μεγάλο Μογγόλο αυτοκράτορα Σαχ Τζαχάν ως τάφος της κυρίας συζύγου του. Έχει

μήκος και πλάτος 58.6 μ (τετραγωνικού σχήματος στην βάση του) και συνολικό ύψος

73 μ. Ο εξωτερικός θόλος έχει ύψος αψίδας 24.4 μ και διάμετρο 17.7 μ, και οι

τέσσερις μιναρέδες έχουν 43 μ ύψος ο καθένας. Ο εσωτερικός θόλος φθάνει τα 35 μ

ύψος.

Το μαυσωλείο του Ταμερλάνου (Gūr-i Amīr / Amir Temur maqbarasi / گورِ امیر)

στην Σαμαρκάνδη, ανεγερμένο σε μόλις ένα έτος, έχει θόλο με ύψος 30 μ, αλλά βέβαια

κτίσθηκε δυο αιώνες νωρίτερα, το 1403-4. Και η αψίδα της εισόδου (ιουάν) στη

θρησκευτική σχολή του Ουλούγ Μπεκ στο Ρετζιστάν της Σαμαρκάνδης φθάνει τα 32 μ

ύψος.

Βεβαίως τα αρχιτεκτονικά μεγαλουργήματα δεν συγκρίνονται με βάση τις

διαστάσεις τους κι αυτές έχουν αναφερθεί εδώ εντελώς πληροφοριακά.

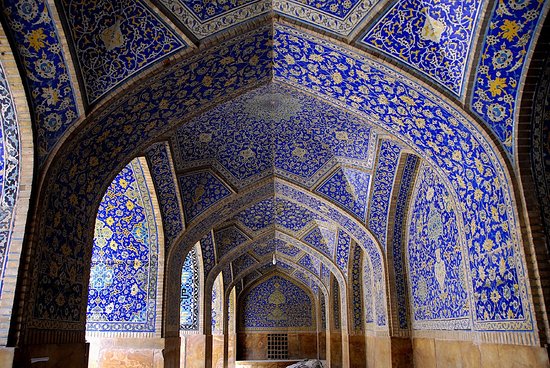

Στην περίπτωση του Τζαμιού του Σάχη στο Ισφαχάν, ο αυτοκρατορικός

αρχιτέκτονας Αλί Ακμπάρ Εσφαχανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ali_Akbar_Isfahani) είχε ένα

επιπλέον αρχιτεκτονικό πρόβλημα να λύσει: το τζαμί θα ανεγειρόταν σε μια άκρη

της αυτοκρατορικής πλατείας, η οποία ήταν ένας πολύ καλά και από αιώνες

πολεοδομημένος χώρος, και συνεπώς το τζαμί θα ερχόταν να προστεθεί σε μια σειρά

από ήδη υπαρκτά μνημεία (που σώζονται μέχρι σήμερα).

Αυτό εκ πρώτης όψεως δεν φαίνεται να είναι κάτι το δύσκολο, αλλά πρέπει

κανείς να λάβει υπόψει του το γεγονός ότι ένα τζαμί δεν ανεγείρεται οπουδήποτε,

αλλά πρέπει να είναι συμβατό με το μιχράμπ, μια εσοχή σε ένα από τους τοίχους

του τζαμιού που δείχνει την Κίμπλα, δηλαδή την κατεύθυνση προς την Μέκκα.

Αυτή την κατεύθυνση παίρνουν στις προσευχές τους οι μουσουλμάνοι και αυτό

το δεδομένο ορίζει πως κτίζεται ένα τζαμί. Ο αυτοκρατορικός αρχιτέκτονας έλυσε

το πρόβλημα προσθέτοντας ένα ελλειπτικό διάδρομο από την εξωτερική είσοδο (επί

της αυτοκρατορικής πλατείας) προς την εσωτερική πλατεία του τζαμιού το οποίο

σχεδιάστηκε σύμφωνα με την αρχή των τεσσάρων ιουάν (πυλώνες της εσωτερικής

πλατείας).

Όπως ήταν φυσικό σε κάθε τζαμί, διευθετήθηκαν και χώροι για τις εκεί

στεγαζόμενες θρησκευτικές σχολές που ήταν τότε το αντίστοιχο των σημερινών

πανεπιστημίων.

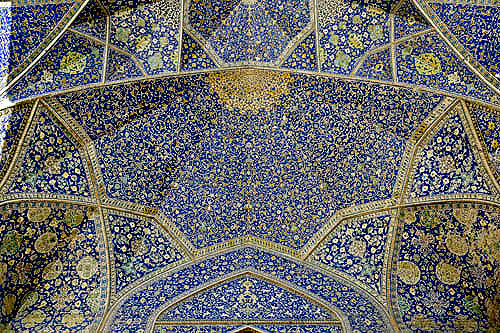

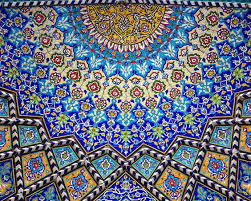

Η φυτική διακόσμηση των τοίχων του τζαμιού ακολούθησε την καλλιτεχνική

παράδοση χαφτ ρενγκ (των επτά χρωμάτων), ότι δηλαδή σε μια τεράστια επιφάνεια

που πρέπει να ζωγραφηθεί τα ταιριαστά μεταξύ τους χρώματα (συμπεριλαμβάνονται

και οι διαβαθμίσεις χρωμάτων) πρέπει να είναι επτά.

Έχω επισκεφθεί πολλές δεκάδες τζαμιά από

την Τουρκία και το Μαρόκο μέχρι την Υεμένη και την Ινδονησία. Εννοώ βέβαια

ιστορικά τζαμιά, γιατί δεν έχω λόγο να επισκεφθώ σύγχρονα τζαμιά. Το μόνο

σύγχρονο τζαμί στο οποίο έχω μπει ήταν το Τζαμί του Σεΐχη Ζαγιέντ στο Αμπού

Δάμπι, το οποίο είναι ένα νεοπλουτίστικο τζαμί όπου ξοδεύθηκαν πακτωλοί

χρημάτων για να αποκτήσουν τα Εμιράτα κι αυτά ένα τζαμί ‘αντάξιο’ (ο Θεός να το

κάνει!) εκείνων του Ιράν, του Ουζμπεκιστάν, της Τουρκίας, του Πακιστάν και της

Ινδίας.

Κανένα όμως τζαμί δεν με άφησε άφωνο όπως το Μαζτζίντ-ε Σαχ του Ισφαχάν. Οι

συνδυασμοί των χρωμάτων των φυτικών μοτίβων της διακόσμησης με έκαναν να νοιώσω

ότι βρισκόμουν μέσα σε ένα φωτεινό χώρο με πυκνή βλάστηση πολύ μακριά από μια

πόλη.

Σε όποιο σημείο και να βρισκόμουν, δεν αισθανόμουν ότι περπατούσα

(ξυπόλυτος εννοείται) μέσα σε ένα κτήριο.

Είχα περισσότερο την αίσθηση ότι περιπλανιόμουν σε ένα δάσος με πολύχρωμα

λουλούδια όπου κάποτε υπήρχε πολλή σκιά (στους πιο κλειστούς χώρους του

τζαμιού) και κάποτε επικρατούσε ένα σχεδόν εκτυφλωτικό φως.

Ήταν ένα πολύ πρωτόγνωρο συναίσθημα που δεν αισθάνθηκα ποτέ άλλοτε παρά

μόνον όταν ξανα-επισκέφθηκα αυτό το παράξενο τζαμί των ιδιαίτερων ακτινοβολιών.

Από τα παραπάνω γίνεται σαφές ότι, όταν βρέθηκα εκεί, τίποτα δεν μου έλεγε

ότι βρισκόμουν σε ένα τζαμί ή σε κάτι το σχετικό με το Ισλάμ. Βεβαίως σε ώρες

προσευχής δεν μπορείς να μπεις στους χώρους που διατίθενται για προσευχή. Τότε

ακούς και αραβικά. Αλλά αν προσέχεις τις αναπαραστάσεις των φυτικών μοτίβων, μπορεί

να νοιώσεις πιο απομονωμένος από όσο όταν είσαι μόνος σου στη μέση της ερήμου.

Άλλη παράξενη αίσθηση που είχα όταν βρισκόμουν εκεί είναι ότι νόμιζα ότι ο

ουρανός, τον οποίο έβλεπα όταν βρισκόμουν στην αυλή ή σε άλλα σημεία που το

επέτρεπαν, δεν είχε γαλανό χρώμα αλλά τυρκουάζ! Και στην ατμόσφαιρα ‘έβλεπα’

ότι διαχεόταν ένα έντονα φωτεινό κιτρινωπό χρώμα. Σταδιακά αλλά γρήγορα αυτές

οι (παρ)αισθήσεις χάθηκαν, όταν βγήκα από το τζαμί στην πλατεία.

Τυχεροί όσοι είδαν, όπως εγώ, πρώτα το Μπλε

Τζαμί της Πόλης και μετά το Τζαμί του Σάχη στο Ισφαχάν! Έχοντας δει το τζαμί

του Σουλτάνου Αχμέτ Α’, όταν μπαίνεις στο αυτοκρατορικό σαφεβιδικό τζαμί του

Ισφαχάν, καταλαβαίνεις ότι το ταξίδι τελείωσε κι έφθασες στον προορισμό σου.

Τόσο πολύ πιο ωραίο είναι ως απέραντοι

χρωματικοί συνδυασμοί που σε απορροφούν και σε στέλνουν σε ένα άλλο κόσμο. Δεν

είναι άσχημο το Μπλε Τζαμί. Κάθε άλλο! Είναι πολύ όμορφο. Είναι πιο όμορφο από

την Αγία Σοφία. Το μεγαλούργημα του Ιουστινιανού είναι ασύγρκιτα πιο

μεγαλοπρεπές. Αλλά είναι αυστηρό. Σου επιβάλλεται. Το Μπλε Τζαμί σε ξεκουράζει.

Υποθέτω ότι, αν θα υπήρχαν εξωγήινοι κι αν ένας από αυτούς έφθανε κατ’

ευθείαν στην Πόλη κι επισκεπτόταν την Αγία Σοφία και το Μπλε Τζαμί, αμέσως και

ανενδοίαστα θα έλεγε ότι το ‘κεντρικό’, το ‘αυτοκρατορικό’ μνημείο είναι η Αγία

Σοφία. Οι Οθωμανοί απέτυχαν να ξεπεράσουν τον Ιουστινιανό είτε στις διαστάσεις

του αρχιτεκτονήματος είτε στην αίσθηση που αναμεταδίδει. Αλλά το Μπλε Τζαμί

είναι πιο ωραίο. Όμως, όταν το δεις και μετά πας στο Ισφαχάν, καταλαβαίνεις ότι

έφθασες στο Κέντρο του Κάλλους.

Τα μνημειώδη τζαμιά, μαυσωλεία και θρησκευτικές σχολές της Σαμαρκάνδης

δίνουν ακριβώς την ιστορική διάσταση στην οποία τα κατατάσσει η εποχή τους:

όντας ανεγερμένα 200 χρόνια νωρίτερα, τα τουρανικά μνημεία της Σαμαρκάνδης

είναι δείγματα μιας τέχνης που ραφιναρίστηκε σε απαράμιλλο βαθμό δυο αιώνες

αργότερα στο Ισφαχάν.

Το εκπληκτικό Τατζ Μαχάλ στην Ακμπάρ Αμπάντ (σήμερα Άγκρα) είναι πολύ

διαφορετικό από το Τζαμί του Σάχη στο Ισφαχάν. Οι επιδράσεις της ιρανικής

ισλαμικής στην ισλαμική μογγολική τέχνη της Ινδίας είναι έντονες κι όλοι οι

ειδικοί τις αποδέχονται.

Αλλά το μαυσωλείο, όντας ανεγερμένο από μάρμαρο, είναι ένα αρχιτεκτονικό

μεγαλούργημα που κινείται στις διαβαθμίσεις του φωτός και της σκιάς πάνω στο

λευκό. Πολύ ωραίο, πολύ διαφορετικό και πολύ νεκρικό, μια και το λευκό

θεωρείται πένθιμο χρώμα.

Η μεγάλη του λιτότητα μετατρέπεται σε αυστηρότητα. Αλλά η επταχρωμία του

σαφεβιδικού αυτοκρατορικού τζαμιού αποπνέει την χαρά της ζωής και την ομορφιά

της φύσης.

Μου ήταν πάντοτε ένα μυστήριο το πως αισθάνθηκα μέσα στο τζαμί αυτό: σαν να

είχε ολότελα αλλάξει ο κόσμος. Αυτή την αίσθηση συνέχισα να φέρω πάντα μέσα

μου. Έτσι, όταν συνάντησα ένα Έλληνα μουσουλμάνο που είχε ζήσει στο Ιράν,

αμέσως μου ήρθε στο μυαλό η αίσθηση εκείνη και σκέφτηκα να ρωτήσω την γνώμη

του.

Πόσο μάλλον εφόσον ο φίλος κ. Μεγαλομμάτης είναι και ανατολιστής

ιρανολόγος. Θέλησα λοιπόν να δω αν η αίσθηση για το συγκεκριμένο τζαμί ήταν

μόνον δική μου και τον ρώτησα γενικά ποιο τζαμί από όλες τις χώρες όπου είχε

ζήσει ή ταξιδέψει του άρεσε περισσότερο. Η συζήτηση πρέπει να έγινε το 2014 ή

το 2015. Η απάντησή του με εξέπληξε επειδή ήταν ακαριαία:

– Φυσικά, το Τζαμί του Σάχη, στο Εσφαχάν!

Αμέσως μετά τον ρώτησα ‘γιατί’ και πήρα μια απίστευτη απάντηση:

– Είναι μια αναπαράσταση ειδώλου του Παραδείσου σε σμικρογραφία. Είναι σαν

να βλέπεις τον ίδιο τον Παράδεισο σε ένα καθρέπτη.

Στον κάθε καθρέπτη βλέπεις το αρνητικό είδωλο όντων κι αντικειμένων και στο

Τζαμί του Σάχη βλέπεις μια υλική εικόνα ενός σήμερα ανύπαρκτου αλλά μελλοντικά

υπαρκτού ιδεατού κόσμου.

Το Τζαμί του Σάχη είναι ένα μοναδικό μείγμα αιθέρα, γλυκών υδάτων και αέρα

με πολύ λίγη γη. Και ευτυχώς απουσιάζει ολότελα από αυτό η διαστροφή της

Θάλασσας.

Όταν μάλιστα περιέγραψα στον φίλο κ. Μεγαλομμάτη την περίεργη αίσθηση που

εγώ ως Χριστιανός έννοιωθα μέσα σε κείνο το τζαμί, εκείνος μου απάντησε ότι

αυτό ήταν πολύ φυσικό, επειδή οι προσλαμβάνουσες παραστάσεις μου, δηλαδή οι

εικόνες που οι διακοσμητικές αναπαραστάσεις φυτικών μοτίβων ανέδυαν,

προέρχονταν από ένα κόσμο στον οποίο δεν υπήρχε καμμία θρησκεία.

Ο φίλος ανατολιστής έκλεισε την συζήτηση ως εξής:

– Ποια ήταν η θρησκεία του Αδάμ στον Παράδεισο; Ποια είναι η θρησκεία των

πιστών του Θεού που αναφέρονται στα τελευταία κεφάλαια της Αποκάλυψης; Δεν

υπάρχει θρησκεία και στις δύο περιπτώσεις. Υπάρχει απόλυτη Πίστη. Έτσι όπως την

περιέγραψε ο Ιησούς: ως κόκκον σινάπεως.

Παραθέτω στην συνέχεια δυο βίντεο και μια σειρά από πληροφοριακά

αναγνώσματα για το Τζαμί του Σάχη. Στο τέλος υπάρχουν και επιπλέον σύνδεσμοι.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Исфахан: посещение столицы Сефевидов туркменских суфийских соперников османов

https://www.ok.ru/video/1442674969197

Esfahan: visiting

the capital of the Safavids, the Turkmen Sufi rivals of the Ottomans

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240259

Ισπαχάν: Περιήγηση στην πρωτεύουσα των Σαφεβιδών, των Μεγάλων Αντιπάλων των

Οθωμανών

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Τζαμί του Σάχη, Ισφαχάν – Shah Mosque, Isfahan – Мечеть Шаха, Исфахан – مسجد شاه اصفهان

https://www.ok.ru/video/1442764425837

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240260

=============================

Masjed-e Šāh

(Masjed-e Jadid-e ʿAbbāsi; renamed

Masjed-e Emām after the Revolution of 1978-79)

This mosque marked

the climax of building campaigns that transformed Isfahan into the new Safavid

capital city. Built between 1020/1611 and 1039/1630-31, the massive mosque

(some 19,000 square meters in area) was positioned at the southern end of the

Meydān-e Naqš-e Jahān. In terms of energizing urban spaces, the positioning of

the mosque at the southern end was calculated to ensure a steady flow of

traffic, for prayer, through the Meydān, thus helping to redirect business and

social life away from the Saljuq Meydān-e Kohna to this new urban center.

The mosque stood

directly across from the monumental royal Qay-ṣariya bazaar (for this bazaar see

Bakhtiar). Since it was intended to serve as the congregational mosque of the

new capital city, its placement formed a visual axis between two significant

facets of public life, commerce and religion. That these were further placed

under and braided with Safavid protection and patronage could not have been

missed for this longitudinal axis intersected with the latitudinal link between

the icons of imperial authority and justice, the ʿĀli Qāpu Palace on the

one hand, and of the personal piety and source of legitimacy of Safavid

kingship, embodied in the Shaikh Loṭf-Allāh Mosque on the other.

Masjed-e Šāh was

the first congregational mosque to have been built under Safavid royal

patronage. The complex theological-legal debates regarding the legitimacy of

the congregational Friday prayer during the occultation of the Twelfth Imam had

preoccupied Safavid clerical elite throughout the 16th century. The resolution

of this debate depended principally on the recognition of the concurrence of

kingship and justice under the umbrella of legalistic Twelver Shiʿite doctrine.

The vigorous legal

arguments and support of such scholars as Shaikh Loṭf-Allāh and Shaikh Bahāʾ-al-Din ʿĀmeli helped to

settle the thorny question of legitimacy in favor of the Safavids and hence

paved the way for the reinstitution of the Friday congregational prayer. Far

from a deliberate affront to the socio-religious centrality of the Masjed-e

Jāmeʿ, the venerable old

Saljuq congregational mosque of the city, the urban plan of the new imperial

capital city incorporated into its chief monuments the Masjed-e Šāh, a new

congregational mosque to mark the Safavid authority to sponsor legitimate

performance of this crucial religious obligation of Shiʿite community.

From the

architectural viewpoint, the mosque represents a classic Persian four-ayvān

plan with a domed chamber over the meḥrāb sanctuary. In many ways, however, this building represents an

exceptionally creative response to a series of pressing needs and preexisting

urban constraints. As in the case of the Shaikh Loṭf-Allāh Mosque, the

principal façade of the Masjed-e Šāh had to remain

flush with the southern side of the Meydān, while at the

same time orientating its meḥrāb(s) correctly toward Mecca.

Unlike the

compacted chapel-mosque, however, this requirement must have posed a difficult

challenge for the visual effect of the skewed internal axis, which would be

magnified considerably in the royal Masjed-e Šāh. The architects and patrons of

the mosque exploited this very potential for theatrical visual impact by

creating a crescendo of forms heaped from one side to the other; viewed from a

distance in the Meydān, as would have been the case for most denizens busy in

the public square, the eye of the beholder is lead from the open-armed portal

composition with its massive pištāq and soaring goldasta minarets to

increasingly volumetric and loftier units culminating with the pišṭāq-dome-minarets of

the qebla wall.

To the worshipper

entering the mosque, the transition from the gorgeously tiled and

moqarnas-covered ayvān on the Meydān side to the courtyard is mediated through

a twisted passageway-cum-ayvān that serves also as the northern ayvān of the

courtyard. This entrance complex corrects the alignment of the mosque by

twisting the axis of approach, but it also provides a liminal space passage

through which provides the worshipper the opportunity, visually and spatially

mediated, to leave the mundane world behind before entering the sanctified

space of the mosque.

An overwhelming

palette of turquoise-blue tiles covers all the surfaces inside and outside

(except what would be the “back” of walls, vaults, etc.). Nearly all the vast

surfaces of this mosque are decorated in the haft rangi (seven-color)

technique, the most economically feasible method of decoration favored in

17th-century Isfahan. Other notable features of the mosque are its two

extraordinarily tall pulpits (menbar), one open for good weather and another

covered for bad weather.

The meḥrāb, soaring at ten

feet, and measuring three feet in width, is made of marble crowned with a

gold-encrusted cupboard holding a Qurʾan believed to have been copied by Imam ʿAli al-Reżā as well as the

bloodstained robe of Imam Ḥosayn (Chardin, VII, pp. 343-44, 353; Blake, p. 143). Such

symbolically charged relics of the Imams further emblazon the legitimacy of the

Twelver Shiʿite practice of

Safavid kingship embodied in the very conceptualization and construction of

this first congregational mosque of the Safavids.

The other

extraordinary architectural aspect of this mosque is its integration of a

madrasa into the fabric of the mosque (Honarfar, 1965, pp. 454-57). Two

courtyards with adjoining chambers flank the qebla sanctuary, the massive domed

chamber and its adjacent vaulted prayer halls. While awaiting further research

on the mosque in general and the madrasa in particular, it may be postulated

here that the incorporation of the madrasa into this first Safavid imperial

congregational mosque was prescribed as another indication of the choice of

Isfahan as not only the political capital, but also, and perhaps with more

significance, as an imperial capital of Twelver Shiʿism.

As the inscribed

chronogram, in the poetic decoration on the silver doors, added by Shah Ṣafi I in 1046/1636-37, would

indicate, with this mosque the doors of Kaʿba were opened in Isfahan (šod dar-e Kaʿba dar Ṣefāhān bāz, which is

apparently on the model of the earlier chronogram “kaʿba-ye ṯāni banā šoda” on the beginning

of the construction in 1020/1611; Mollā Jalāl-al-Din, p. 412; Honarfar, 1965,

pp. 433-34), and, as such, Isfahan would stand in rivalry to Constantinople/Istanbul,

as Safavid Shiʿite kingship would

to Ottoman Sunni caliphate.

The complex

enunciations of this braided iconography of kingship, religion and polity, are

found throughout the extensive epigraphic program of the Masjed-e Šāh. The

principal foundation inscription across the portal was designed by the famous

calligrapher ʿAli-Reżā ʿAbbāsi (Honarfar, 1965,

pp. 428-29; see Plate XI [3]). It states that Shah ʿAbbās funded the

project from the royal treasures (ḵāleṣa) for the spiritual

benefit of his grandfather Shah Ṭahmāsb, thus linking through this imperial icon of Twelver Shiʿite legitimacy and through the

outpouring of the generosity of the Safavid household the two illustrious

reigns.

An addendum to this

inscription, written by Moḥammad-Reżā Emāmi, credits Moḥebb-ʿAli Beg Lala, the

trainer of the ḡolāms and chief

supervisor of imperial buildings, with the supervision over the construction.

This same dignitary of the household had joined the Shah by contributing to the

endowments of the mosque (waqf) a considerable thirty percent of the entire

endowment from his personal funds (Honarfar, 1965, pp. 429-30; Babaie, 2004, p.

91).

The names of two

architects are also associated with this mosque: Ostād ʿAli-Akbar Beg Eṣfahāni as the mosque’s engineer

(mohandes) and architect, whose name appears in the same inscription as that of

the royal supervisor, and Ostād Badiʿ-al-Zamān Tuni Yazdi, whose job was to procure the land and

construction resources (Mollā Jalāl-al-Din, p. 412;

McChesney, pp. 121-22).

Several traditions,

recorded in contemporary chronicles, spin the story of the difficult task of

acquiring the land from an unwilling owner and the miraculous discovery of

marbles for the construction into evidence for the protected sanctity of this

endeavor by ShahʿAbbās the Great, whose

authority was considered to be based on justice and sanctioned according to

legal Twelver Shiʿite precepts. In

fact, the entire epigraphic program of the mosque, designed by the most famous

calligraphers of the first half of the 17th century, utilize Qurʾanic passages and eulogies to the

family of the Prophet Moḥammad and Imam ʿAli b. Abi Ṭāleb to affix onto

the surfaces of the mosque the enunciations of the legitimacy of the formation

of kingship and hence congregational prayer under the Safavids in this new

imperial capital.

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/isfahan-x3-mosques

==============================

Masjid-i Imam

Isfahan

The Masjid-i Imam,

formerly known as Masjid-i Shah, was built on the south side of Isfahan’s

maydan, the royal square of Isfahan, that had been built under Shah ‘Abbas.

‘Abbas moved the capital of the Safavid dynasty to Isfahan in 1597 with the

goal of centering political, religious, economic, and cultural activities, in

the process shifting Isfahan’s center away from the area surrounding the old

Friday mosque in the north and relocating it closer to the Zayandeh river. The

Masjid-i Shah was Shah ‘Abbas’s largest architectural monument. The mosque’s

monumental portal iwan is located exactly opposite the portal iwan on the

northern arcade of the maydan, which connects the maydan to the old bazaar to

the north.

Construction of the

Masjid-i Shah began in 1611 under Shah ‘Abbas, and was completed around 1630

during the rule of Shah Safi, ‘Abbas’s successor, who ruled from 1629 to 1642.

Later, in 1638, marble dadoes were added to the structure. Much is known about

the people who were involved in the mosque’s construction from the inscriptions

installed on the building, which identify Badi’ al-Zaman Tuni as responsible

for the building plans and site arrangement, ‘Ali Akbar Isfahani as the

engineer, and Muhibb ‘Ali Beg as the general contractor.

From the center of

the southern wall of the maydan, one enters the mosque through a recessed

vestibule where the main portal to the mosque is located on the vestibule’s

southern wall. This area connects on its two other sides (east and west) to the

maydan’s corridor, which runs behind its mercantile facilities. Only the

vestibule follows the maydan’s orientation (north-south). The rest of the

mosque, rectangular in shape (100 by 130 meters), is rotated 45 degrees to

orient it toward Mecca, according to which the qibla wall is installed.

To achieve this

orientation toward Mecca the main portal is connected to a triangular

vestibule, which connects it to the mosque’s courtyard via the space behind the

northeast iwan.

Following the

Iranian traditional mosque plan, the Masjid-i Shah has a court (50 by 67

meters) surrounded by a two-story arcade on four sides with four iwans, one at

the center of each side, and a domed sanctuary behind the southwest iwan,

oriented towards Mecca. However, the mosque’s plan presents an interesting

variation: behind each lateral iwan (on the northwest and southeast) is a domed

chamber. The domed sanctuary behind the southwest iwan is flanked by

rectangular rooms (36 meters by 18 meters each) functioning as winter prayer

halls that are entered from the domed sanctuary aligned on the

northeast-southwest axis.

These halls are

covered by eight domes and connect to two rectangular arcaded courts serving as

madrasas (22 by 44 meters each) also aligned on the northeast-southwest axis

and are only accessed from the domed chambers behind the southeast and

northwest iwans, respectively. Both the main portal iwan, overlooking the

maydan, and the sanctuary iwan are flanked by a pair of soaring cylindrical

minarets 34 meters in height. These minarets are decorated with tile mosaics of

epigraphic elements (“no God but God”). On top of its upper zone runs an

inscription band in white on a blue background, marking the beginning of three

tiers of muqanas units, each unit outlined with yellow lines and inscribing a

floral arabesque mainly in blue. These muqarnas appear to hold the minaret’s

roofed balcony, which wraps around a cylindrical core narrower than the lower

shaft of the minaret.

The prelude to the

mosque, the main portal iwan located on the south arcade of the maydan, was

finished in 1616, prior to the rest of the building, so that it could complete

the southern facade of the maydan. The portal was covered with tile mosaic

above a continuous marble dado, and achieved an extraordinary monumentality

through its immense scale, as its arch rises almost twenty-eight meters. It is

framed by an inscription band of white thuluth script with a dark blue

background. The arch is ornamented with a turquoise triple-cable frame

springing from a vase-like marble base (pedestal).

The main portal

iwan is surmounted by tiers of muqarnas forming a semi-dome. Two large tiled

panels, resembling a prayer carpet, flank the main door, above which an

inscription band, also in white script on a dark blue background, identifies

Ali Reza as the calligrapher, 1616 as the year of the execution, and the name

of the patron Shah ‘Abbas in the center in light blue.

In the court, the

iwan preceding the domed sanctuary is larger than the other three iwans at the

centers of the two-story arcades. The dome of the sanctuary is vast in scale

(25 meters across by 52 meters high), and, like most Timurid prototypes,

comprises two shells, the bulbous dome being fourteen meters higher than the

interior dome. On the exterior, the bulbous dome is covered with a spiraling

beige arabesque on a light blue background.

The dome rises on a

high drum and a sixteen-sided transitional zone. The interior of the dome is

ornamented with a sunburst at the apex from which descend tiers of arabesque. The

eight domes in each of the prayer halls adjacent to the domed sanctuary are

decorated with mosaic tilework of concentric medallions in floral motifs.

The arches on which

these domes rest ascend from undecorated octagonal columns that divide the

space of these halls into eight bays.

The mosque’s

interior and exterior walls are fully covered with a polychrome, mostly dark

blue, glazed tile revetment above a continuous marble dado. Throughout the

whole mosque, with the exception of the sanctuary dome and portal iwan, Shah

‘Abbas was keen to minimize labor costs and time by introducing a novel

technique called “haft-rangi” (seven colors). Instead of the Timurid and early

Safavid tile mosaic, in which each tile piece was cut in a different shape to

fit its designated place, the haft-rangi is usually a square tile that

incorporates various colors in one firing.

This technique,

aesthetically less complex than mosaic tile technique, economical, and fast,

was juxtaposed to the mosaic tile technique. It glitters in the sun to

magnificent effect, but is ill-suited to dark spaces, such as the sanctuary.

Most of the tilework was replaced in the 1930s based on the revetment that

remained in situ. Water is an important element in the design; both the main

court and the courts of the madrasas have pools at their center reflecting the

architectural splendor of the Masjid-i Shah.

Sources:

Blair, Sheila S.

and Jonathan M. Bloom. The Art and Architecture of Islam. New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1994. 188-190

Blunt, Wilfrid.

Isfahan: Pearl of Asia. London: Elek Books, 1966. 77-84

Michell, George.

Architecture of the Islamic World. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978. 253-4

Pope, Arthur Upham.

Persian Architecture: The Triumph of Form and Color. New York: George

Braziller, 1965. 207f

Pourjavady, N.

(ed.), E. Booth-Clibborn (originator). The Splendour of Iran. London:

Booth-Clibborn Editions, 2001. 100-101, 147.

https://archnet.org/sites/1622

=======================

Imam Mosque

The mosque is one

of the treasures featured on Around the World in 80 Treasures presented by the

architecture historian Dan Cruickshank.

Monday, April 5,

2010

Imam Mosque

(Masjid-e Jam ‘e Abbasi), also called Masjid-e Shah (Royal Mosque) before the

victory of Islamic Revolution, is one of the finest and the most stunning

buildings in the world standing in south side of Naghsh-i Jahan Square

(Isfahan).

The Mosque, begun

in 1612 during the reign of Shah Abbas I represents the culmination of a

thousand years of mosque building and a magnificent example of architecture,

stone carving, and tile work in Iran, with a majesty and splendor that places

it among the world’s greatest buildings. The Mosque is also an excellent example

of Islamic architecture of Iran, and regarded as the masterpiece of Persian

Architecture. It is registered along with the Naghsh-i Jahan Square as a UNESCO

World Heritage Site. Its construction began in 1611, and its splendor is mainly

due to the beauty of its seven-color mosaic tiles and calligraphic

inscriptions.

The port of the

mosque measures 27 m (89 ft) high, crowned with two minarets 42 m (138 ft)

tall. The Mosque is surrounded with four iwans and arcades. All the walls are

ornamented with seven-color mosaic tile.

The most

magnificent iwan of the mosque is the one facing the Qibla measuring 33 m (108

ft) high. Behind this iwan is a space which is roofed with the largest dome in

the city at 52 m (171 ft) height. The dome is double layered.

The acoustic

properties and reflections at the central point under the dome is an amusing

interest for many visitors. There are two seminaries at the southwest and

southeast sections of the mosque.

The portal, almost

a building in itself and understood as an aspect of the Maidan rather than of

the mosque, forms a welcoming embrace, inviting and guiding the throngs outside

into the refuge, security and the renewal the mosque provides. In fact, it is the

most thrilling example of human artifice that could be imagined. Its height

amounts to 30 m, the flanking minarets are 42 m tall- with the sanctuary

minarets higher still, 48 m. The two panels which flank the actual entrance

within the recess carry the design of a prayer rug, a reminder of the mosque’s

essential purpose.

A mosaic tile

inscription by Ali Reza Abbasi can be seen on the main portal of the mosque,

which is dated 1616 AD (completion date of the portal). Below this, there is

still another inscription that gives the name of the builder as Ali Akbar

Esfahani, and that of the construction supervisor as Muhib Ali Beigallah.

Several other inscriptions can also be seen on the portal and in the narthex of

the mosque.

However, Shah Abbas

needed a showplace, just as he needed the Sheikh Lutfollah Mosque for private

meditation, and he built this whole gigantic structure, with two seminaries

(madrasahs) in the few years from 1612 until his death in 1629, the year of the

great copula’s completion.

Through the outer

portal one enters a noble vestibule, which is a usual feature. Octagonal, it

has no particular direction; it can therefore serve as a pivot on which the

axis of the building is turned, the gateway to another world of splendor and

concentrated power.

Of the

classical-Jour ivans the west ivan has a wide porch surmounted by a minaret.

The south ivan (also the largest) opens to reveal a great prayer hall

surmounted by a double cupola 38 m high on the inside and 52 m on the outside

(leaving a 12-meter empty space which serves as an extraordinary “echo

chamber”, since a speaker in the mehrab can be distinctly heard in all other

parts of the mosque), its surface decoration being of the most sumptuous

richness, a floral design in gold, yellow and white spiraling on a deep blue

ground. In the center of the great prayer hall look out for a few black paying

stones underneath the dome, which when stamped upon create seven clear echoes.

Try it for yourself; everyone else does.

The fact that sound

is equally carried to all parts of the dome chamber and cloisters on each side

as well as to the courtyard and the lateral porches indicates that four

centuries ago, Iranian architects were able to produce buildings provided with

acoustics not inferior to those of any modern building.

Great jasper and

marble bowls like fonts each made of a solid stone block, can be seen near the

portal gate, under the western and eastern domes, and in the cloisters on both

sides of the great southern prayer hall. These are unique in terms of delicacy

and care with which they were made. They used to be filled, on various with

water 91 sherbet to quench the thirst of worshipping throngs in summer.

To the east and

west of the mosque there are two madrasehs (theological colleges). Two long

seminaries at the back are suitably studious in their architectural

tranquillity. The dome, elegant and sensitive in contour, slightly bulbous, set

on a high drum, is simple, of remarkably clean and expressive outline

uncluttered by any supplementary constructions. In the school building to the

southwest of the courtyard there is a piece of stone which acts as a sundial

attributed to Sheikh Bahai, the famous scientist and mathematician of the

period of Shah Abbas. It indicates noon in Esfahan throughout the year.

The Seljuqs and the

Safavids found the Shah Mosque as a channel through which they could express

themselves with their numerous architectural techniques. The four- iwan format,

finalized by the Seljuq dynasty, firmly established the courtyard facade of

such mosques as more important than their exterior ones. During the Seljuq

rule, as Islamic mysticism was on the rise in the region, the four-iwan

arrangement came to be interpreted as seeking true meaning within the

appearance. Their presence can serve the sole purpose of being the passageway

between the material world and that of the spiritual. It must also be noted

that glazed brickwork and tiling had little appeal to the Seljuqs as they

primarily favored the distinct tranquil color of turquoise blue.

Facing northwards,

the mosque’s portal to the Maidan is usually under shadow but since it has been

coated with radiant tile mosaics it glitters with a predominantly blue light of

extraordinary intensity. The ornamentation of the structures is utterly

traditional, as it recaptures the classic Iranian motifs of symbolic appeal for

fruitfulness and effectiveness. Within the symmetrical arcades and the balanced

iwans, one is drowned by the endless waves of intricate arabesque in golden

yellow and dark blue which bless the spectator with a space of internal

serenity.

Covered with

premeditated calligraphic fresco, the front doors are used as an apparatus to

remind the spectator of the glory of God and of Shah Abbas I himself. Entering

from the northern iwan, the compelling physical presence of the identical side

iwans direct our attention to the soaring qibla iwan situated straight ahead.

As a result such architecture stresses the degree of fidelity in the structure

which makes it explicitly pervasive.

According to A U

Pope, both the ground plan and the structure of the building reflect the

doctrinal simplicity of Islam. Circulation and communication are everywhere

facilitated, nowhere impeded. The common floor level is at no place broken by

steps, railings or screens. The walls merge into their garden-Iike floriation

or open onto real and natural gardens. Because of the concentration of the

bearing load on octagonal stone columns, wide vistas open up and voids are at

maximum. The ornamentation is wholly traditional, repeating the Iranian motif

of appeal for fertility and abundance. Almost the entire surface of the

building is covered with enamel tile. A vast display of floral wealth, abstract

and imaginative, emphasizes the Persian poetic passion for flowers, as well as

the appeal for a continuance of an abundant life. The best time to photograph

is about II am when the sun is overhead.

http://www.iranreview.org/content/Documents/Imam_Mosque.htm

=====================================

Meidan Emam,

Esfahan

Built by Shah Abbas

I the Great at the beginning of the 17th century, and bordered on all sides by

monumental buildings linked by a series of two-storeyed arcades, the site is

known for the Royal Mosque, the Mosque of Sheykh Lotfollah, the magnificent

Portico of Qaysariyyeh and the 15th-century Timurid palace. They are an

impressive testimony to the level of social and cultural life in Persia during

the Safavid era.

Outstanding

Universal Value

Brief Synthesis

The Meidan

Emam is a public urban square in the centre of Esfahan, a city located on the

main north-south and east-west routes crossing central Iran. It is one of the

largest city squares in the world and an outstanding example of Iranian and

Islamic architecture. Built by the Safavid shah Abbas I in the early 17th

century, the square is bordered by two-storey arcades and anchored on each side

by four magnificent buildings: to the east, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque; to the

west, the pavilion of Ali Qapu; to the north, the portico of Qeyssariyeh; and

to the south, the celebrated Royal Mosque. A homogenous urban ensemble built

according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan, the Meidan Emam was the

heart of the Safavid capital and is an exceptional urban realisation.

Also known as

Naghsh-e Jahan (“Image of the World”), and formerly as Meidan-e Shah, Meidan

Emam is not typical of urban ensembles in Iran, where cities are usually

tightly laid out without sizeable open spaces. Esfahan’s public square, by

contrast, is immense: 560 m long by 160 m wide, it covers almost 9 ha. All of

the architectural elements that delineate the square, including its arcades of

shops, are aesthetically remarkable, adorned with a profusion of enamelled

ceramic tiles and paintings.

Of particular

interest is the Royal Mosque (Masjed-e Shah), located on the south side of the

square and angled to face Mecca. It remains the most celebrated example of the

colourful architecture which reached its high point in Iran under the Safavid

dynasty (1501-1722; 1729-1736). The pavilion of Ali Qapu on the west side forms

the monumental entrance to the palatial zone and to the royal gardens which

extend behind it. Its apartments, high portal, and covered terrace (tâlâr) are

renowned. The portico of Qeyssariyeh on the north side leads to the 2-km-long

Esfahan Bazaar, and the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque on the east side, built as a

private mosque for the royal court, is today considered one of the masterpieces

of Safavid architecture.

The Meidan Emam was

at the heart of the Safavid capital’s culture, economy, religion, social power,

government, and politics. Its vast sandy esplanade was used for celebrations,

promenades, and public executions, for playing polo and for assembling troops.

The arcades on all sides of the square housed hundreds of shops; above the

portico to the large Qeyssariyeh bazaar a balcony accommodated musicians giving

public concerts; the tâlâr of Ali Qapu was connected from behind to the throne

room, where the shah occasionally received ambassadors. In short, the royal

square of Esfahan was the preeminent monument of Persian socio-cultural life

during the Safavid dynasty.

Criterion (i): The

Meidan Emam constitutes a homogenous urban ensemble, built over a short time

span according to a unique, coherent, and harmonious plan. All the monuments

facing the square are aesthetically remarkable. Of particular interest is the

Royal Mosque, which is connected to the south side of the square by means of an

immense, deep entrance portal with angled corners and topped with a half-dome,

covered on its interior with enamelled faience mosaics.

This portal, framed

by two minarets, is extended to the south by a formal gateway hall (iwan) that

leads at an angle to the courtyard, thereby connecting the mosque, which in

keeping with tradition is oriented northeast/southwest (towards Mecca), to the

square’s ensemble, which is oriented north/south.

The Royal Mosque of

Esfahan remains the most famous example of the colourful architecture which

reached its high point in Iran under the Safavid dynasty. The pavilion of Ali

Qapu forms the monumental entrance to the palatial zone and to the royal

gardens which extend behind it. Its apartments, completely decorated with

paintings and largely open to the outside, are renowned.

On the square is

its high portal (48 metres) flanked by several storeys of rooms and surmounted

by a terrace (tâlâr) shaded by a practical roof resting on 18 thin wooden

columns. All of the architectural elements of the Meidan Imam, including the

arcades, are adorned with a profusion of enamelled ceramic tiles and with

paintings, where floral ornamentation is dominant – flowering trees, vases,

bouquets, etc. – without prejudice to the figurative compositions in the style

of Riza-i Abbasi, who was head of the school of painting at Esfahan during the

reign of Shah Abbas and was celebrated both inside and outside Persia.

Criterion (v): The

royal square of Esfahan is an exceptional urban realisation in Iran, where

cities are usually tightly laid out without open spaces, except for the

courtyards of the caravanserais (roadside inns). This is an example of a form

of urban architecture that is inherently vulnerable.

Criterion (vi): The

Meidan Imam was the heart of the Safavid capital. Its vast sandy esplanade was

used for promenades, for assembling troops, for playing polo, for celebrations,

and for public executions. The arcades on all sides housed shops; above the portico

to the large Qeyssariyeh bazaar a balcony accommodated musicians giving public

concerts; the tâlâr of Ali Qapu was connected from behind to the throne room,

where the shah occasionally received ambassadors. In short, the royal square of

Esfahan was the preeminent monument of Persian socio-cultural life during the

Safavid dynasty (1501-1722; 1729-1736).

Integrity

Within the

boundaries of the property are located all the elements and components

necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the property,

including, among others, the public urban square and the two-storey arcades

that delineate it, the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque, the pavilion of Ali Qapu, the

portico of Qeyssariyeh, and the Royal Mosque. Threats to the integrity of the

property include economic development, which is giving rise to pressures to

allow the construction of multi-storey commercial and parking buildings in the

historic centre within the buffer zone; road widening schemes, which threaten

the boundaries of the property; the increasing number of tourists; and fire.

Authenticity

The historical

monuments at Meidan Emam, Esfahan, are authentic in terms of their forms and

design, materials and substance, locations and setting, and spirit. The surface

of the public urban square, once covered with sand, is now paved with stone. A

pond was placed at the centre of the square, lawns were installed in the 1990s,

and two entrances were added to the northeastern and western ranges of the

square. These and future renovations, undertaken by Cultural Heritage experts,

nonetheless employ domestic knowledge and technology in the direction of

maintaining the authenticity of the property.

Management and

Protection requirements

Meidan Emam,

Esfahan, which is public property, was registered in the national list of

Iranian monuments as item no. 102 on 5 January 1932, in accordance with the

National Heritage Protection Law (1930, updated 1998) and the Iranian Law on

the Conservation of National Monuments (1982). Also registered individually are

the Royal Mosque (Masjed-e Shah) (no. 107), Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque (no. 105),

Ali Qapu pavilion (no. 104), and Qeyssariyeh portico (no. 103).

The inscribed World

Heritage property, which is owned by the Government of Iran, and its buffer

zone are administered and supervised by the Iranian Cultural Heritage,

Handicrafts and Tourism Organization (which is administered and funded by the

Government of Iran), through its Esfahan office. The square enclosure belongs

to the municipality; the bazaars around the square and the shops in the

square’s environs are owned by the Endowments Office. There is a comprehensive

municipal plan, but no Management Plan for the property. Financial resources

(which are recognised as being inadequate) are provided through national,

provincial, and municipal budgets and private individuals.

Sustaining the

Outstanding Universal Value of the property over time will require developing,

approving, and implementing a Management Plan for the property, in consultation

with all stakeholders, that defines a strategic vision for the property and its

buffer zone, considers infrastructure needs, and sets out a process to assess

and control major development projects, with the objective of ensuring that the

property does not suffer from adverse effects of development.

http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/115

========================

Περισσότερα:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shah_Mosque_(Isfahan)

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Мечеть_Имама

https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Τζαμί_του_Σάχη

https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/مسجد_شاه_(اصفهان)

Συγκρίσιμα μνημεία

Στο Εσφαχάν:

Το Σελτζουκικό Μεγάλο Τζαμί της Παρασκευής:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jameh_Mosque_of_Isfahan

Στην Τουρανική Αυτοκρατορία (Σαμαρκάνδη) των απογόνων του Ταμερλάνου, στην

Οθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία (Σταμπούλ) και στην Μογγολική Αυτοκρατορία των

Γκορκανιάν (Ινδία – Άγκρα / Αμπάς Αμπάντ και Σαχ Τζαχάν Αμπάντ / Παλαιό Δελχί):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Registan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulugh_Beg_Madrasa,_Samarkand

(Θρησκευτικές σχολές Ulugh Beg Madrasah, Tilya-Kori Madrasah, Sher-Dor Madrasah)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gur-e-Amir

(Ταφικό Μνημείο του Ταμερλάνου)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bibi-Khanym_Mosque

(Ταφικό Μνημείο της κύριας συζύγου του Ταμερλάνου)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sultan_Ahmed_Mosque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagia_Sophia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taj_Mahal

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humayun%27s_Tomb

Σχετικά με το Ισπαχάν:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isfahan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sheikh_Lotfollah_Mosque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%80l%C4%AB_Q%C4%81p%C5%AB

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chehel_Sotoun

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasht_Behesht

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Safavid_dynasty

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Исфахан

https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ισφαχάν

Γενικώτερα για το Σαφεβιδικό Ιράν:

Δυναστεία Σαφεβιδών (1501-1736): οι Σούφι Σάχηδες και Τρομεροί Αντίπαλοι

των Οθωμανών ήταν Τουρκμένοι – όχι Πέρσες!

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/07/20/δυναστεία-σαφεβιδών-1501-1736-οι-σούφι-σάχηδ/

No comments:

Post a Comment