ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 5η Σεπτεμβρίου 2019.

Στο κείμενό του αυτό, ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης συνεχίζει την παρουσίαση στοιχείων από διάλεξη την οποία είχα δώσει τον Ιανουάριο του 2019 στην Νουρσουλτάν (πρώην Αστανά), εστιάζει την περιγραφή του στους Κασκάι Κιζιλμπάσηδες του Ιράν, και μνημονεύει συνεχώς συμπεράσματα, τα οποία είχα από καιρού συναγάγει και καταστήσει δημόσια στην διάλεξή μου εκείνη.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — —

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/05/τουρκία-ιράν-κιζιλμπάσηδες-κασκάι-υπ/

===========

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής — Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Πολλοί με ρωτούν επίμονα, εξαιτίας της δημοσίευσης των τελευταίων δύο-τριών κειμένων μου περί Κιζιλμπάσηδων, αν η αναζωπύρωση του κιζιλμπασικού κινήματος στην Τουρκία τα τελευταία δέκα χρόνια είναι υπόθεση που σχετίζεται με ιρανικό δάκτυλο ή με τον Φετουλάχ Γκιουλέν, εξόριστο αρχηγό του Χιζμέτ (: ‘Υπηρεσία’), ενός παράνομου κυκλώματος χρηματοδοτημένου από την Μοσάντ του Ισραήλ και την ΣΙΑ των ΗΠΑ.

Οι άγνωστοι στον περισσότερο κόσμο Κασκάι του Ιράν: η τουρκμενική φυλή που παραδοσιακά συμμετείχε στο κιζιλμπασικό κίνημα

Οι ερωτήσεις αυτές δείχνουν σε ποιο βαθμό επηρεάζει σήμερα η επίσημη παραπληροφόρηση κι αποπληροφόρηση που γίνεται ασταμάτητα και για δεκαετίες από τα ΜΜΕ.

Α. Πως μαθαίνει Κάποιος την Αλήθεια

Αν κάποιος δαπανούσε 5–6 μήνες στο Ιράν κι άλλους τόσους στην Τουρκία, θα καταλάβαινε πολύ καλά την κατάσταση, αν είχε την οξυδέρκεια να μην διαβάζει τις διεθνείς και τις τοπικές εφημερίδες, να μην βλέπει τα εκεί και αλλού τηλεοπτικά κανάλια, να μη διαβάσει κανένα σχετικό βιβλίο ή άρθρο στο Ιντερνέτ, και να ξεκινήσει την έρευνά του πηγαίνοντας πάντοτε στον μόνιμα σωστό τόπο: στα χωριά (ενδεχομένως έχοντας μαζί του κι ένα καλό μεταφραστή).

Έπειτα, μετά από μια αρχική περιοδεία, θα έπρεπε να διαβάσει πολύ — τοπικό και διεθνή τύπο και εκλαϊκευτική επιστημονική βιβλιογραφία. Κάνοντας αυτό, αμέσως θα εύρισκε πολλά σημεία που θα έρχονταν σε ευθεία αντίθεση με την αλήθεια που θα είχε ήδη κατά τόπους δει.

Οπότε, για να ολοκληρώσει, θα έπρεπε να ξαναπάει στους τόπους, όπου θα είχε ήδη γνωριστεί με απλούς ντόπιους ανθρώπους και να τους ρωτήσει για τα σημεία αυτά όπου θα είχε εντοπίσει διαφορές. Τότε θα έπαιρνε και το πρώτο μεγάλο σοκ της ζωής του γιατί οι ντόπιοι αυτοί πληθυσμοί — χωρίς σπουδές σε πανεπιστήμια αλλά με οξυδέρκεια, σωστή κρίση, ηθικές αρχές, ικανότητα αντίληψης, και επιπλέον με μια απίθανη και τεράστια προφορική παράδοση που για να καταγραφεί θα χρειάζονταν εγκυκλοπαίδειες — θα του έλεγαν

α. και γιατί τα όσα παραμορφωτικά της αλήθειας είχε διαβάσει είναι λάθος, και ακόμη πιο κρίσιμα,

β. που και σε ποιον χρησιμεύει ένα τέτοιο λάθος ή ψέμμα.

Γι’ αυτό κάνω αναφορά σε ταξίδι 5–6 μηνών σε μια χώρα.

Έχω ταξιδεύσει στο Ιράν κι έχω πάει σε κάποιες επαρχίες. αλλά δεν έχω κάνει την προαναφερμένη έρευνα. Αλλά έχω γνωρίσει από κοντά τον Έλληνα ανατολιστή, ιστορικό και πολιτικό επιστήμονα, καθ. Μουχάμαντ Σαμσαντίν Μεγαλομμάτη, ο οποίος έχει οργώσει όλες τις εκτάσεις από το Μαρόκο μέχρι την Κίνα κι από την Σιβηρία μέχρι την Μοζαμβίκη ερευνώντας τα πάντα — ακόμη και στα πιο μακρινά χωριά.

Αυτός είναι ο άνθρωπος που βρήκε, ενόσω ακόμη σπούδαζε σε μεταπτυχιακό και σε διδακτορικό επίπεδο πίσω στα τελη του 1970 και του 1980, τα λάθη και τα ψέμματα, τις παραποιήσεις, αλλοιώσεις και διαστροφές που δίδασκαν οι καθηγητές του ως τάχα ‘επιστημονική αλήθεια’ και κατάλαβε ότι τα όσα είχε μάθει θα έπρεπε να τα ελέγξει για να διαπιστώσει σε ποιο βαθμό είναι σωστά και σε ποιο βαθμό όχι.

Ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης δεν έχει βέβαια το αλάθητο (ούτε κι ο ίδιος άλλωστε πιστεύει κάτι τέτοιο) αλλά ντε φάκτο μετατρέπει τα άθλια ψευτο-καθηγητάκια που στραβώνουν τους φοιτητές στην Ελλάδα σε τιποτένιους, θλιβερούς νάνους και σε κοινούς, στυγνούς εγκληματίες που πληρώνονται από τον μέσο Έλληνα φορολογούμενο για να τον ταΐζουν τύφλα, μπόχα, ψέμμα και διαστροφή. Αυτό το λέω επειδή, έχοντας ζήσει από το 2010 στην Ανατολική Αφρική και γνωρίσει από κοντά χιλιάδες ανθρώπους (και ορισμένους ιδιαίτερα καλά, από πολύ κοντά, και κατόπιν μεγάλων συζητήσεων), μπορώ να αντιληφθώ πολύ καλά και με μεγάλη ακρίβεια

α. πόσο μεγάλη είναι η ανά τον κόσμο παραπληροφόρηση κι αποπληροφόρηση

β. πόσο διαφορετική είναι η κατά τόπους πραγματικότητα

γ. πόσο σωστά κι αληθινά ήταν όσα απίθανα μου είχε αρχικά πει για την Ανατολική Αφρική ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης (ο οποίος μάλιστα είχε διδάξει και σε πανεπιστήμιο στο Μογκαντίσου της Σομαλίας το 2012–2013) που, αν τα συγκέντρωνα όλα σε ένα κείμενο, πολλοί ανά τον κόσμο βλάκες, αποχαυνωμένοι από τα ψέμματα των ΜΜΕ, θα νόμιζαν ότι γράφω σουρεαλιστική λογοτεχνία!

Β. Ψέμμα ότι το Ιράν είναι Ένα Σιιτικό Κράτος

Μετά τα παραπάνω, μπορώ να επιστρέψω στο κυρίως θέμα, δηλαδή το Ιράν, την Τουρκία και τους Κιζιλμπάσηδες. Η ανασκευή των βασικών ψευδών που πιστεύει ο μέσος Έλληνας κι ο μέσος δυτικός σχετικά με τις δυο χώρες έχει λοιπόν προτεραιότητα.

Όταν κάποιος ισχυρίζεται ότι η λεγόμενη Ισλαμική Δημοκρατία του Ιράν είναι ένα σιιτικό κράτος, μπορείτε και να γελάσετε και να τον φτύσετε στα μούτρα για την μιζέρια, την βλακεία και την τύφλα του!

Η Ισλαμική Δημοκρατία του Ιράν στήθηκε πάνω σε οικτρούς νεολογισμούς τους οποίους συνέθεσαν ως θεωρία στις δεκαετίες του 1930 και 1940 ο Αγιατολλάχ Χομεϊνί κι άλλοι Ιρανοί κι Ιρακινοί Αγιατολλάχ. Όταν λέω ‘νεολογισμούς’, εννοώ προκλητικά ανιστόρητα σχήματα κι ιδεολογίες που δεν είχαν ποτέ προϋπάρξει μέσα στον σιιτικό κόσμο.

Έχω μάθει να κρίνω τους βουδιστές με βουδιστικά μέτρα, τους Χριστιανούς με χριστιανικά μέτρα, κοκ. Οπότε, το ίδιο θα κάνω και στην περίπτωση των Σιιτών (Ιράν), Αλεβιτών (Συρία) κι Αλεβίδων (Τουρκία): δεν θα χρησιμοποιήσω σουνιτικά μουσουλμανικά μέτρα και κριτήρια για να εξετάσω την εξέλιξη των ιδεών ανάμεσα στους Σιίτες θεολόγους και θεωρητικούς του 20ου αιώνα.

Αυτό θα ήταν τόσο ηλίθιο όσο τα όσα προτείνουν συχνά-πυκνά τα διεθνή ΜΜΕ που μεθοδικά αποβλακώνουν τους αποδέκτες των χαλκευμάτων τους.

Υπάρχει λοιπόν μια απόλυτη ιστορική αλήθεια: μέχρι και τον τελευταίο ψευτο-σάχη, όλα τα σιιτικά καθεστώτα ήταν βασίλεια.

Κάνω λόγο για ψευτο-σάχη επειδή το θλιβερό αυτό και κακόμοιρο άτομο ήταν ένας άθλιος γύφτουλας και γιος ενός άξεστου κι αμόρφωτου στρατιώτη που με βίαιη επέμβαση επέβαλαν οι Άγγλοι στο Ιράν, καθαιρώντας την νόμιμη, τουρκμενική δυναστεία Κατζάρ.

Η ψευτο-‘δυναστεία’ Παχλεβί επιβλήθηκε από Άγγλους μασώνους οριενταλιστές κι αποικιοκράτες με σκοπό να ελεγχθεί το Ιράν και να ρυμουλκυθεί κατά τα αγγλικά συμφέροντα: ούτε το ιστορικό όνομα ‘Παχλεβί’ δεν γνώριζε ο αγροίκος πατέρας του τελευταίου ψευτο-σάχη, όταν από την βρωμιά και την εθνοπροδοσία του αποδέχθηκε την πρόταση Άγγλων στρατιωτικών να τον στηρίξουν για να γίνει ‘σάχης’!

Άγγλοι οριενταλιστές του το έμαθαν, το όνομα αυτό!

Και κείνος το έκανε ‘δικό’ του.

Ο νεαρός Χομεϊνί σε ηλικία 36 ετών το 1938

Όμως στην δεκαετία του 1930, ο νεαρός τότε Αγιατολλάχ Χομεϊνί και πολλοί άλλοι Ιρανοί θεολόγοι ήλθαν σε ρήξη με το καθεστώς ανδρεικέλων της ψευτο-‘δυναστείας’ Παχλεβί κι άρχισαν να μελετούν τρόπους αντίδρασης κι εναλλακτικές λύσεις.

Τότε λοιπόν προσεγγίστηκαν, χωρίς να το αντιληφθούν, από όργανα των γαλλικών και των αγγλικών μυστικών υπηρεσιών που παρέχοντάς τους υλική βοήθεια τους υπέβαλαν τεχνηέντως ‘ιδέες’ που απολύτως ταίριαζαν με τα δυτικά συμφέροντα: τα γαλλικά, τα οποία υποστηρίζουν την διάδοση κι ανά τον κόσμο επιβολή ‘ρεπουμπλικανικών’ καθεστώτων, και τα αγγλικά, τα οποία επιζητούν την κατάργηση των άλλων μοναρχιών, ώστε μόνη ανά τον κόσμο μοναρχία να παραμείνει η αγγλική.

Έτσι, προέκυψε σε θεωρητικό επίπεδο αρχικά το άνομο, ψευτο-σιιτικό καθεστώς ‘Βελαγιάτ-ε Φακίχ’ (φαρσί ولایت فقیه; αραβ. ولاية الفقيه; αγγλ. Wilāyat al-Faqīh). Αυτό είθισται να αποδίδεται στις σημαντικές διεθνείς γλώσσες ως Statthalterschaft des Rechtsgelehrten, Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist, государство просвещённых.

Ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης το αποδίδει στα ελληνικά ως ‘Επιτροπεία Νομομαθών’. Μάλιστα μου έχει εξηγήσει ότι προτιμάει αυτόν τον όρο επειδή στα ελληνικά η λέξη ‘επιτροπεία’ χαρακτηρίζεται από μια προσωρινότητα, καθώς αποτελεί ουσιαστικά ένα είδος εκχώρησης του δικαιώματος διαχείρισης ή διοίκησης ή διακυβέρνησης.

Το θέμα είναι τεράστιο για να το παρουσιάσω στα πλαίσια του παρόντος κειμένου αλλά το αναφέρω επειδή αυτό το θεωρητικά επινοημένο (και ιστορικά ανύπαρκτο) καθεστώς απετέλεσε το αρχικό, θεωρητικό πρότυπο και το ‘ιδεώδες’ που, δεκαετίες αργότερα, ο Χομεϊνί αποπειράθηκε να επιβάλει ως Ισλαμική Δημοκρατία του Ιράν. Με άλλα λόγια, η ‘Βελαγιάτ-ε Φακίχ’ είναι θεσπισμένη στο ιρανικό ‘σύνταγμα’.

Αλλά ποτέ πιο πριν, κανένας σιίτης θεολόγος, φιλόσοφος, θεωρητικός της εξουσίας, διανοητής και νομομαθής δεν είχε προτείνει κάτι τέτοιο. Έχω αναφερθεί στον κορυφαίο μουσουλμάνο θεωρητικό της εξουσίας, φιλόσοφο και πολυμαθή, μέντορα και βεζύρη του Αλπ Αρσλάν και του Μάλεκ Σάχη, Νιζάμ αλ Μουλκ, ο οποίος ήταν σύγχρονος του Μιχαήλ Ψελλού. Σχετικά:

Μιχαήλ Ψελλός, Νιζάμ αλ Μουλκ, Ρωμανός Δ’ Διογένης, Αλπ Αρσλάν, κι η Πικρή Σελτζουκική Νίκη στο Μαντζικέρτ — 26 Αυγούστου 1071

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2018/08/28/μιχαήλ-ψελλός-νιζάμ-αλ-μουλκ-ρωμανός-δ/

Ο Μυστικός Νικητής της Μάχης του Μαντζικέρτ: Νιζάμ αλ Μουλκ, ο Πέρσης Δάσκαλος και Παντοδύναμος Βεζύρης του Αλπ Αρσλάν

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/08/25/ο-μυστικός-νικητής-της-μάχης-του-μαντζ/

Αλλά στο περίφημο έργο του Σιασάτ-ναμέ (Siyāsatnāmeh: ‘το Βιβλίο της Εξουσίας’), ο περίφημος σιίτης θεωρητικός που άφησε την μεγαλύτερη παράδοση ανάλυσης τρόπων εξουσίας μεσα στο Ισλάμ, ο Νιζάμ αλ Μουλκ, αν και σιίτης, δεν είδε καμμιά άλλη δυνατότητα οργάνωσης μιας ισλαμικής κοινωνίας παρά μόνον ένα βασίλειο.

Αν η μπούρδα ‘Βελαγιάτ-ε Φακίχ’ του Χομεϊνί και μερικών άλλων Αγιατολλάχ της εποχής του για μια κοινωνία οργανωμένη κατά τα δυτικά πρότυπα ως ‘δημοκρατία’ (republic) μέσα στον ισλαμικό κόσμο είχε διατυπωθεί στο Ιράν 100 ή 200 χρόνια νωρίτερα, όταν δεν κυριαρχούσαν οι Άγγλοι αποικιοκράτες, οιοσδήποτε και αν ήταν ο διεστραμμένος αυτός θεωρητικός (που θα συνηγορούσε για ένα αβασίλευτο κράτος διοικημένο από θεολόγους νομομαθείς), θα θανατωνόταν ως επικίνδυνος αιρετικός. Τόσο διεστραμμένα αντι-σιιτικό είναι το δυτικότροπο έκτρωμα του Χομεϊνί ‘Βελαγιάτ-ε Φακίχ’….

Με τα ιστορικά σιιτικά μέτρα και κριτήρια κρινόμενο αυτό το σύστημα είναι απόλυτα σατανικό. Οπότε, το σημερινό Ιράν, το οποίο παρουσιάζεται ως σιιτικό από τα διεθνή ΜΜΕ, είναι ένα εντελώς ψευτο-σιιτικό κράτος, μια άθλια καρικατούρα χρήσιμη μόνον για ιησουϊτικά, ψευτομασωνικά και σιωνιστικά παιχνίδια παγκοσμιοποίησης. Είναι αυτονόητο ότι οι δήθεν νόμοι του είναι άνομοι, γιατί ένας νόμος δεν υφίσταται, αν έρχεται σε αντίθεση με ηθικές αρχές και αξίες αποκρυσταλλωμένες σε άλλους νόμους που είχαν τηρηθεί στην διάρκεια της Ιστορίας μέχρι την στιγμή που επινοήθηκαν οι νεωτεριστικοί και άνομοι νόμοι.

Αυτά όλα σχετικά με το Ιράν μπορεί να μην τα ξέρει σήμερα ένας Έλληνας, ένας Ιταλός ή ένας Ισπανός, αλλά ένας Ιρανός χωρικός τα ξέρει και τα αντιλαμβάνεται πολύ καλά. Ξέρει ότι ένα πραγματικό σιιτικό κράτος θέλει βασιλιά κι όχι πρόεδρο της δημοκρατίας κι από πάνω ένα θρησκευτικό ηγέτη — ‘ιμάμη’.

Γ. Γιατί το Σημερινό Ιράν τρέμει στην Ιδέα μιας Ανόδου των Τούρκων Κιζιλμπάσηδων στην Εξουσία

Όπως το ιρανικό καθεστώς είναι μια ψευτο-σιιτική κωμωδία, έτσι και το ισλαμικό κατεστημένο περί τον Ερντογάν είναι μια ψευτο-οθωμανική φάρσα. Μάλιστα, αντίθετα με το ιρανικό καθεστώς, το περί τον Ερντογάν κατεστημένο δεν κατάφερε ποτέ και παρά τις προσπάθειές του να γίνει ένα καθεστώς.

Ενόσω προσπαθούσε να εκτοπίσει το πανίσχυρο στρατιωτικό κεμαλικό καθεστώς, το περί τον Ερντογάν κατεστημένο επέτρεψε στο παντουρανιστικό τμήμα του στρατιωτικού καθεστώτος να ενισχυθεί, ενόσω το ίδιο το ανερχόμενο ισλαμιστικό περί τον Ερντογάν κατεστημένο διαιρέθηκε (με την προξενημένη από τους παντουρανιστές σύγκρουση των γκιουλενικών με τους ερντογανικούς).

Και αφού οι γκιουλενικοί εκδιώχθηκαν σε πολύ μεγάλο βαθμό, το τουρκικό καθεστώς είναι κυριολεκτικά τριχοτομημένο ανάμεσα σε κεμαλιστές, παντουρανιστές και ερντογανικούς ισλαμιστές. Ακόμη χειρότερα για τον Ερντογάν, υποχρεώθηκε από την συνεργασία του με τους παντουρανιστές να βάλει πολύ νερό στο κρασί του (αν κι η έκφραση δεν ταιριάζει σε ένα ισλαμιστή όπως ο Ερντογάν, ο οποίος δεν πίνει κρασί!).

Όλα αυτά ήταν αρκετά καλοδεχούμενα για το ψευτο-σιιτικό ιρανικό καθεστώς γιατί, αν παρέμενε πανίσχυρο το κεμαλικό καθεστώς, η Τουρκία δεν θα συνεργαζόταν καθόλου με το Ιράν, και αν επιβαλλόταν της μιας ή της άλλης πλευράς (Φετουλάχ Γκιουλέν ή Ερντογάν) ισλαμιστικό καθεστώς στην Τουρκία, η χώρα θα γινόταν ένας σουνιτικός, έντονα αντισιιτικός, πόλος ο οποίος θα στεφόταν κατά του Ιράν περισσότερο από όσο στρέφεται κατά της Τεχεράνης το Ριάντ σήμερα.

Από την άλλη, το Ιράν γνωρίζει πολύ καλά ότι είτε οι γκιουλενικοί είτε οι ερντογανικοί δεν εκπροσωπούν παρά μόνον ένα τμήμα των μουσουλμάνων της Τουρκίας. Ο Φετουλάχ Γκιουλέν και το κίνημά του παραδοσιακά έπαιρναν στάσεις που χαρακτηρίζονταν από τα δυτικά ΜΜΕ ως ‘σούφι’, αλλά αυτό ήταν ένα ψέμμα και μια προπαγάνδα που κανένας ποτέ δεν πίστεψε στο Ιράν (πόσο μάλλον στην Τουρκία). Ο Γκιουλέν είναι ένας σουνίτης ψευτο-σούφι που πάντα προσπάθησε να προσεταιριστεί τους Αλεβίδες αλλά δεν τα κατάφερε. Κι ο Ερντογάν είναι πολύ πιο καθαρά σουνίτης.

Βέβαια, η άνοδος των ισλαμιστών στην Τουρκία έφερε σημαντικές αλλαγές στην τουρκική καθημερινότητα, κι έτσι τώρα οι Αλεβίδες αυτοπροσδιορίζονται πιο εύκολα σε δημόσιο επίπεδο. Κάποιες μπεκτασικές οργανώσεις έχουν ανασυσταθεί και αρκετοί τεκέδες έχουν ανοίξει κι έτσι επαναλαμβάνονται θρησκευτικές τελετές των Αλεβίδων και αρκετά τελετουργικά των Μπεκτασήδων.

Ο θρησκευτικός χορός Σαμάα είναι πλέον αντικείμενο της τουρκικής καθημερινότητας από τους δρόμους της Σεβαστείας μέχρι τις πλατείες του Αντίγιαμαν και του Μπινγκέλ, ή επίσης στην μεγαλούπολη Σταμπούλ. Αλλά σε πολιτικό επίπεδο οι Αλεβήδες είναι πολύ πιο κοντά στον κεμαλιστή ηγέτη της αντιπολίτευσης Κεμάλ Κιλιτσντάρογλου, ο οποίος δημόσια δηλώνει Αλεβίδης.

Ένα φαινόμενο που οι Ιρανοί έχουν επίσης παρατηρήσει στην Τουρκία είναι ότι υπάρχει μια κάποια αργή και βαθμιαία επιστροφή σε θρησκευτικά σχήματα και πρακτικές ακόμη και των ίδιων των κεμαλιστών στην Τουρκία — κάτι το παλιότερα αδιανόητο.

Έως αυτού του σημείου τα πάντα πηγαίνουν καλά μεταξύ Τουρκίας και Ιράν. Αλλά μια σημαντική άνοδος των Κιζιλμπάσηδων θα ήταν μια ανεξέλεγκτη δυναμική που θα έφερνε την Τουρκία έξω από την επιρροή των δυτικο-φτειαγμένων ισλαμιστών (που είναι κυρίως σουνίτες Τούρκοι) και που θα κινητοποιούσε αποσταθεροποιητικά και εθνικά απελευθερωτικά κινήματα και αντικαθεστωτικές οργανώσεις και θεολογικές σχολές και φυλετικές μειονότητες στο Ιράν.

Δ. Πως θα αντιδρούσαν οι Κασκάι του Ιράν σε μια Άνοδο των Τούρκων Κιζιλμπάσηδων στην Εξουσία

Εδώ έχει κάποιος να κάνει με ένα άλλο σημείο άγνοιας περί το Ισλάμ που έχουν οι περισσότεροι στην Δύση και συστηματικής παραπληροφόρησης εκ μέρους των δυτικών ΜΜΕ. Το σημείο αυτό είναι το εξής:

Παραδοσιακοί μουσουλμάνοι σε επαρχίες, κωμοπόλεις, χωριά, οικισμούς και νομαδικούς καταυλισμούς δεν είναι ποτέ ριζοσπαστικοί και — ακόμη χειρότερα για τις δυτικές μυστικές υπηρεσίες — δεν ριζοσπαστικοποιούνται ποτέ.

Είναι ανεκτικοί στην διαφορά και δείχνουν κατανόηση στην διαφορετικότητα.

Δεν είναι επιθετικοί και δεν επιχειρούν να επιβάλλουν την πίστη τους σε άλλους.

Αυτοί που ριζοσπαστικοποιούνται είτε στο σουνιτικό είτε στο σιιτικό μουσουλμανικό κόσμο είναι οι αστικοί πληθυσμοί και — κυρίως — οι πιο μορφωμένοι ανάμεσά τους.

Είτε ανήκουν στο πολιτικό ισλάμ (: Αδελφοί Μουσουλμάνοι) είτε στους ουαχαμπιστές της Σαουδικής Αραβίας (που είναι τα δυο μεγάλα παρακλάδια του φανατικού, ισλαμικού εξτρεμισμού και φονταμενταλισμού), οι έντονα ριζοσπαστικοποιημένοι μουσουλμάνοι (σε οποιαδήποτε χώρα κι αν ζουν στην Ασία, την Ευρώπη και την Αφρική) είναι κατά τα 99.9% τους κάτοικοι μεγαλουπόλεων, πολιτικοί μηχανικοί, μηχανολόγοι, απόφοιτοι πολυτεχνείων, νομικών και πολιτικών — κοινωνικών σχολών.

Η αιτία είναι απλή: στις μεγαλουπόλεις οι άνθρωποι έρχονται σε αντιπαράθεση με αντίθετες ιδέες και προξενούνται πολιτισμικά σοκ.

Στα χωριά και στην φύση, η ζωή είναι η ίδια σχεδόν όπως πάντοτε.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Ολότελα άσχετο από την ισλαμική τρομοκρατία είναι το απόλυτα παραδοσιακό Ισλάμ, όπως βιώνεται από τους τουρκόφωνους Κασκάι που συνέβαλαν τα μέγιστα στην ιστορική στρατιωτική οργάνωση των Κιζιλμπάσηδων.

— — — — — — — — — — — —

Αυτό ήταν από δεκαετίες γνωστό σε Αμερικανούς, Γάλλους και Άγγλους και γι’ αυτό οι διπλωμάτες των χωρών αυτών, για να προκαλέσουν τον ισλαμικό εξτρεμισμό και την ισλαμική τρομοκρατία, όπως εμφανώς τα υπεκίνησαν, δυσφημούσαν συστηματικά στα μάτια των ανά χώρα συνομιλητών τους (δηλαδή υπουργούς, πρωθυπουργούς, κοκ) τους εκεί αγροτικούς πληθυσμούς που ακολουθούσαν το τελείως παραδοσιακό Ισλάμ και τους χαρακτήριζαν ως επικίνδυνους επειδή φυσικά απέρριπταν τον δυτικό τρόπο ζωής.

Και είναι εκείνοι οι διπλωμάτες που επίμονα απαιτούσαν από ντόπιους συνομιλητές σε Μαυριτανία, Νιγηρία, Σουδάν, Αλγερία, Σομαλία, Πακιστάν, Μπάνγκλα Ντες, Ινδονησία, κλπ να στέλνουν ντόπιους φοιτητές θεολογικών σχολών στην Αίγυπτο και την Σαουδική Αραβία για να σπουδάσουν “για να μην είναι εξτρεμιστές”.

Και καθώς οι ντόπιοι υπουργοί, πρωθυπουργοί, κλπ που ήθελαν να τα έχουν καλά με τις δυτικές πρεσβείες έστελναν τους δικούς τους φοιτητές ισλαμικής θεολογίας στην Αίγυπτο και στην Σαουδική Αραβία για να σπουδάσουν, προκλήθηκε το φαινόμενο του φανατισμού, της αμορφωσιάς, του αβυσσαλέου αντιδυτικού μίσους, και σε τελική φάση της ισλαμικής τρομοκρατίας.

Οι θεολογικές σχολές Αλ Άζχαρ της Αιγύπτου (στο Κάιρο και σε πολλές άλλες πόλεις), της Μεδίνας και της Μέκκας είναι οι βασικοί πυλώνες της ισλαμικής τρομοκρατίας και εκεί εφοίτησαν ή από τους εκεί φοιτήσαντες εξαρτούνται όλες οι ηγετικές μορφές της ανά τον κόσμο ισλαμικής τρομοκρατίας.

Τα παραπάνω είναι πολύ καλά γνωστά και στο ιρανικό καθεστώς (που δεν έχει ποτέ στείλει φοιτητές θεολογίας στον βούρκο του τρομοκρατικού Καΐρου ή στους μορφωτικούς απόπατους που αποκαλούνται ‘πανεπιστήμια’ στην Σαουδική Αραβία). Οπότε, η παρατηρούμενη επανάκαμψη των Κιζιλμπάσηδων στην Τουρκία είναι ένα φαινόμενο που προχωρεί πάνω σε εντελώς αντίθετη τροχιά από το φαινόμενο του ισλαμικού εξτρεμισμού που γνωρίσαμε μέχρι σήμερα.

Αλλά αυτό είναι ‘άσχημα νέα’ για τον Ερντογάν και για το ιρανικό κατεστημένο. Οι εθνικές μειονότητες του Ιράν θα εύρισκαν σε ένα τουρκικό κιζιλμπάσικο κατεστημένο τους πρώτους συνεργάτες σε μια εξέγερση κατά των ψευτο-σιιτών Αγιατολλάχ του Κομ, της Μασάντ και της Τεχεράνης. Οι παραδοσιακοί σιίτες του Ιράν γνωρίζουν πολύ καλά πόσο ψεύτικο κι αντι-σιιτικό είναι το καθεστώς που τους περιθωριοποίησε κατά τα τελευταία 40 χρόνια. Και ιδιαίτερα οι Κασκάι έχουν ένα παρελθόν ημι-αυτονομίας, δυναμικών αντιδράσεων σε καθεστώτα, και έντονου ακτιβισμού.

Περισσότερα για τους Κασκάι και την πρόσφατη ιστορία τους θα βρείτε παρακάτω. Στο θέμα θα επανέλθω για να καταδείξω πόσο διαφορετικός είναι ο τρόπος ζωής τους από εκείνον των ισλαμιστών και εξτρεμιστών των μεγαλουπόλεων. Στο τέλος θα βρείτε πολλά για την επινόηση ‘Βελαγιάτ-ε Φακίχ’ του Χομεϊνί που τόσο χρησίμευσε και χρησιμεύει στην Αγγλία και στην Γαλλία, σε ορισμένες δυτικές μυστικές εταιρείες, και στα σχέδια παγκοσμιοποίησης που εκείνες προωθούν — εις βάρος όλων των Ιρανών.

==================

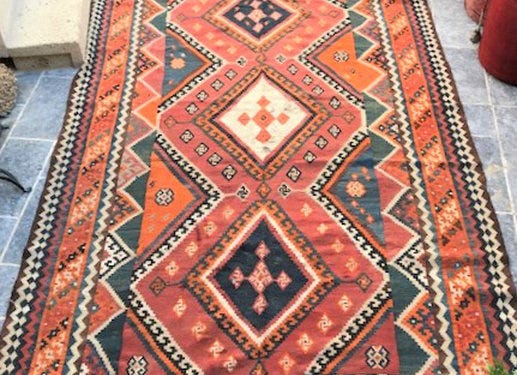

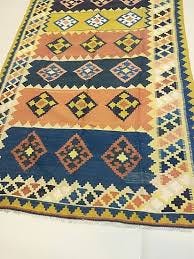

Τα φημισμένα χαλιά των Κασκάι

Διαβάστε:

Qašqāʾi Tribal Confederacy

i. History

Like most present-day tribal confederacies in Persia, the Il-e Qašqāʾi is a conglomeration of clans of different ethnic origins, Lori, Kurdish, Arab and Turkic. But most of the Qašqāʾi are of Turkic origin, and almost all of them speak a Western Ghuz Turkic dialect which they call Turki. The Qašqāʾi, in general, believe that their ancestors came to Persia from Turkestan in the vanguard of the armies of Hulāgu Khan or Timur Leng. However, it seems more probable that they arrived during the great tribal migrations of the 11th century. In all likelihood, they spent some time in Northwestern Persia before making their way to Fars.

Until recently, there was a clan by the name of Moḡānlu among them, a name which is undoubtedly derived from that of the Moḡān steppe, north of Ardabil, in Persian Azerbaijan. The clan names of Āq Qoyunlu, Qarā Qoyunlu, Beygdeli and Musellu also suggest a past connection with Northwestern Persia. Moreover, the Qašqāʾi often refer to Ardabil as their former home.

A close relationship appears to have existed at one time between the Qašqāʾi and the Ḵalaj, one branch of whom made its way to Azerbaijan and Anatolia, and another branch of whom settled down in the area known as Ḵalajestān in Central Persia, probably in Seljuqid times. Indeed, several authors, including Ḥasan Fasāʾi, have gone so far as to argue that the Qašqāʾi are but an offshoot of the Ḵalaj tribe (Fars Nāma II, p. 312).

Vladimir Minorsky, however, believed that the migration of Ḵalaj nomads from Central Persia to Fars antedated that of the Qašqāʾi and that the two groups merged when already in their present tribal territories (Personal interview, 1956). In any case, there are considerable Ḵalaj remnants among the Qašqāʾi (see Garrod, p. 294), and there is also a large group of sedentary Ḵalaj on the Deh Bid plateau, north of Shiraz, who claim to have belonged, while still nomadic, to the Il-e Qašqāʾi .

A list of Qašqāʾi clan names shows that, besides the Ḵalaj, some Afšār, Bayāt, Qājār, Qarāgozlu, Šāmlu and Igder also joined the tribal confederacy (Oberling, The Qashqa’i Nomads of Fars, p. 30).

Precisely when the Turkic components of the Il-e Qašqāʾi established themselves in Southern Persia is still shrouded in mystery. Many Qašqāʾi believe that their ancestors were sent to Fars by Shah Esmāʾil Ṣafavi (r. 1501–1524) to protect the province from the incursions of the Portuguese. But we know that their summer quarters were close to the present ones already at the beginning of the 15th century, for Ebn Šahāb Yazdi mentions a group of them who were summering at Gandomān, in northwestern Fars, in 1415 (Aubin, p. 504, n. 24).

Equally uncertain is the etymology of the name Qašqāʾi . The most plausible theory, and one which was first advanced by Wilhelm Barthold (“Kashkai,” EI ¹ II, p. 790), is that it is derived from the Turkic word qašqā, which means “a horse with a white spot on its forehead.” According to another theory, which was first proposed by Ḥasan Fasāʾi (Fars Nāma II, p. 312), the name comes from the Turkic verb qāčmaq, “to flee.”

The Qašqāʾi chiefs have all belonged to the Šāhilu clan of the ʿAmala tribe. The earliest known leader of the tribe was Amir Ḡāzi Šāhilu, who lived in the 16th century and is buried in a village called Darviš, in the vicinity of Gandomān. He was apparently a holy man, for his grave is a center of pilgrimage. According to legend, he helped shah Esmāʾil establish Shiʿism as the official faith of Persia.But it is only at the beginning of the 18th century that the Il-e Qašqāʾi began to play a significant role in the history of Fars province.

At that time, the chief of the Qašqāʾi was Jān Moḥammad Āqā, popularly known as Jāni Āqā. According to Moḥammad Ḥāšem Āṣaf (Rostam al-Tawāriḵ, p. 105), another Qašqāʾi leader, Ḥamid Beyg Qašqāʾi, was a prominent person during the reign of Shah Ḥosayn I Ṣafavi (r. 1694–1722).

According to legend, Jāni Āqā’s two sons, Esmāʾil Khan (who succeeded him as chief) and Ḥasan Khan took an active part in Nāder Shah’s conquest of India in 1738–1739. But it is said that during the campaign they ran afoul of the Afšār ruler, with the result that Esmāʿil Khan was blinded and Ḥasan Khan was so severely mutilated that he died shortly afterward. The Qašqāʾi tribes were then forced to move to the districts of Darregāz, Kalāt-e Nāderi and Saraḵs in Ḵorāsān.

While Karim Khan Zand ruled from Esfahan (1751–1765), Esmāʿil Khan wrote him a letter asking him to allow his tribes to return to their former pastures in Fars. On the verso of this letter, Karim Khan answered in the affirmative. Thus, the Qašqāʾi were able to return to Fars. Later, Esmāʿil Khan became a confident of the Vakil (Rostam al-Tawāriḵ, pp. 337, 343), and one is tempted to believe that he is the blind man standing immediately to the left of Karim Khan and identified simply as “Esmāʿil Khan” in the picture which is to be found on the cover of Add. 24,904 in the British Museum.

During the period of anarchy that followed the death of Karim Khan in 1779, Esmāʿil Khan threw in his lot with Zaki Khan, claiming for himself the title of governor of Fars province, but when Zaki Khan was slain, Esmāʿil Khan was executed by another contender for the crown, ʿAli Morād Khan. Esmāʿil was succeeded as chief by his only son, Jān Moḥammad Khan, popularly known as Jāni Khan, who backed Jaʿfar Khan (whose father, Ṣādeq Khan, had likewise been murdered by ʿAli Morād Khan).

In 1788, Āqā Moḥammad Khan Qājār launched a campaign against the Qašqāʾi in the Gandomān region. But the Qašqāʾi, having been forewarned of the impending attack, retreated to safety in the mountains. After the assassination of Jaʿfar Khan in 1789, Jāni Khan supported that ruler’s son, Loṭf ʿAli Khan.

Διαδήλωση με αναγραμμένο το όνομα του έθνους των Κασκάι στα φαρσί

When Āqā Moḥammad Khan defeated Loṭf ʿAli Khan in 1794 and established the Qājār dynasty, Jāni Khan and his family withdrew into the Zagros mountains, where they remained in hiding until the murder of the Qājār ruler in 1797. Āqā Moḥammad Khan revenged himself upon the Il-e Qašqāʾi by moving some of its component tribes (including the ʿAbd al-Maleki) to Northern Persia.

On the other hand, during this period a large number of Luri and Kurdish tribes, which had followed Karim Khan to Fars, joined the Il-e Qašqāʾi, thus greatly enlarging it.

In 1818/19, Jāni Khan was given the title of ilḵāni, which, Fasāʾi claims, was the first time that title had been used in Fars (Fars Nāma I, p. 267). Thereafter, all the paramount chiefs of the Il-e Qašqāʾi bore that title. When he died in 1823/24, Jāni Khan was succeeded by his eldest son, Moḥammad ʿAli Khan. Even though Moḥammad ʿAli Khan was of trail health and led his tribes mostly from his Bāḡ-e Aram garden palace in Shiraz, he acquired enormous power, his sway extending not only over the Qašqāʾi tribes but also over such important tribes as the Bahārlu, the Aynāllu and the Nafar.

He also forged useful marital alliances with the Qājār dynasty. He married a daughter of Ḥosayn ʿAli Mirzā Farmān-Farmā, a son of Fatḥ ʿAli Shah who was governor-general of Fars province, and, later, he arranged for one of his sons to marry a sister of Moḥammad Shah Qājār (r. 1834–1848). But, in 1836, he was summoned to Tehran and then forced to reside at the Imperial Court for the rest of the shah’s reign.

Moḥammad ʿAli Khan returned to Shiraz in 1849, during the first year of Nāṣer al-Din Shah’s reign (r. 1848–1896), and died three years later. He was succeeded by his brother, Moḥammad Qoli Khan, whose powers were limited by the presence in Tehran of a strong, stable central government that was determined to stamp out tribal unrest and banditry. The new ilḵāni was forced to reside in Shiraz as a hostage for the good behavior of his tribes.

In 1861/62, Nāṣer al-Din Shah further curbed his authority by creating a rival tribal confederacy, the “Il-e Ḵamsa” (“Confederacy of Five”), consisting of the Bahārlu, Aynāllu, Nafar, Bāṣeri and Arab tribes, and headed by the rich and powerful Qawāmi family of Shiraz.

When he died in 1867/68, Moḥammad Qoli Khan was succeeded by his weak, alcoholic son, Solṭān Moḥammad Khan. Under the latter’s ineffectual leadership, the Qašqāʾi tribes faced their greatest challenge, the terrible famine of the early 1870’s.

Although Solṭān Moḥammad Khan retired from active leadership in 1871/72, he retained his title. During this period, the Qašqāʾi tribal confederacy stood on the brink of disintegration. George Nathaniel Curzon wrote: “the tribal affairs fell into the hands of smaller khans, which resulted in internal dissension.

Owing to this, about 5,000 families went over to the Bakhtiaris, and an equal number to the Iliat Khamsah, and about 4,000 families dispersed themselves to different villages” (1892, II, p. 113).

It was only in 1904, when Esmāʿil Khan Ṣowlat al-Dowla became ilḵāni, that the Qašqāʾi once more regained their former cohesion and might. At that time, Persia was ruled by the ailing, corrupt Moẓaffar al-Din Shah (1896–1907), and the authority of the central government over the provinces was steadily eroding. In Fars, Ṣowlat al-Dowla gained control of most of the tribal hinterland, while his arch-rival, Qawām al-Molk (the Qawāmi leader), established his power base in Shiraz.

During the Persian revolution of 1906–1911, Fars became the scene of unprecedented chaos as the two camps struggled for dominance. At first, probably because the Qawāmi favored the Royalists, the Qašqāʾi supported the Constitutionalists. Later, when the Baḵtiāri leaders became dominant in Tehran and the Qawāmi sided with them, Ṣowlat al-Dowla formed an anti-Baḵtiāri and anti-Qawāmi alliance with the reactionary Sheikh Ḵazʿal of Moḥammarah and Sardār-e Ašraf, the wāli of the Pošt-e Kuh, called the “Etteḥād-e Jonub” (“League of the South”).

The civil war in Fars grew even more intense as the British government became embroiled in it. The British, who established their oil concession in Ḵuzestān in 1908, felt threatened by the League of the South. They were also increasingly irritated by the high incidence of banditry and the extortionate demands of tribal toll collectors on the Bušehr-Shiraz road, which was the main artery of British trade with Persia.

Because the road passed through Qašqāʾi territory, British merchants blamed Ṣowlat al-Dowla for their losses. Thus the British Consulate in Shiraz became a focal point of pro-Qawāmi sentiment. The unrest in Fars reached its climax in July 1911, when a combined force of Qašqāʾi warriors and troops belonging to the pro-Qašqāʾi governor-general of Fars, Neẓām al-Saltana, repeatedly stormed Qawāmi positions throughout the city.

But in September, British threats of intervention and defections from Ṣowlat al-Dowla’s tribal army finally convinced the ilḵāni to withdraw from the scene. In World War I, Fars once more became a seething cauldron of conflict. After the proclamation of Jihad by Enver Pasha, it was optimistically believed by Turkish and German leaders that Muslims from French North Africa to British India would spontaneously revolt against their infidel masters, and that even such neutral states as Persia and Afghanistan would make common cause with the Ottoman Empire.

To facilitate this task, the German government planned to dispatch a whole contingent of agents provocateurs to Persia and Afghanistan. But when no uprisings took place and the Persian and Afghan governments remained stubbornly neutral, the German plans were accordingly scaled back. In the end, only two small groups of agents were sent, one to Persia and the other to Afghanistan.

The agents who were sent to Persia were headed by Wilhelm Wassmuss, who had previously been German consul in Bušehr, where he had befriended tribal leaders who resented British interference in their arms smuggling operations. In spring 1915, Wassmuss was sent to Shiraz as German consul. On his way through Southern Fars, his two German aides were arrested by the British and all his equipment, as well as his secret codes, seized. Nevertheless, during the following three years, he was able to cause such widespread mayhem in the province that he became known as the “German Lawrence.”

Anticipating the rapid destruction of British forces in Mesopotamia, he decided to open a corridor from the southeastern reaches of the Ottoman Empire to India to be used as a prospective route for an invasion of the Raj. In November, 1915, he led a coup in Shiraz together with pro-German officers of the newly-created Gendarmerie, in the course of which the British Consul and eleven other British subjects were apprehended.

The women were later released, but the men were incarcerated in the fortress of Ahram, near the Persian Gulf, which belonged to a pro-German sheikh.

However, Wassmuss’s triumph was ephemeral, for his support came mostly from the coastal tribes of Daštestān and Tangestān, which were too far from Shiraz to be of much help. In February, 1916, Qawām al-Molk, the pro-British governor-general of Fars, who had fled to British-occupied Bušehr during Wassmuss’s coup, set out for Shiraz with his British-supplied private army.

Although he was killed in a hunting accident on the way, his son, who inherited the title, completed the journey, and, together with pro-British officers of the Gendarmerie, recaptured the provincial capital. A new, British-officered Persian force, the South Persia Rifles, was then organized to prevent any further pro-German coups.

After that, Wassmuss directed most of his energies to forming new tribal alliances, especially with the kalāntar of Kāzerun and the Qašqāʾi ilḵāni. Ṣowlat al-Dowla was particularly susceptible to his appeal, for he still bore a grudge against the British for their support of the Qawāmi in 1911 and viewed the formation of the South Persia Rifles as a British plot to further increase their power.

Moreover, he was easily convinced by Wassmuss that Turkish forces which were then invading Western Persia would soon oust the British from Persia. Therefore, he finally decided to take action against the British. But he quickly learned that he had overestimated the strength of his tribal army. In May 1918, a large Qašqāʾi force attacked a detachment of the South Persia Rifles at Ḵāna Zenyān, on the Bušehr-Shiraz road.

As British troops rushed to the rescue, a major battle took place between the Qašqāʾi and the relief column. In this engagement, Qašqāʾi forces far outnumbered those of Great Britain, but they were nonetheless decisively defeated. As the war was winding down in Europe, Wassmuss fled to Qom, where he was finally captured by the British in 1919.During the reign of Reżā Shah (1925–1941), the Qašqāʾi suffered great hardship. In 1926, Ṣowlat al-Dowla and his eldest son, Nāṣer Khan, were summoned to Tehran as deputies in the new Majles, but they quickly realized that they were virtual prisoners of the Shah.

They were forced to cooperate with the central government in its efforts to disarm the Qašqāʾi tribes. Then they were stripped of their parliamentary immunity and thrown into jail. Meanwhile, military governors were assigned to the various Qašqāʾi tribes, the tribesmen were subjected to the Shah’s highly unpopular military conscription law and a new taxation system was established which was often abused by corrupt government tax collectors.

In the spring of 1929, the nomads’ resentment, which had been further exacerbated by the barbarity of some of the military governors, led to a widespread uprising in Southern Persia in which the Qašqāʾi played the leading role. After several months of fighting, the central government signed a truce according to which Ṣowlat al-Dowla and Nāṣer Khan were reinstated as members of the Majles, the military governors were withdrawn from tribal territories and a general amnesty was declared.

However, Reżā Shah was determined to put an end to the tribal system in Persia, and, just as he crushed the Lors, the Kurds and the Arabs, he finally crushed the Qašqāʾi . In 1932, the Qašqāʾi once more rebelled, but in vain. In 1933, Ṣowlat al-Dowla was put to death in one of the Shah’s prisons, and, shortly thereafter, the Shah, having decided to force the nomads to settle down upon the land, cut off their migration routes with his modern, mechanized army.

This shortsighted policy did not produce agriculturists, but only starving nomads, and William O. Douglas was probably right when he wrote that “they would have been wiped out in a few decades had the conditions persisted” (p. 139).

When Reżā Shah abdicated in September 1941, Nāṣer Khan and his brother Ḵosrow Khan escaped from Tehran, where they had been forced to reside, and hastened back to Fars.

Proclaiming himself ilḵāni, Nāṣer Khan reconstituted the Il-e Qašqāʾi, repossessed all the tribal territories and ordered the resumption of the tribal migrations.

But he had inherited his father’s Anglophobia and propensity for fishing in troubled waters.

Certain that the German thrust toward the Caucasus was a mere preamble to a German invasion of Persia and its liberation from the hated British, he, like his father before him, decided to back Germany in a world conflict.

Having heard that the German agent, Berthold Schulze-Holthus (of the Abwehr), was hiding in Tehran, he urged him to come to Fars in the late spring of 1942.

Thereupon, Schulze-Holthus set out for Qašqāʾi headquarters in Firuzābād and became Nāṣer Khan’s military advisor. Later, several more German agents were dropped by parachute in Qašqāʾi territory.

But few of the weapons that the Germans had promised to send to the Qašqāʾi ever materialized.

Instead of sending a British force into Fars to subdue the Qašqāʾi, the British prevailed upon the Persian government to do so.

In the spring of 1943, Persian troops were duly dispatched to the South and a series of clashes occurred with the Qašqāʾi, the Boyr Aḥmadi and other refractory tribes. In this campaign, the Persian army suffered several major defeats.

Especially devastating was the mass slaughter of the Persian garrison at Samirom by the Qašqāʾi and their Boyr Aḥmadi allies, in which the Persian army lost 200 men and three colonels.

A treaty was finally signed between the central government and Nāṣer Khan according to which the Qašqāʾi were allowed to retain their autonomy, as well as their weapons, in exchange for accepting the establishment of Persian military garrisons in Firuzābād, Farrašband and Qalʿa Pariān.

In 1943, Nāṣer Khan’s two other brothers, Malek Manṣur Khan and Moḥammad Ḥosayn Khan returned to Persia from exile in Germany.

They were arrested by the British and, in the spring of 1944, they were exchanged for Schulze-Holthus and the other German agents, whose presence among the Qašqāʾi had, by that time, become a liability for Nāṣer Khan.

In 1946, there was yet another major tribal uprising in Southern Persia. This time, it was actually encouraged by the central government. The prime minister, Aḥmad Qawām, who was under great pressure by the Soviet Union to accept a Soviet oil concession in Northern Persia, had already been coerced into accepting three Communist Tudeh Party members in his cabinet.

He felt that a widespread anti-Soviet uprising in Southern Persia would act as a counterweight to that pressure. Nāṣer Khan needed little prompting, for he detested the Soviets as much as he abhorred the British, and he calculated that if, for some reason, the Qawām government should falter, he himself might provide alternate leadership as the head of a grand anti-Communist coalition.

Ο χώρος των Κασκάι στο Ιράν είναι τα νότια τμήματα της οροσειράς του Ζάγρου.

But Nāṣer Khan also wanted to improve living conditions in Fars. Therefore, in September 1946, he called a conference of the major tribal and religious leaders of the province at Čenār Rāhdār and a “national” movement called “Saʿdun” (“The Happy Ones”) was created which demanded, among other things, the resignation of the entire cabinet, except for Premier Qawām, the allocation of two-thirds of Fars’s taxes to the province, the immediate formation of provincial councils and more representatives from Fars in the Majles.

When these demands were rejected, tribes from Ḵuzestān to Kermān rose en masse. The Qašqāʾi seized the towns of Kazerun and Ābāda, and broke through the outer defenses of Shiraz. Premier Qawām’s scheme worked to perfection, for, in October, he was able to form a new cabinet without any Tudeh Party members.

Meanwhile, he had signed an agreement which accepted most of Saʿdun’s demands. Moreover, a few months later, Ḵosrow Khan was elected as a member of Qawām’s Demokrāt-e Iran party to represent the Qašqāʾi in the Fifteenth Majles, which rejected the Soviet concession.

During the years 1945–1953, Il-e Qašqāʾi thrived as never before. It enjoyed almost complete autonomy, and, under the enlightened leadership of the “Four Brothers,” as Ṣowlat al-Dowla’s sons were called, the tribesmen prospered. Nāṣer Khan and Malek Manṣur Khan functioned as tribal leaders in Fars, while Moḥammad Ḥosayn Khan and Ḵosrow Khan represented the interests of the confederacy in the Persian capital.

But, in 1953, the Four Brothers once more displayed their anti-Pahlavi sentiments by supporting Moḥammad Moṣaddeq in his attempt to overthrow the Shah. Ḵosrow Khan severely criticized the Shah in the Majles, and, when Moṣaddeq was arrested, Qašqāʾi forces briefly threatened to seize Shiraz in a futile attempt to convince the pro-shah Zāhedi government to free him. As a result, in 1954, the Four Brothers were exiled and all their properties were confiscated by the Persian government.

During the 25 years that followed the expatriation of the Four Brothers, new efforts were undertaken by the central government to make the nomads adopt a sedentary way of life. According to Lois Beck, “Because of far-reaching disruptions brought about by scarcity of pastures, government restrictions, undermined tribal institutions, and capitalist expansion, most Qashqa’i found it exceedingly difficult to continue nomadic pastoralism” (1974, p. 251).

As a result, thousands of tribesmen moved to cities, such as Shiraz, Bušehr, Ahwāz and Ābādān, seeking work as laborers in factories and in the oil industry. With the loss of their traditional way of life, the tribesmen gradually lost the cohesion which had once made them strong, and they were unable to prevent the government from establishing direct control over them.

In 1963, the government officially declared tribes to be non-existent, and all the remaining khans were stripped of their titles and prerogatives.

So confident was the Shah that the tribal problem had at last been solved that he allowed Malek Manṣur Khan and Moḥammad Ḥosayn Khan to return to Persia, provided they stayed out of Fars province.

Many Qašqāʾi participated in the demonstrations which led to the fall of the Shah in 1979, and, during the revolution, Nāṣer Khan and Ḵosrow Khan made their way back to Persia.

At first, relations between the Qašqāʾi and the Khomeini regime were harmonious. Nāṣer Khan visited Khomeini shortly after the Ayatollah’s arrival in Tehran, and, later, Khomeini publicly praised the Qašqāʾi leaders for their assistance in maintaining order in Fars.

Although Nāṣer Khan was warmly welcomed by the Qašqāʾi, he made no attempt to restore tribal autonomy or even to resume his functions as paramount chief of the confederacy.

But Khomeini’s determination to establish a highly centralized theocratic state soon alienated the tribal population of Persia, and relations with the Four Brothers became increasingly strained.

Accusations against Ḵosrow Khan to the effect that he had been a CIA agent and an attempt by the Revolutionary Guards to arrest him in Tehran in June 1980 finally led to a complete breakdown in the relationship between the Qašqāʾi and the new regime.

Eluding his captors, Ḵosrow Khan sought refuge in the Qašqāʾi capital of Firuzābād in Eastern Fars, where he was joined by Nāṣer Khan and several other tribal chiefs. When Revolutionary Guards converged upon the town, the Qašqāʾi leaders and some 600 tribal warriors set up an armed camp in the nearby mountains.

For two years, the Qašqāʾi insurgents defied the central government and repelled repeated attacks by the Revolutionary Guards. In July 1980, Rudāba Ḵanom, Nāṣer Khan’s wife, died of diphtheria in Firuzābād. In April 1982, a surprise night attack by Revolutionary Guards who had been transported by helicopters finally compelled the Qašqāʾi to abandon their camp and move to higher ground, leaving behind all their equipment and medical supplies.

A few days later, ʿAbdollah Khan, Nāṣer Khan’s eldest son, who was the insurgents’ only doctor, died of a heart attack. This loss so devastated Nāṣer Khan that he decided to give up the struggle, and, in May 1982 he fled Persia by way of Kurdistan with the help of the Jāf Kurds.

In July, Ḵosrow Khan negotiated a settlement with the central government, which put an end to the tribal rebellion. But, in September 1982, the Islamic Revolutionary Court in Shiraz condemned him to death and he was hung in one of the city’s major squares on October 8. Several other Qašqāʾi leaders, including Malek Manṣur Khan, were also arrested.

When Nāṣer Khan died in January 1984, the history of the Il-e Qašqāʾi truly ended, for he was the last ilḵāni.

Μπορείτε να βρείτε την αναφερόμενη βιβλιογαφία εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/qasqai-tribal-confederacy-i

===============

Qašqāʾi Tribal Confederacy

Language

Qašqāʾi is a language of southwestern or Oghuz branch of Turkic languages, spoken in the Iranian provinces of Hamadan and Fārs, especially in the region to the north of Shiraz.

Until the middle of the 20th century nearly no Qašqāʾi (and Äynallu) materials had been published. The earliest records of the Qašqāʾi language were made by Aleksandr Romaskevich and Sir Aurel Stein. These materials, which are very precise descriptions of these dialects, were included in Tadeusz Kowalski’s description (Kowalski, 1937). Romaskevich collected his materials (35 phonetically recorded songs) in the region of Shiraz.

These records had remained the most extensive materials for a long time. After that, researchers like Oliver Garrod, Karl Heinrich Menges, and M. Th. Ullens de Schooten also collected materials on the Qašqāʾi language, but these were never published.

The unpublished materials of Menges (recorded in the Samirom area) are different from Kowalski’s records in many ways (Caferoğlu and Doerfer, p. 286). Later, some studies of the southwestern dialects of Turkish, or Azerbaijani, dealt with Qašqāʾi marginally and brought insignificant results (Gabain).

Further materials were collected by Wolfram Hesche, Hartwig Scheinhardt, and Semih Tezcan in the region of Firuzābād during the Turcological expeditions to Iran in 1967, 1968, and 1973, initiated by Gerhard Doerfer. Finally, these Qašqāʾi materials were published in Oghusica aus Iran (Doerfer, Hesche, and Ravanyar), together with three texts from the collection of K. H. Menges.

Extensive Qašqāʾi materials were collected by Gunnar Jarring, but they mainly remain unpublished. In the 2000s, Éva Ágnes Csató Johanson has been working on the Qašqāʾi language (Csató Johanson, 2001, 2005, 2006).

Various points of view were held regarding the relationship of Qašqāʾi to the southwestern dialects of Turkish. On the basis of Qašqāʾi samples published by Romaskevich, Kowalski wrote that the Qšqāʾi language can be defined as the dialect most closely related to the Azerbaijani language (Kowalski, p. 4).

In the same way, Annemarie von Gabain stated that in the provinces of Hamadan and Fārs, the vernaculars of Äynallu and Qašqāʾi were close to the Azerbaijani language (Gabain, p. 174). In the opinion of Gerhard Doerfer, the two languages (Äynallu and Qašqāʾi) are so close to the Azerbaijani that one can call them its dialects (Doerfer, 1969, p. 14).

K. H. Menges, on the other hand, argued that Qašqāʾi (and Äynallu) were more closely related to the Ottoman Turkish than to the Azerbaijani, and he supposed that they formed a third group of dialects within the southwestern Turkic languages.

He wrote: “Since certain Qašqāʾi dialects exhibit a greater similarity with Osman-Turkish than with Āzarbājdžānian, the study of the Qašqāʾi dialects lead me to a reconsideration of the subdivisions of the southwestern Turkish languages (Osman, Āzarbājdžānian, Türkmen): Ottoman and Azerbaijani are not two languages, but two different dialect groups of one SW Turkic language — Osmano-Āzarbājdžānian, to which as a third group belong the Qašqāʾī dialects in the South.

Thus, we have in the SW-Turkic language area two languages: Osman-Āzarbājdžān-Qašqāʾī in the West and Southwest, and Türkmen in the East of that area” (Menges, p. 278). Caferoğlu and Doerfer agreed to the fact that Qašqāʾi deviates from Azerbaijani, but refused Menges’s conception of its closer relationship to Ottoman Turkish (Caferoğlu and Doerfer, p. 281).

Yet Doerfer expressed an opinion similar to that of Menges, when he wrote that Qašqāʾi, as well as Ottoman, represented dialectal groups of one language: “But he [Menges] surely is right when he adds that Osman-Turkish and Azerbaijani actually are only dialects of one language” (Doerfer, 1970, p. 219).

Doerfer assumed that Qašqāʾi, Sonqori, and Äynallu — which was seen by Menges as a sub-dialect of Qašqāʾi only (Caferoğlu and Doerfer, p. 281) — represented transitional forms between Azerbaijani and Khorasan-Turkish (Doerfer, 1977, p. 54). Further to that, Doerfer considered the dialects spoken to the north of Ḵalajestān, Pugerd, and Āštiān (34˚ N, 50˚ E) to be closely connected with Qašqāʾi (Doerfer, 1998, p. 274).

In terms of its structure, Qašqāʾi shows some closeness to the dialects of Qazvin (northeast of Tehran) and Soleymānābād (southwest of Hamadan; see Doerfer, 1998, p. 274). The classification given in TABLE 1 demonstrates the position of Qašqāʾi, Sonqori, and Äynallu within the Oghuz branch of Turkic languages (the classification is based on Doerfer, 1975–76, pp. 81–94; Idem, 1976b, pp. 247 ff.; Idem, 1976a, pp. 137 ff.; Idem, 1978, pp. 191–97; Idem, 1990, p. 19; Idem, 1991, pp. 107–9; Doerfer and Hesche, 1988, p. 62; Idem, 1993, pp. 20–21).

Qašqāʾi seems to have the following vowels: i, e, ä, a, å, ï, u, ü, o, ö, and the following consonants: p, b, m, f, v, t, d, n, s, z, š, ž, č, 3˘, k, g, q, γ, χ, ŋ, l, r, h. According to Kowalski, there are long and short forms of all vowels (Kowalski, pp. 54 f.).

In Qašqāʾi, ä became a (e.g., man ‘I’, Kowalski, p. 55), and o/ö are narrowed to u/ü (e.g., ūlur, ülüm, Kowalski, p. 55). Initial ii-, iï-, and iü- in Qašqāʾi became i- and ü- (e.g., ulduz < iulduz, see Kowalski, p. 55; see TABLE 2).

In the vocabulary of *Qašqāʾi (as well as in that of Äynallu), the influence of Persian is recognizable. Besides that, both the materials collected by Romaskevich (cf. Kowalski, Glossar, pp. 44–53) and the texts collected in Firuzābād by Doerfer’s collaborators (Doerfer, Hesche, and Ravanyar, index, pp. 114–31) show numerous borrowed elements of Arabic origin.

The vocabulary of administration and the military has — as it would be expected — especially many words of Persian origin (e.g., pāsban ‘guardian’ < Pers. pāsbān; peykan ‘arrow-head’ < Pers. peykān; šah ‘king’ < Pers. šāh).

The religious lexicon is borrowed from Arabic, but transmitted through Persian, and, consequently, it reveals specific Persian features.

Furthermore, there is a remarkable and expected influence of Persian elements in the medical terminology (e.g., bimar ‘sick, ill’ < Pers. bimār; därd ‘pain’ < Pers. dard; dāru ‘medicine’ < Pers. dāru). Most of the toponyms are also of Persian origin or at least transmitted through it. There are a few Persian elements regarding morphology of Qašqāʾi as well as Äynallu, such as the comparative suffix –tar (e.g., yeytar ‘better’; see Caferoğlu and Doerfer, p. 300).

The syntax, too, shows numerous elements borrowed from Persian (e.g., the Persian relative particle ke > Qašq. ki, or such figures of speech as xa … xa ‘whether … or’ < Pers. ḵᵛāh … ḵᵛāh).

Μπορείτε να βρείτε την αναφερόμενη βιβλιογαφία εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/qasqai-tribal-confederacy-ii-language

===================

Σχετικά με το χομεϊνικό επινόημα ‘Βελαγιάτ-ε Φακίχ’:

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο του Mohsen Kadivar,

Wilayat al-faqih and Democracy:

https://vk.com/doc429864789_618751664

https://www.docdroid.net/qxB9xk9/mohsen-kadivar-wilayat-al-faqih-and-democracy-pdf

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο του Neil Shevlin,

Velayat-e Faqih in the Constitution of Iran:

https://vk.com/doc429864789_618752540

https://www.docdroid.net/ElPN7Vg/neil-shevlin-velayat-e-faqih-in-the-constitution-of-iran-pdf

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο της Sarah Khan,

Wilayat-e Faqih: Origin and Trajectory of Development:

https://vk.com/doc429864789_618752779

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο του Abbas Amanat,

From ijtihad to wilayat-i faqih:

https://vk.com/doc429864789_618753176

https://www.docdroid.net/4tpsXW6/abbas-amanat-from-ijtihad-to-wilayat-i-faqih-pdf

Επίσης — αν και με πολλές πολύ λαθεμένες αναφορές:

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Вилаят_аль-факих

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welāyat-e_Faqih

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guardianship_of_the_Islamic_Jurist

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_Government

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruhollah_Khomeini

Στα επόμενα, προσέξτε τα πολύ διαφορετικά οπτικά πρίσματα υπό τα οποία γράφονται τα κείμενα αυτά από εκπροσώπους διαφορετικών συμφερόντων:

— — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

No comments:

Post a Comment