Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής — Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Σε δύο πρότερα κείμενα περιέγραψα από πολλές απόψεις την τερατουργηματική δομή και την οικτρή σύσταση του ψευτοκράτους ‘Αφγανιστάν’, το οποίο χωρίς καμμιά πρότερη ιστορικότητα στήθηκε για να εξυπηρετηθούν τα αγγλικά συμφέροντα στην ευρύτερη περιοχή της Κεντρικής Ασίας, του ιρανικού οροπεδίου, της Κοιλάδας του Ινδού και της Δυτικής Κίνας. Τα κείμενα αυτά βρίσκονται εδώ:

Τατζίκοι, Παστούνοι, Χαζάρα, Ουζμπέκοι: Καταπιεσμένα Έθνη του Αφγανιστάν, ενός Τερατουργηματικού Ψευτοκράτους

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/15/τατζίκοι-παστούνοι-χαζάρα-ουζμπέκοι/

(και πλέον: https://www.academia.edu/51129166/Τατζίκοι_Παστούνοι_Χαζάρα_Ουζμπέκοι_Καταπιεσμένα_Έθνη_του_Αφγανιστάν_ενός_Τερατουργηματικού_Ψευτοκράτους)

Βακτριανή, Αριανή, Αραχωσία και Αφγανιστάν: το Ανύπαρκτο Παρελθόν ενός Ψευτο-κράτους Παρασκευασμένου από Μηχανορραφίες Άγγλων

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/16/βακτριανή-αριανή-αραχωσία-και-αφγανι/

(και πλέον: https://www.academia.edu/51162047/Βακτριανή_Αριανή_Αραχωσία_και_Αφγανιστάν_το_Ανύπαρκτο_Παρελθόν_ενός_Ψευτο_κράτους_Παρασκευασμένου_από_Μηχανορραφίες_Άγγλων)

Το Αφγανιστάν δεν είναι ένα έθνος, δεν έχει μία γλώσσα, δεν πιστεύει σε μια θρησκεία, δεν έχει ιστορικό παρελθόν και δεν αποτελεί μια γεωγραφική ενότητα παρά μόνον αν αυθαίρετα συρθούν γραμμές πάνω στον χάρτη της Ασίας από τον οιονδήποτε. Σήμερα, οι Τατζίκοι, οι Παστούνοι, οι Χαζάρα, οι Ουζμπέκοι και πληθυσμιακά μικρότερα έθνη απαρτίζουν — εντός του ψευτοκράτους ‘Αφγανιστάν — ένα καζάνι που βράζει και όπου Σουνίτες μουσουλμάνοι, Δωδεκατοϊμαμιστές Σιίτες μουσουλμάνοι και Εβδομοϊμαμιστές Σιίτες μουσουλμάνοι, μαζί με μερικές άλλες θρησκευτικές μειονότητες, αλληλοσφάζονται πάνω στην θεατρική σκηνή ‘Ισλαμικός Φονταμενταλισμός από Πολιτικό Ισλάμ και Ουαχαμπιστές’ που έστησαν δυτικά αποικιοκρατικά συμφέροντα κατά τις δικές τους, ανάμεσα σε δυτικές μυστικές υπηρεσίες, διαμάχες.

Χαζάρα: ένα Τουρκομογγολικό Σιιτικό Έθνος — Τμήμα του Κιζιλμπασικού Κινήματος

Αν οι Ουζμπέκοι του Αφγανιστάν συνενωθούν με την μητέρα πατρίδα τους, το Ουζμπεκιστάν, αν οι Τατζίκοι του Αφγανιστάν αποτελέσουν μια επαρχία του Τατζικιστάν, κι αν οι Παστούνοι του Αφγανιστάν συνενωθούν με τους ομοεθνείς τους στο Πακιστάν σε ένα νέο ανεξάρτητο κράτος-έθνος — και προσθέτω ότι όλοι αυτοί θα επιθυμούσαν κάτι τέτοιο –, τότε στο Αφγανιστάν θα απομείνουν μόνον οι Χαζάρα και η χώρα θα ονομαστεί Χαζαρεστάν, ή Χαζαρατζάτ, όπως λέγεται στην γλώσσα των Χαζάρα. Και είναι αυτονόητο ότι κάτι τέτοιο αποτελεί την ευχή όλων των Χαζάρα.

Με άλλα λόγια, αν εξετάσει κάποιος το αγγλικό αποικιοκρατικό σχέδιο της σύστασης ενός ψευτοκράτους ονόματι ‘Αφγανιστάν’ στις αρχές του 19ου αιώνα μόνο σε τοπικό επίπεδο, τότε αμέσως καταλαβαίνει ότι τα περισσότερο ζημιωμένα έθνη ήταν τελικά οι Χαζάρα και οι Παστούνοι που μέχρι σήμερα δεν απέκτησαν δικά τους κράτη-έθνη. Και ακόμη χειρότερη είναι η κατάσταση για τους Χαζάρα που στο συνήθως παστουνο-κρατούμενο Αφγανιστάν — επί βασιλικού, κομμουνιστικού, ταλιμπανικού ή ρεπουμπλικανικού καθεστώτος — οι Χαζάρα ήταν το περισσότερο καταπιεσμένο έθνος.

Εάν λοιπόν συμβούν τα παραπάνω, το Χαζαρεστάν θα αποτελεί περίπου το 40% της συνολικής έκτασης του σημερινού Αφγανιστάν και θα το θυμίζει αρκετά ως γεωγραφική έκταση, επειδή οι Χαζάρα κατοικούν στο κέντρο του Αφγανιστάν, σε μια ελλειπτικού σχήματος (όπως και το ίδιο το Αφγανιστάν) έκταση που μοιάζει να είναι ομόκεντρη με την μεγαλύτερη, σημερινή, συνοριακή γραμμή του Αφγανιστάν. Η έκταση αυτή χαρακτηρίζεται από μικρότερη αστυφιλία, αραιότερο πληθυσμό και εντονώτερη νομαδική ζωή από τις άλλες περιοχές του Αφγανιστάν.

Οι Χαζάρα είναι ένα τουρκομογγολικό φύλο, πιθανώτατα καταγόμενο από τους Τσαγατάυ Τούρκους (που σήμερα θεωρούνται ανύπαρκτο κι αφομοιωμένο σε άλλα έθνη φύλο), το οποίο αναμείχθηκε με τον εντόπιο πληθυσμό της συγκεκριμένης περιοχής.

Γλωσσικά επηρεάστηκαν από τα φαρσί σε ένα κάποιο βαθμό και, αν και σουνιτικής αρχικά πίστης, αποδέχθηκαν το Εβδομοϊμαμικό Σιιτικό Ισλάμ στα χρόνια των Σαφεβιδών.

Για πρώτη φορά στην Ιστορία, οι Χαζάρα αναφέρονται από τον Μπαμπούρ, ένα πολυμαθέστατο φιλόσοφο, ιστορικό, συγγραφέα και ηγεμόνα, ο οποίος ήταν ο θεμελιωτής της δυναστείας των Γκορκανιάν (των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων) που έστησε στις αρχές του 16ου αιώνα την τεράστια Μογγολική Αυτοκρατορία της νότιας Ασίας με κέντρο την βόρεια Ινδία.

Οι Χαζάρα ενσωμάτωσαν στις παραδόσεις τους στοιχεία της πρότερης ιστορίας της Βακτριανής στα νότια άκρα της οποίας εγκαταστάθηκαν αρχικά, για να επεκταθούν αργότερα στα ανατολικά άκρα της Αριακής και στα βόρεια σημεία της Αραχωσίας.

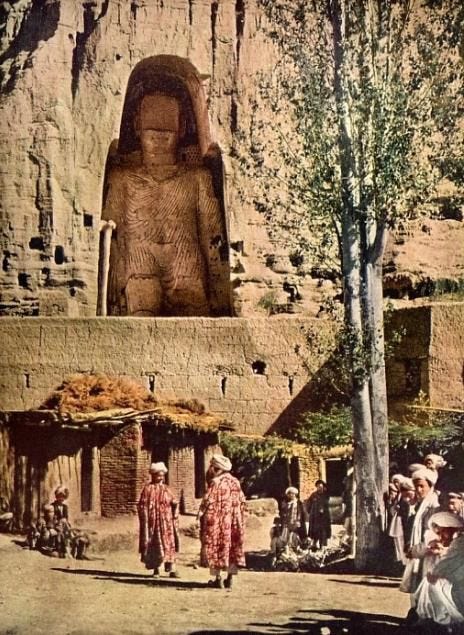

Έτσι, για παράδειγμα, τα τεράστια λαξευτά αγάλματα του Βούδα στο Μπαμιγιάν δεν ήταν για τους Χαζάρα ένα άχρηστο υλικό υπόλειμμα πρότερων πολιτισμών και αλλόθρησκων εθνών αλλά ενσωματώθηκαν στις παραδόσεις τους κι έγιναν στοιχείο της παιδείας και των δοξασιών τους.

Στο δεύτερο μισό της 2ης χιλιετίας, οι Χαζάρα υπήρξαν ως επί το πλείστον ένα ανεξάρτητο έθνος, το οποίο συνδέθηκε με το κιζιλμπασικό κίνημα και απετέλεσε την ανατολική λαβίδα του.

Χάρη σ’ αυτό το κίνημα, οι Χαζάρα διετήρησαν σε μεγάλο βαθμό την ανεξαρτησία τους μέχρι τα τέλη του 19ου αιώνα και τις αρχές του 20ου αιώνα, όταν μετά από παστουνική, αφγανική, σουνιτική τζιχάντ εναντίον τους βιαίως και μετά από πολύ αίμα προσαρτήθηκαν στο ψευτο-βασίλειο ‘Αφγανιστάν’.

Αντίθετα από τους Παστούνους που πίστεψαν τις υποκριτικές φιλοφρονήσεις, τις άθλιες κολακείες και τις ψεύτικες υποσχέσεις των Άγγλων αποικιοκρατών του 19ου και του 20ου αιώνα (κι έτσι χρησιμοποιήθηκαν εις βάρος των δικών τους συμφερόντων και μετατράπηκαν σε εργαλείο της αγγλικής και της αμερικανικής διπλωματίας μέχρι και σήμερα στον σχηματισμό του αφγανικού ισλαμιστικού ταλιμπανικού κινήματος), οι Χαζάρα εξυπαρχής απέρριψαν κάθε αποικιοκρατική προσέγγιση, αντιμετώπισαν κάθε δυτικό διπλωμάτη αρνητικά, απορριπτικά και με δυσπιστία (το οποίο και πλήρωσαν γιατί οι Άγγλοι κι οι Αμερικανοί έστρεψαν τους Παστούνους και τις αρχές του ψευτοκράτους ‘Αφγανιστάν’ εναντίον των Χαζάρα για να τους εκδικηθούν), και παραμένουν έτσι ένα από τα ελάχιστα έθνη στον κόσμο που δεν έχει διαβρωθεί από την δυτική νοοτροπία και διαφθορά και μια από τις πολύ σπάνιες κοινωνίες μέσα στις οποίες δεν έχουν διηθηθεί και παρεσιφρύσει (με τον ένα ή με τον άλλο τρόπο) δυτικοί ή άλλοι πράκτορες.

Η νομαδική φύση της καθημερινής ζωής για την πλειοψηφία των Χαζάρα και η συνεχής παρουσία του κιζιλμπασικού κινήματος προστάτεψαν το έθνος αυτό και το διετήρησαν ανέπαφο από ξενικές επιδράσεις.

Γι’ αυτό κι ο ρόλος των Χαζάρα στις εξελίξεις στην ευρύτερη περιοχή της Κεντρικής Ασίας, του Καυκάσου, του ιρανικού οροπεδίου και της Ανατολίας κατά τα επόμενα χρόνια δεν μπορεί παρά να αυξηθεί.

Μια μυστική γραμμή συνδέει την Κεντρική Ανατολία της Τουρκίας, την Τσετσενία, το Νταγεστάν, το Αζερμπαϊτζάν, το βορειοδυτικό (αζερικό) και το νότιο (Κασκάι) Ιράν, καθώς και τους Χαζάρα του Αφγανιστάν που φαίνεται να είναι εντελώς δυσδιάκριτη ακόμη και τις μυστικές υπηρεσίες των μεγαλυτέρων χωρών του κόσμου.

Περισσότερα για το ιστορικό κίνημα των Κιζιλμπάσηδων και την παρουσία του σήμερα θα βρείτε εδώ:

Υπάρχουν ακόμη Κιζιλμπάσηδες;

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/03/υπάρχουν-ακόμη-κιζιλμπάσηδες/

Αλεβίδες, Μπεκτασήδες, Κιζιλμπάσηδες κι η Τουρκία σήμερα

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/04/αλεβίδες-μπεκτασήδες-κιζιλμπάσηδες/

Τουρκία, Ιράν, Κιζιλμπάσηδες, Κασκάι: Υπόγεια Κυκλώματα ανάμεσα στις Δύο Χώρες

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/05/τουρκία-ιράν-κιζιλμπάσηδες-κασκάι-υπ/

Κασκάι: η Μουσική, τα Ήθη και τα Έθιμα τους, οι Μεταναστεύσεις τους στα βουνά του Νότιου Ζάγρου — Ιράν

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/09/κασκάι-η-μουσική-τα-ήθη-και-τα-έθιμα-το/

Προσθέτω την διευκρίνιση (επειδή φίλοι με ερώτησαν ήδη) ότι δεν πρέπει να συσχετίζει κανείς τους Χαζάρα του Αφγανιστάν με τους Ασκενάζι Χαζάρους που ζούσαν και ζουν στα βόρεια ακρογιάλια της Κασπίας και προσποιούμενοι τους Ιουδαίους δημιούργησαν το σιωνιστικό κίνημα και έστησαν στην Παλαιστίνη το ψευτοκράτος Ισραήλ.

Στην συνέχεια μπορείτε να δείτε ένα βίντεο, να ακούεστε ένα τραγούδι σε χαζαράτζι (την γλώσσα των Χαζάρα), και να διαβάσετε επιλεγμένα άρθρα ιστορικού κι εθνογραφικού περιεχομένου αναφορικά με τους Χαζάρα.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Хазарейцы — Афганистан: тюркская шиитская нация против американцев, англичан, саудовцев и талибов

https://www.ok.ru/video/1509294475885

Περισσότερα:

Οι τουρκομογγολικής καταγωγής Χαζάρα είναι Σιίτες Κιζιλμπάσηδες που προσαρτήθηκαν στο ψευτοκράτος ‘Αφγανιστάν’ μόνον στις αρχές του 1900 και μετά από πολύ αίμα. Και στάθηκαν πάντοτε ενάντια στους Παστούνους ισλαμιστές Ταλιμπάν που ΗΠΑ, Αγγλία, Ισραήλ, Σαουδική Αραβία και Πακιστάν έχουν χρηματοδοτήσει από το 1980.

The Hazaras (Persian: هزاره; Hazaragi: آزره) are an ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Hazarajat in central Afghanistan. They speak the Hazaragi variant of Dari, one of the two official languages of Afghanistan. They are the third-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, also making up a significant minority group in the neighboring Pakistan, with a population of between 650,000–900,000, largely living in the region of Quetta.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazaras

Самоназвание хазарейцев — хезаре. Слово хезар в иранских языках означает «тысяча». По всей видимости, костяк этого народа составили воины, оставленные чингизидами после завоевания Афганистана в 1221–1223 гг.

По мнению Л. Темирханова, «хазарейцы — народ, сформировавшийся в результате синтеза монгольских и таджикских элементов».

Монгольские воины охранных гарнизонов-тысяч, в результате длительного проживания в Афганистане смешались с местными ираноязычными народами, переняв их язык.

Ученые считают, что язык хазарейцев является диалектом старотаджикского языка (хазараги) с некоторой долей монгольских и тюркских слов. Эту долю монголизмов и тюркизмов исследователи определяют в 10 %.

По мере ослабления Монгольской империи, хазарейцев все сильнее вытесняли из благодатных долин северо-востока. В результате, хазарейцы оказались зажатыми в центральных, сплошь горно-каменистых частях Афганистана. Хазарейцы ведут кочевой или полукочевой образ жизни. Кочевники живут в шалашах, покрытых войлоком. Основная же масса народа проживает крупными родовыми поселениями по склонам гор. Эти селения обнесены глинобитными стенами со сторожевыми башнями по четырем углам. Богатые жилища напоминают монгольские юрты, бедные живут в глинобитных хижинах, крытых соломой.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Хазарейцы

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Hazara — Afghanistan: a Turkic Shia Nation against Americans, English, Saudis and Taliban

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240304

Περισσότερα:

Οι τουρκομογγολικής καταγωγής Χαζάρα είναι Σιίτες Κιζιλμπάσηδες που προσαρτήθηκαν στο ψευτοκράτος ‘Αφγανιστάν’ μόνον στις αρχές του 1900 και μετά από πολύ αίμα. Και στάθηκαν πάντοτε ενάντια στους Παστούνους ισλαμιστές Ταλιμπάν που ΗΠΑ, Αγγλία, Ισραήλ, Σαουδική Αραβία και Πακιστάν έχουν χρηματοδοτήσει από το 1980.

Хазаре́йцы — ираноязычные шииты монгольского и тюркского происхождения, населяющие центральный Афганистан (8–10 % от общей численности населения страны).

Самоназвание хазарейцев — хезаре. Слово хезар в иранских языках означает «тысяча». По всей видимости, костяк этого народа составили воины, оставленные чингизидами после завоевания Афганистана в 1221–1223 гг.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Хазарейцы

Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire in the early 16th century, records the name Hazara in his autobiography. He referred to the populace of a region called Hazaristan, located west of the Kabulistan region, east of Ghor, and north of Ghazni.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazaras

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Χαζάρα-Αφγανιστάν: ένα Τουρκικό Σιιτικό Έθνος ενάντια σε Άγγλους, Αμερικανούς, Σαουδάραβες, Ταλιμπάν

Περισσότερα:

Οι τουρκομογγολικής καταγωγής Χαζάρα είναι Σιίτες Κιζιλμπάσηδες που προσαρτήθηκαν στο ψευτοκράτος ‘Αφγανιστάν’ μόνον στις αρχές του 1900 και μετά από πολύ αίμα. Και στάθηκαν πάντοτε ενάντια στους Παστούνους ισλαμιστές Ταλιμπάν που ΗΠΑ, Αγγλία, Ισραήλ, Σαουδική Αραβία και Πακιστάν έχουν χρηματοδοτήσει από το 1980.

The origins of the Hazara have not been fully reconstructed. Significant inner Asian descent — in historical context, Turkic and Mongol — is probable because their physical attributes, facial bone structures and parts of their culture and language resemble those of Mongolians and Central Asian Turks.

Genetic analysis of the Hazara indicate partial Mongolian ancestry. Invading Mongols and Turco-Mongols mixed with the local Iranian population, forming a distinct group. For example, Nikudari Mongols settled in what is now Afghanistan and mixed with the native populations.

A second wave of mostly Chagatai Mongols came from Central Asia and was followed by other Mongolic groups, associated with the Ilkhanate and the Timurids, all of whom settled in Hazarajat and mixed with the local population, forming a distinct group.

The Hazara identity in Afghanistan is believed by many to have originated in the aftermath of the 1221 Siege of Bamyan. The first mention of Hazara is made by Babur in the early 16th century and later by the court historians of Shah Abbas of the Safavid dynasty. It is reported that they embraced Shia Islam between the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century, during the Safavid period.

Hazara men along with tribes of other ethnic groups had been recruited and added to the army of Ahmad Shah Durrani in the 18th century. Some claim that in the mid‑18th century Hazara were forced out of Helmand and the Arghandab District of Kandahar Province.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazaras

The giant Buddha statues had long been central to the identity of the Hazara community. Although not built by the Hazaras themselves, who only came to have an ethnolinguistic identity based in the region some centuries later, they have their own myths associated with the statues, unrelated to Buddhism. In Hazara folklore, the statues are of a star-crossed couple Salsal and Shahmama, whose doomed love ends tragically in both their deaths. The two remain forever separated, petrified in stone, looking across the Bamyan valley.

https://minorityrights.org/minorities/hazaras/

==============================

Διαβάστε:

Hazāra

Hazāra: the third largest ethnic group of Afghanistan, after the Pashtuns and the Tājiks, who represent nearly a fifth of the total population. Their name most probably derives from the Persian word hazār, which means “thousand,” and may be the translation of the Mongol word ming or minggan, a tribal-military unit of 1000 soldiers of the Mongol army at the time of Gen-ghis Khan (Bacon, 1958, p. 4; Schurmann, p. 115; Poladi, p. 22; Mousavi, pp. 23–25). The term hazār(a) could have replaced ming in what is today Afghanistan, and has thus come to designate a specific group of people. Such an evolution may be witnessed also in the district of Hazāra, north of Islamabad (Pakistan), which takes its name from troops based in the region during the Timurid period.

The Hazāras speak a Persian dialect with many Turkish and some Mongolian words. They originally occupied the central part of the country, a mountainous zone called the Hazārajāt.

Though some inhabitants of the eastern fringe of the region are Sunnis (Ḡorband Valley) or Ismaʿilis (Ka-yān, Šibar), most Hazāras — unlike the majority of the Afghan population — are Twelver Shiʿites, a factor which has contributed to their political and socio-economic marginalization. The history of the Hazāras is marked by several wars and forced displacements.

Many of them fled from the Hazārajāt at the end of the 19th century, when Amir ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan subjugated the region; they settled in Quetta (then in British India, today in Pakistan) and around Mašhad. Driven by poverty, the Hazāras have migrated throughout the 20th century. Many went to the cities, especially to Kabul but also to Mazār-e Šarif and Herat, while others traveled to Pakistan or to Iran in search of employment.

This trend dramatically increased after the communist coup of April 1978 and the Soviet intervention in 1979.

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hazara-1

— — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Hazāra i. Historical geography of Hazārajāt

Hazārajāt, the homeland of the Hazāras, lies in the central highlands of Afghanistan, among the Kuh-e Bābā mountains and the western extremities of the Hindu Kush (q.v.). Its boundaries have historically been inexact and shifting, and in some respects Hazārajāt denotes an ethnic and religious zone rather than a geographical one–that of Afghanistan’s Turko-Mongol Shiʿites.

Its physical boundaries, however, are roughly marked by the Bā-miān Basin to the north, the headwaters of the Helmand River (q.v.) to the south, Firuzkuh to the west, and the Salang Pass to the east. The regional terrain is very mountainous and extends to the Safid Kuh and the Siāh Kuh mountains, where the highest peaks are between 15,000 to 17,000 feet.

Both sides of the Kuh-e Bābā range contain a succession of valleys. The north face of the range descends steeply, merging into low foothills and short semi-arid plains, while the south face stretches towards the Helmand Valley and the mountainous district of Besud (Fayż-Moḥammad, III; Thesiger, 1955, p. 313).

A series of mountain passes (kotal) extend along the eastern edge of the Hazārajāt, of which the Salang is blocked by snow for six months of the year or more, while the Šebar, at a lower elevation, is similarly snowed in for two months (Humlum, p. 64). In the spring and summer, the Kuh-e Bābā range accounts for some of Afghanistan’s greenest pastures.

A number of the country’s rivers, including the Helmand, Harirud, Kābul, Morḡāb, and Panjao flow from the Hazārajāt (Mostawfi, tr. Le Strange, p. 212). Natural lakes and caves are also found in the Hazārajāt, many in the environs of Bāmiān (q.v.), and these sites have become the subject of legends and folktales told by the Hazāras about the geography and history of their homeland. In some cases, these natural landmarks are attributed to the works of ʿAli ebn Abi Ṭāleb (Mousavi, p. 71).

In Ferdowsi’s Šāh-nāma, the Hazārajāt is referred to as Barbarestān, an independent region in Turān. The Arab geographer Maqdesi knew the region as Ḡarj al-šahr–Ḡarj meaning “mountain” in the local dialect–an area ruled by chiefs. In the later Middle Ages the region was called Ḡarjestān, though the exact location of its main cities was still unknown (Le Strange, tr., 1919, pp. 415–16; see also Mousavi, p. 39).

According to the 10th-century Persian geographical text Ḥodud al-ʿālam (ed. M. Sotuda, Tehran, 1961; q.v.), the area was “entirely mountainous” and its people were “herdsmen and farmers,” cultivating land, which was partly non-irrigated (lalmi) and partly irrigated (ābi; Ḥodud al-ʿālam, p. 105).

The Hazārajāt was then considered part of the larger geographic region of Khurasan (Kušān), the porous boundaries of which encompassed the vast region between the Caspian Sea and the Oxus River (Āmu Daryā; q.v.), thus including much of what is today northern Iran and Afghanistan.

Northwestern Hazārajāt encompasses the district of Ḡor, long known for its mountain fortresses. The 10th-century geographer Estaḵri wrote that mountainous Ḡor was “the only region surrounded on all sides by Islamic territories and yet inhabited by infidels” (Barthold, p. 51). Ebn Ḥawqal described Ḡor as a mountainous country full of mines and running streams (Ebn Ḥawqal, tr. Kramers and Wiet, II, pp. 429–30).

Ḡor’s rivers, cultivated fields, and pastures were praised by Edrisi, who surmised that the province’s boundaries were Herat, Juz-jān, Qarawāt, and Ḡarjestān (tr. Amedee Jaubert, p. 458). The long resistance of the inhabitants of Ḡor to the adoption of Islam provides an indication of the region’s inaccessibility; according to some travelers, the entire region is comparable to a fortress raised in the upper Central Asian highlands: from every approach, tall and steep mountains have to be traversed to reach there. The language of the inhabitants of Ḡor differed so much from that of the people of the plains, that communication between the two required interpreters (Barthold, p. 52).

The Bāmiān Basin, the northeastern part of the Hazāra-jāt, is the site of ancient Bāmiān, a center of Buddhism and a key caravanserai on the Silk Road. The town is situated at a height of 7,500 feet and surrounded by the Hindu Kush to the north and Kuh-e Bābā to the south. Ebn Ḥawqal referred to Bāmiān as “the cold part of Khurasan,” where winters are reportedly severe (Ebn Ḥawqal, p. 227). Bāmiān is famous for the two giant Buddhas carved into its sandstone cliffs, which stood at 165 and 114 feet tall, respectively, until they were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

It was not until the rule of the Ghaznavid dynasty in the 11th century that Islam was established in Bāmiān, Ḡor, and the rest of the Hazārajāt. According to Ḥamd-Allāh Mostawfi, at the time of the Mongol invasions Prince Mutukin, the son of Jaghatay Khan, was killed during the siege of Bāmiān. To avenge his grandson’s death, “Chingiz Khan ordered Bāmiān and its people to be laid in ruins, renaming the place Mav Baliq (“Bad Town” in Mongolian) and commanding that no one should ever build or settle there” (tr. Le Strange, p. 152)

The subjugation of the Hazārajāt, the mountain fortresses of Ḡor in particular, proved difficult for the Mongols after their conquest of the region, and ultimately Mongol military detachments left behind in the region “adopted the language of the vanquished” (Barthold, p. 82). During the late 14th century, Timur’s armies made expeditions into the Hazārajāt, but after his death the Hazāras were once again free in their mountains (Ferrier, p. 221).

In the Mongol period, most Hazāras were pastoralists who lived in yurts and whose language was Moḡol. By the early sixteenth century however, they were living in fortified villages (qalaʿ), speaking a Persian dialect, and farming the land to produce their own grains in the high steppes. They continued to keep flocks however, and some Hazāras on the more arid northern slopes of the Kuh-e Bābā remained nomadic, migrating between yeilaq, or highland summer pastures, and qishlaq, or lowland winter pastures (Humlum, p. 87).

It is probable that the Hazāras were mostly Sunnis who converted to Shiʿism in the Safavid era, though some have suggested that traces of Shiʿism in the region can be dated back to at least the Ilkhanid period. Most are Twelver Shiʿis, but there also exist Ismaʿili, Zaidi, and Sunni Hazāras (Mousavi, pp. 73–76).

In the 18th and 19th centuries, as a sense of “Afghan-ness” developed among the Sunnite Pashtuns, the Shiʿite Hazāra tribes began to cling together (Canfield, p. 3). Once the Ḡilzi (q.v.) Afghans became independent of the Safavids in the 1720s, Pashtun nomads (kuči, ilat) began to migrate into the pastures of Hazārajāt, pushing the Hazāras westward (Raverty, p. 35).

It has been suggested that in the nineteenth century there was an emerging awareness of ethnic and religious differences among the population of Kabul. This brought about divisions along “confessional lines” that became reflected in new “spatial boundaries” (Noelle, p. 22).

During the reign of Dōst Moḥammad Khan (q.v.; r. 1242–55/1826–39, 1259–79/1842–63), Mir Yazdānbaḵš, a diligent chief of the Besud Hazāras, consolidated many of the Hazāra tribes and the districts they controlled. Mir Yazdānbaḵš collected revenues and safeguarded caravans (qāfela) traveling on the Ḥājigak route through Bā-miān to Kabul from Shaikh ʿAli and Besud bandits. The consolidation of the Hazārajāt thus increasingly made the region and its inhabitants a threat to the Durrani state based in Kabul (Masson, II, p. 296).

Until the late 19th century, the Hazārajāt remained independent and only the authority of local leaders, ḵāns or mirs, was obeyed (Barthold, pp. 82–83). Joseph Pierre Ferrier, a French author who supposedly traveled through the region in the mid-nineteenth century, described the inhabitants settled in the mountains near the rivers Balkh and Ḵolm in an orientalist vein, casting the Hazāras as savage criminals:

“The Hazāra population is ungovernable, and has no occupation but pillage. They will pillage and pillage only, and plunder from camp to camp” (Ferrier, pp. 219–20). Subsequent British travelers doubted whether Ferrier had ever actually left Herat to venture into Afghanistan’s central mountains and have suggested that his accounts of the region were based on hearsay, especially since very few people dared then to enter the Hazārajāt; even Pashtun nomads would not take their flocks to graze there, and few caravans would pass through (Ferdinand, p. 18).

During the Second Anglo-Afghan War, Colonel T. H. Holdich of the Indian Survey Department referred to the Hazārajāt as “great unknown highlands” (Holdich, p. 41). And for the next few years, neither the Survey nor the Indian Intelligence Department succeeded in obtaining any trustworthy information on the routes between Herat and Kabul through the Hazārajāt (A. C. Yate, pp. 147–48).

In fact, the region remained largely unmapped in the modern sense until the work of the Afghan Boundary Commission between 1884 and 1886. The Commission, which was set up following Russia’s annexation of the Tekke Turkman stronghold of Marv, was a joint Anglo-Russian effort to establish the northern borders of Afghanistan. The Commission was a massive traveling survey, consisting of thirteen hundred men and two thousand animals. It strained local economies and became very unpopular among the people of Khurasan.

Various members of the Afghan Boundary Commission were able to gather information that brought the geography of remote regions such as the Hazārajāt further under state surveillance. In November 1884, the Commission crossed over the Kuh-e Bābā Mountains by the Čašma Sabz Pass.

General Peter Lumsden and Major C. E. Yate, who surveyed the tracts between Herat and the Oxus, visited the Qalaʿ-e Naw Hazāras in the Paropamisus mountain range, to the east of the Jamšidis of Kušk. Noting surviving evidence of terraced cultivation in times past, both described the northern Hazāras as semi-nomadic with large flocks of sheep and black cattle.

They possessed an “inexhaustible supply of grass, the hills around being covered knee-deep with a luxuriant crop of pure rye” (C. E. Yate, p. 9). Yate noted clusters of kebetkas, or the summer dwellings of the Qalaʿ-e Naw Hazāras on the hillsides, and described “flocks and herds grazing in all directions” (C. E. Yate, pp. 7–8; see also Lumsden, pp. 562–63).

The travels of Captains P. J. Maitland and M. G. Talbot from Herat, through Obeh and Bāmīan, to Balkh, during the autumn and winter of 1885, explored the Hazār-ajāt proper. Maitland and Talbot found the entire length of the road between Herat and Bāmīan difficult to traverse. They reported that the valleys of the Hazārajāt were well-cultivated and noted “a constant stream of people migrating from the country around Kabul, on account of the scarcity in the Afghan capital” (“Captain Maitlands and Captain Talbot’s Journeys in Afghanistan,” p. 103).

As a result of the expedition, parts of the Hazārajāt were “surveyed on one-eighth inch scale” and thus made to fit into the mapped order of modern nation-states (ibid., pp. 105–07; Anderson, pp. 170–78). More thought and attention was put into demarcating the definite borders of modern nations than ever before, which entailed great difficulties in frontier regions such as the Hazārajāt.

The geographical reach of the authority of the Afghan state was extended into the Hazārajāt during the reign of ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan (1880–1901). Caught between the strategic interests of foreign powers and disappointed by the demarcation of the Durand Line (1893) in southern Afghanistan, which cut into Pashtun territory, he set out to bring the northern peripheries of the country more firmly under his control.

This policy had disastrous consequences for the Hazārajāt, whose inhabitants were singled out by ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan’s regime as particularly troublesome: “The Hazāra people had been for centuries past the terror of the rulers of Kabul” (Munshi, ed., p. 276).

Later in the early 1890s, the tribes of the Hazārajāt were taxed and conscripted, while thousands were massacred. Pashtun nomads (kučis) were moved into the Hazārajāt, where they overran Hazāra farmlands and pastures (Mousavi, p. 95). Increasingly during summers, Pashtun nomads would camp in large numbers in the Hazārajāt highlands.

In the 1920s the ancient Šebar pass road which leads through Bāmiān and east to the Panjšir Valley was paved for lorries, and it remained the busiest road across the Hindu Kush until the building of the Salang tunnel in 1964 and the opening of a winter route. A paved road also has been built through the central mountains and the upper Harirud Valley to Herat. The Hazārajāt became increasingly depopulated as Hazāras migrated to cities and to surrounding countries, where they became laborers and undertook the hardest and lowest-paid work.

In 1979, there were reportedly one and a half million Hazāras in the Hazārajāt and Kabul (Rubin, p. 26). As the Afghan state weakened, uprisings broke out in the Hazārajāt, freeing the region from state rule for the first time since the death of Amir ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān. Under the inspiration of the Islamic Revolution, various Hazāra-Shiʿi resistance groups were formed in Iran, including Naṣr (Victory) and Sepāh-e Pāsdārān (Troops of the Revolutionary Guards), with some being “committed to the idea of a separate Hazāra national identity”(Rubin, pp. 186, 191, 223).

During the war with the Soviets, most of the Hazārajāt was unoccupied and free of Soviet or state presence. The region became ruled once again by local leaders, or mirs, and a new stratum of young radical Shiʿi commanders. Economic conditions are reported to have improved in the Hazārajāt during the war, when Pashtun Kučisstopped grazing their flocks in Hazāra pastures and fields (Rubin, p. 246).

In recent times under the regime of the Taliban, the Hazārajāt again came under siege, as ethnic and sectarian violence devastated the region. In the spring of 1997, a revolt broke out among Hazāras in Mazār-e Šarif who refused to be disarmed by the Taliban. In the subsequent fighting, 600 Taliban were killed as they tried to flee from the city (Rashid, p. 58). The following year, in retaliation, the Taliban instituted genocidal policies reminiscent of Amir ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan’s time.

In 1998, an estimated five to six thousand Hazāras were massacred, as the Taliban tried to “cleanse” the north of Shiʿites (Rashid, pp. 67–74). At that time, the Hazārajāt was a vernacular region that did not exist on the official map of Afghanistan; the area was divided between the administrative provinces of Bāmiān, Ḡor, Wardak, Ḡazni, Oruzgān, Juzjān, and Samangān, with the Hazāras being a minority in each (Rubin, p. 246).

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hazara-i

— — — — — — — — — — — — -

ii. History

The Origins and the Early History

The origins of the Hazāras are uncertain and much debated among scholars (see Bacon, 1951, 1963; Ferdinand, 1959; Schurmann, pp. 110–58; Gawecki, 1980; Poladi, pp. 1–29; Mousavi, pp. 19–43). Among the Hazāras themselves, three main theories exist: they are of Mongolian or Turko-Mongolian descent (sometimes, they are even considered to be the direct heirs of Genghis Khan’s armies); they are the autochthones of the area, representing a stock of population preceding the invasions by Indo-European speaking people (2000–1500 B.C.E.); they are of mixed race as a result of several waves of migration.

The Mongol contribution seems difficult to deny considering the common physical appearance of the Hazāras, even if their features are actually very variable.

The term hazāra first appeared at the beginning of the 16th century in the memoirs of Babur (1987), the founder of the Mughal dynasty in India. He used it several times to designate people living in different regions, like the Rustā-hazāra of Badaḵšān (Babur, p. 196) or the Turkman Hazāras, a warlike tribe he fought in 911/1506 (Babur, pp. 251–53), and more generally the inhabitants of the mountainous area situated west of Kabul, as far as the historical provinces of Ḡor and Ḡazni (q.v.). Part of their population spoke a Mongolian language (Babur, pp. 200, 207, 214, 218, 221).

Babur mentions not only the Hazāras but also the Nik-dārā or Niku-dārā, a term by which he designates people of Mongolian origin (Babur, p. 200). He also uses the word aymāq to refer to Mongolian tribes (Babur, pp. 196, 207, 221). The terminology does not seem to be fully defined and, although the term hazāra had different referents, it seems to have already served to designate a population with strong Mongolian elements living in the area known today as the Hazārajāt.

Bacon (1951, 1958) argues that the Hazāras are the descendants of Chaghatay Mongols who came from Transoxania to the highlands of central Afghanistan in successive waves between 626/1229 and 850/1447. Schurmann (1962) refutes the view that the Hazāras are from a pure Mongolian descent. For him, the Niku-dāri Mongols who settled on the eastern fringes of Persia, combined with the local population who spoke various Iranian languages, have played the most important role in the ethnogenesis of the Hazāras.

Kakar (1973) considers both theories as plausible: a first contingent of Chaghatay Mongols may have arrived in the Hazārajāt from Central Asia, to be joined over time by later migrating peoples (other Mongols or Turko-Mongols, Ilkhanids driven out of Persia, Timurids), and mixed with the local population of the area who were of Persian origin. In any case, the Hazāras formed a distinct group occupying what corresponds approximately to their present habitat at least since the beginning of the 16th century C.E. Under the influence of the Safavids of Iran, they converted to Shiʿism between the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century (Mousavi, 1998).

Without taking side in this controversy (see also Ferdinand, 1959, 1964; Mousavi, pp. 28–31), it seems probable historically that the origins of the Hazāras lie with the Mongolian and Turkish groups which progressively penetrated the infertile mountainous region situated between Persia, Central Asia, and India between the 13th and the 15th centuries, mixed with the local population and adopted their language.

It must also be pointed out that Turko-Mongolian people, like the Hephtalites (5th and 6th centuries), were already present in what is today Afghanistan and therefore may also have played a role in the ethnogenesis of the Hazāras (Mousavi, p. 38).

Nevertheless, Fredrik Barth’s work on ethnicity (1969) has made it evident that group identity is not defined by objective traits and does not follow from a common origin or even a common culture. It is, rather, the result of a constant process of social interaction by which a boundary is created and maintained in an enduring way.

There are many Middle Eastern examples where distinct groups were formed by people of heterogeneous origins in marginal regions following a continuing process of inclusion and exclusion and of resistance to central powers (Canfield, 1973a, pp. 10–12 and 1973b, pp. 1511–13).

In the case of the Hazāras, the feeling of belonging to one group does not proceed from a supposed Mongolian origin, but from a process of marginalization which started several centuries ago. As mentioned already, the term hazārahas been used to designate a heterogeneous group, including some Sunni groups (for instance in the district of Rustāq, province of Taḵar, or the district of Nahrin, province of Baḡlān). It seems to refer as much to a social position as to a common historical origin.

The Subjugation of the Hazāras by Amir ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan (r. 1880–1901)

For most of the period since the 16th century, the Hazāras have evaded the control of the powerful regional empires (Safavids in Iran, Uzbeks in Central Asia, Mughals in India). But since the middle of the 18th century and the formation of modern Afghanistan, the Hazāras have faced continual pressure from the Pashtuns which has forced them to abandon vast territories in the Helmand and Arḡandāb basins.

Having visited the area in the 1840s, Ferrier (1857, pp. 220–21) highlighted the hos-tility between the Hazāras and the Pashtuns, who would hesitate to venture into the Hazārajāt. During the second reign of Amir Dōst-Moḥammad Khan (q.v.; 1259–79/1842–63), the administration in Kabul collected taxes in Bāmiān (q.v.) and certain peripheral areas of the Hazārajāt (Noelle, 1997). But only his grandson, ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan, was able to subjugate the Hazāras after a difficult war and put to an end Hazāra autonomy.

ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan was brought to power just after the Second Anglo-Afghan war (1878–79), concluded by the Treaty of Gandomak: the territorial integrity of Afghanistan was guaranteed, but the British gained control over its foreign policy. The new amir devoted his reign to the reinforcement of central power and the unification of the kingdom.

He was an autocrat and rapidly faced several revolts within his own family as well as the Ḡilzi (q.v.) and Šinwāri insurrections. Once he had consolidated his throne, he set out to conquer the virtually independent Hazārajāt. In the face of strong resistance, he launched a series of campaigns marked by a sectarian and ethnic polarization and many atrocities.

The conflict could have been caused by several major factors (see Mousavi, pp. 115–20), including the following: opposite tendencies towards centralization and decentralization, which led to tensions between the central government and the Hazāra tribal leaders; the amir’s desire to reduce the autonomy of powerful tribal chiefs and marginal groups, such as the Hazāras, who represented a threat for security and communications in the state; long-lasting tribal feuds and struggles between competing challengers for central power (ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān spared large parts of southern Hazārajāt, once his authority had been accepted there, and waged war on the Hazāra leaders who supported the previous ruler of Afghanistan, his uncle Šēr-ʿAli).

When ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān’s cousin, Moḥammad-Esḥāq, the governor of Mazār-e Šarif, rebelled against him, several of the Šayḵ ʿAli Hazāra tribal leaders joined the revolt. ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān used the sectarian division among the Šayḵ ʿAli tribe (some of whom are Sunnis) to crush this first uprising in 1888. During the following years, he extended his control over increasingly large parts of the Hazārajāt, imposing governmental taxes and dispatching Pashtun administrators, who committed several kinds of abuses: they disarmed people and looted villages, imprisoned, and sometimes executed, tribal chiefs and elders, and appropriated the best pastures in order to give them to Pashtun nomads.

A strong Hazāra uprising began in the spring of 1892; according to Mousavi: “The actual trigger for the first rebellion was the assault by thirty-three Afghan soldiers on the wife of a Pahlawān Hazāra. The soldiers, who had entered the house under the pretext of searching for arms, tied the man up and assaulted his wife in front of him.

The families of both the man and his wife, deciding that death was one hundred times better than such humiliation, killed the soldiers involved and attacked the local garrison, from whence they recovered their confiscated arms” (Mousavi, pp. 124–25). Important tribal leaders, such as Moḥammad-ʿAẓim Beg, from Dāy Zangi, a former supporter of ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan, joined the rebellion which soon spread throughout the Hazārajāt.

Worried about the direction taken by the events, the amir declared jihad against the Shiʿites, and raised a powerful army of some 30,000–40,000 governmental troops, 10,000 mounted troops and some 100,000 civilians (in particular many Pashtun nomads) assisted by British military advisers (Mousavi, p. 126, referring to Fayż-Moḥammad, 1912–14 and Timurkhanov, 1980).

In August 1892, Urozgān, the main center of the rebellion, was captured, and the local population massacred: “thousands of Hazara men, women, and children were sold as slaves in the markets of Kabul and Qandahar, while numerous towers of human heads were made from the defeated rebels as a warning to others who might challenge the rule of the Amir” (Mousavi, p. 126). The repression was so harsh and the Hazāras were treated so unjustly that a second uprising started in early 1893.

The rebels took by surprise the governmental forces and quickly regained control over most of the Hazārajāt. Despite the fact they were deeply divided, they resisted the counteroffensive by the amir’s troops, and it was only in the summer of 1893, after months of fierce fighting, shortage of food, and the prospect of famine, that Hazāra forces suffered a resounding defeat, though skirmishes continued until the end of the year.

Governmental troops did not refrain from committing atrocities, including the killing and deportation of the populations of entire villages.

ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān’s strategy to crush the Hazāra uprising fostered hatred between the different groups. The conflict caused a deep ethnic and religious polarization (Pashtuns vs. Hazāras, Sunnis vs. Shiʿites) and led to the forced displacement of populations on a massive scale; lands were confiscated and the inhabitants of entire regions fled or were expelled (especially in the province of Urozgān and the district of Dāy Čōpān, province of Zābul; Kakar, 1973, 1979; Poladi, pp. 229–34, 245–55; Mousavi, pp. 136–38).

Basing this statement on the work of Timurkhanov (1980), Mousavi (p. 129) estimates that 15,000 Hazāra families escaped from their land and settled in Afghan Turkistan, near Mašhad (where they are called Barbaris), in Quetta (then in British India, today in Pakistan), and even in Central Asia. He estimates that more than half of the entire Hazāra population was massacred or driven out of their villages (Mousavi, p. 136).

It is difficult to verify such an estimate, but the memory of the conquest of the Hazārajāt by ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan certainly remains vivid among the Hazāras themselves, and has heavily influenced their relations with the Afghan state throughout the 20th century. While ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān may have achieved the political unification of the country, he failed nonetheless to incorporate all segments of Afghan society.

The 20th Century

ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Khan’s son and successor, Amir Ḥabib-Allāh (q.v.), granted a general amnesty to all who had been exiled by his father. But the gulf lying between the Afghan government and the Hazāra population was too deep; and, during most of the 20th century, the Hazāras have faced severe social, economic and political discrimination.

British travelers Moorcroft and Trebeck (II, p. 384) mentioned the presence of Pashtun nomads in the area of Behsud as early as 1824. Even if Pashtuns had pastured in the Hazārajāt before its conquest by Amir ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān, it was this event that gave them their preeminent position there. They are known to have seized the best grazing land for their flocks, but nomads are not only stockbreeders but traders as well.

By loaning money and selling manufactured goods, they were able to gain a further economic advantage over the sedentary Hazāras. Farmers were often obliged to surrender their property to their Pashtun creditors in order to reimburse their debts, and thus became mere tenants on their own lands (Ferdinand, 1962). In consequence, many impoverished Hazāra farmers were forced to migrate seasonally in search of employment to the main cities of Afghanistan, or those of Pakistan and Iran.

In spite of the general distrust the Hazāras felt towards the central government, most of them did not support the anti-Pashtun revolt in 1929 led by the Tājik adventurer Ḥabib-Allāh, known as Bačča-ye Saqqā (q.v.; McChesney, 1999).

However, local uprisings broke out sporadically in the Hazārajāt against government abuses, the most famous of which was led by the Hazāra rebel from Šahrestān, Ebrāhim Beg, popularly known as Bačča-Gāw-sawār (“son of the cow rider”), in the second half of the 1940s. He revolted against the introduction of a new tax imposed exclusively on the Hazāras, which was payable in cooking oil per head of animal (not only cows and sheep but also horses and donkeys, which do not produce milk for human consumption).

Pashtun nomads were not only exempted from taxes but even received financial allowances from the state administration. The rebels captured and killed several government officials. Confronted with such a violent reaction, the government sent a force to pacify the region and withdrew the tax. The exploits of bandits (yāḡi) who revolted against the state’s arbitrary treatment are told in popular tales, such as those of Yusof Beg, who is supposed to have evaded the police for nineteen years before finally being captured and executed (Edwards, pp. 208–11; Poladi, pp. 384–85, 396–97; Mousavi, p. 163).

All the events are kept alive in folk and revolutionary songs (Bindemann, 1988), in which Fayż-Moḥammad (the Hazāra secretary of ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān, who reported the bloody conquest of the Hazārajāt), ʿAbd-al-Ḵāleq (the young Hazāra who took part in a family and political feud between two Pashtun factions and murdered Nāder Shah in 1933), and Sayyed Esmāʿil Balḵi (an important Shiʿite religious leader who was imprisoned between 1949 to 1964) are all celebrated like heroic rebels against an oppressive power.

Hazāra identity is thus reinforced by the evocation of past injustices and protests against social exploitation and discrimination.

Since 1978: War and Exile

In the early 1970s, the Hazārajāt, like other parts of Afghanistan, faced a severe drought, which led to a shortage of food. It was the first step in the series of dramatic events which paved the way for the seizure of power by the Communists in 1978, many of whom were young, recently urbanized and detribalized people seeking social advancement. Within a few months, most of the country was in rebellion, and in 1979 the Soviet Union intervened militarily.

A bitter guerrilla war ensued over the next ten years between the Red Army and the predominantly Islamist Afghan resistance fighters, or mujahideen [mojāhedin], during which about 1.5 million Afghans died and millions more left the country. The Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and the fall of the Communist regime in 1992 led to an explosion of tensions and expressions of dissatisfaction.

While the 1980s were marked by the development of Islamist resistance parties, the 1990s were characterized by the rise of ethnic clashes, which were more a result, rather than a cause, of the civil war.

An accurate account and analysis of the war in the Hazārajāt between 1978 and 1992 may be found in Harpviken (1996; see also Roy, pp. 194–205). Relatively spared by the Soviet forces, the Hazārajāt was the scene of bitter internal conflicts during the 1980s.

The main competing parties involved during this decade were: the Tanẓim-e nasl-e naw-e Hazāra-moḡol, a party based in Quetta and inspired by Hazāra nationalists and secular intellectuals (some of whom were discreetly affiliated to Maoist movements like the Šoʿla-ye jāwid); the Šurā-ye enqelābi-e ettefāq, dominated by the traditional leaders (mirs, or tribal leaders, and sayyeds, or descendants of the Prophet); the Ḥarakat-e eslāmi, representing non-Hazāra Shiʿites, some sayyeds, and secular intellectuals under the guidance of Shaikh Āsef Moḥseni (a Shiʿite scholar from Kandahar); the Sāzmān-e naṣr and the Sepāh-e pāsdārān, who were competing Islamist parties backed by Iran and led by young pro-Khomeini militants.

It was the traditional leaders, the mirs and sayyeds, who led the uprising against the Communist regime as an allied force, and liberated the Hazārajāt from central control as early as 1979. In the following years, the sayyeds backed by the Islamists, turned against the secular forces, including the mirs as well as the intellectuals, and took control of most of the Hazārajāt. Between 1982 and 1984, after severe fighting, this group lost their position of dominance to the Islamists, who were strongly supported by Iran.

The Šurā-ye ettefāq was obliged to take refuge in its stronghold of the region of Nāwor. After the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, Hazāra leaders felt the necessity to bypass their antagonism in order to play a role on the national scene. The Islamist leaders shifted their discourse on ethnic identity in response to this development, and broadened their political legitimacy. This trend was marked by the creation of the Ḥezb-e waḥdat, a vast alliance joined by most of the former Hazāra resistance groups, with the notable exception of Ḥarakat-e eslāmi.

After the fall of Kabul in April 1992, deep tensions did not take long to appear between the different factions. While Ḥarakat-e eslāmi and most of the former Sepāh-e pāsdārān became closely linked with Rabbāni’s government, the majority of Ḥezb-e waḥdat (controlled by for-mer Sāzmān-e naṣr leaders) joined the opposition.

The Ḥezb-e waḥdat was obliged to beat a retreat from Kabul in March 1995, when their leader, ʿAbd-al-ʿAli Mazāri, was treacherously captured and killed by the Taliban (ṭālebān).

It was only after the capture of the Afghan capital by the Taliban in September 1996 that the different Hazāra factions were able to unite as part of the wider Northern Alliance, against this common enemy.

In spite of a fierce resistance, they were unable to prevent the fall of the Hazārajāt, which became totally surrounded and isolated from the outside world in September 1998.

The international intervention following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington has removed the Taliban regime from Afghanistan, but the situation is still very volatile.

In spite of all their internal conflicts during this time and the hardships of fighting and exile, war has paradoxically opened new doors to the Hazāras, who have in consequence undergone a process of political and economic empowerment.

Today, they have gained a role on the national scene they had never been able to reach since their incorporation into the Afghan state at the end of the 19th century.

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hazara-2

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

iii. Ethnography and Social Organization

Tribal Organization

Apart from the scholarly work of Elphinstone (1815) and the writings of diplomats, officers, and travelers of the 19th century (Burnes, 1834; Moorcroft and Trebeck, 1841; Masson, 1842; Ferrier, 1857), among the best sources on the Hazāra tribal system prior to 1892–93 are the reports of the Afghan Boundary Commission, in particular those of Lieutenant-Colonel Maitland (1891), who was a member of the mission in Afghanistan between 1884 and 1886.

He reported an oral tradition according to which the Hazāras were originally divided into eight tribes: Dāy Zangi, Dāy Kondi, Dāy Čōpān, Dāy Kalān (the modern Šayḵ ʿAli), Ḵatay, Behsud, Fōlādi, and Dahla (Maitland, p. 284). He added that the first five tribes are always mentioned, while any one of the last three is sometimes replaced by the Dāy Mirdād.

At the time of his visit, Maitland (p. 286) gave the following list of tribal and territorial divisions of the Hazāras: Behsud (region of Behsud, east of the Hazārajāt), Dāy Zangi (region of Dāy Zangi, to the north and northwest of the Hazārajāt, with Yak-awlang), Dāy Kondi (region of Dāy Kondi, west of the Hazārajāt), independent Hazāras (southeast and south of the Hazārajāt, in today’s province of Urozgān and nearby areas, including the Dāy Fōlādi, Dāy Čōpān, and Qalandar), Ḡazni Hazāras (Jā-ḡori, Moḥammad Ḵᵛāja, Čahār Dasta, Jaḡatu Hazāras), Šayḵ ʿAli Hazāras (northeast of the Hazārajāt, including Karam-ʿAli, Dāy Kalān, Karluq, ʿAli Jām, and Turkman Hazāras, some of whom are Sunnis), Hazāras of Bāmiān (only small sections are given, including the Tatars of Kahmard and Dō-āb), Hazāras scattered in Afghan Turkistan.

This list is heterogeneous, and several terms stand merely for a regional unit. It suffices to say that it would be misleading to present a fixed and definitive image of the main Hazāra tribes, as the affiliations are changing over time and the designations reflect the political situation.

Furthermore, the incorporation of the Hazārajāt into the Afghan state has disorganized the tribal system of the Hazāras considerably. As several scholars have remarked, previous tribal names — like Behsud, Dāy Kondi and Jāḡōri — tend today to become territorial designations (Schurmann, p. 121; Gawecki, 1986, p. 16). Lineages (ḵān(a)war) have kept their social relevance, but wider tribal affiliations are no longer the main way of self-identification.

Habitat and Land Use

In most of the Hazārajāt, settlements consist of small hamlets (qaria or āḡel); fortified farms (qalʿa) dominate in the south, while smaller houses and huts (čapari) are found towards the north. The basic territorial unit of social life in the Hazārajāt is the manṭeqa (literally “area, region”). In most of the region, these communities are made up of several descent groups — often, though not always, claiming a common ancestor — which are split into separate hamlets.

They have external kinship ties and maintain local solidarity with their neighbors (Monsutti, 2000a; 2002, pp. 111–66). In some areas of eastern Hazārajāt where non-irrigated agriculture dominates, factionalism may be expressed in the form of sectarian alignments between Twelver Shiʿites and Ismaʿilis (Canfield, 1973a and 1973b).

The Hazāras dwelling south of Kuh-e Bābā are mostly highland sedentary farmers. Those who live to the north (between Yak-awlang and Bāmiān) have a more pastoral economy. However, on the northern part of the Hazār-ajāt, high altitude settlements (aylāq) are distinguished from permanent villages situated in the valley (qešlāq). Irrigated land (zamin-e ābi) may be worked jointly by a group of brothers or even cousins (especially due to the fact that several male adults may have left), but it tends to be owned privately by an individual.

However, it may not be sold to strangers, and the members of the owner’s descent group have a pre-emptive right to it. Most grazing land (čarāgāh, zamin-e ʿalafčar) is held communally and used by the inhabitants of the same hamlet, or sometimes by the members of the same lineage. Many farmers cultivate land they do not own: they customarily keep a quarter of the crop and give three quarters to the landlord, who normally also provides the water and the seed.

Wheat is the main crop. Irrigated wheat may be classified into two groups: autumn wheat (gandom-e termāhi), which is sowed in autumn and harvested in summer, and is common in the south; and spring wheat (gandom-e bahāri), which has a shorter cycle (it is generally sowed in April and harvested just before the winter) and tends to be predominant in the higher and colder areas of the center and the north of the Hazārajāt. Non-irrigated wheat may also be found; it is considered to be of better quality but has a much smaller yield.

The economy of the Hazārajāt is not self-sufficient but depends on migration and remittance networks. These have been set up throughout the 20th century, but have played an increasingly important role since 1978.

Kinship and Marriage

The domestic group typically consists of a man, his wife, his sons as well as their spouses and children, and the unmarried daughters. The family’s heritage may sometimes be divided up even while the father is still alive, or it may remain as one whole even after his death. As long as there are no serious conflicts, brothers are reluctant to split up the heritage. There is actually no compelling rule on this matter.

Male and female roles are strongly differentiated. The public sphere is the domain of men, and the domestic one is the realm of women. Women take care of young children, cook for the household, and clean the house. They may have a small garden to tend and a few chickens. They weave and sew and, in some areas, make rugs and felt.

In a peasant family, men look after the sheep and goats and plow, sow and harvest, thresh and winnow the crops. Among both rural and urban people, a man must not stay at home during the day. War, however, has led women to take over many traditionally male duties, while men who have migrated abroad have had to learn to cook, sew, and do the laundry.

Hazāragi has a very rich kinship terminology (Heslot, 1984–85; Monsutti, 2002, pp. 407–11), and its social use is very flexible. Cooperation is not exclusively determined by kinship and lineage. There are multiple registers of solidarity, especially in the context of migration. Relationships of trust and rivalry overlap. Three social domains emerge: agnates; other collaterals, affines, and friends; external relations.

Patrilateral kinship determines the strongest level of solidarity but is also the arena of intense conflicts. It is structurally opposed to friendship and, to some degree, to matrilateral kinship and alliance, which are the domain of connivance, freedom of speech, and, very often, of trade partnership.

Because of their intensity, they are all distinct from the external relations with strangers, which are unpredictable and dominated by hostility. Face-to-face rivalry between patrilateral cousins differs markedly from the general distrust between strangers. Among the Hazāras — as in many parts of Afghanistan and the Middle East — relationships between close agnates are alternately dominated by solidarity or hostility.

Generally in Afghanistan, patrilateral kinship terms imply respect, but also rivalry, competition, and jealousy at a given generational level. They may even be characterized by avoidance behavior. Indeed, the main stakes and conflicts arise between the heirs of the same man, especially among sedentary farmers. They will, for instance, fight over land and water resources. Heavy obligations also imply acute tensions. Paradoxically, the circle of solidarity is also the most frequently violent.

Matrilateral kinship terminology does not imply the same degree of formalism, and interpersonal relations are often more affectionate between distant members of one’s lineage, matrilateral relatives and affines, than between close agnates. Cross cousins (bačča-ʿamma, or father’s sister’s son, and bačča-māmā, or mother’s broth-er’s son) represent a positive social sphere where solidarity and affection dominate relationships.

This feature may derive from the strong ties which exist between brother and sister. These are the persons of choice for borrowing money and for setting up a joint venture. Matrilateral parallel cousins (bačča-ḵāla, or mother’s sister’s son, or bola in Hazāragi) also play an important role. The relationships between bola (sons of two sisters) and bāja (husbands of two sisters) are symmetrical and affectionate, a light-hearted kind of classification of kinship.

They seem to be rarely the basis for building commercial partnerships, and their way of interaction has similarities with friendship. Another interesting term is ḵʷār-zāda (sister’s son or sister’s daughter) — or jeya, the term used in some places such as Šahrestān — which Hazāras tend to use for every man whose mother is from their own lineage, even if they are older (especially for the father’s sister’s children).

Schurmann (1962, p. 140) considers this to be a legacy of the Omaha terminology of the old Mongols. Marriage is considered an obligation, and divorce is rare and stigmatized. Polygamy is uncommon and occurs primarily when a man feels obliged to marry the widow of his dead brother. The general pattern is to marry kin, although families also try to diversify their social assets through marriage.

Marriage between patrilateral parallel cousins seem to be less common among the Hazāras than marriage between cross-cousins (Monsutti, 2002, pp. 139–42). In such a cultural context, cross-cousins, distant collaterals, and also affines are preferred to agnates for borrowing money and setting up commercial partnerships. Some long-term relationships, grounded in a common interest as well as friendship, have also been developed with members of other Afghan groups or with host societies (guides, transporters, smugglers, etc.), even if war and exile have generally deepened social fragmentation and distrust.

Social and Political Stratification

Hazāra society is stratified. The descendants of the Prophet, or sayyeds, form a sort of religious aristocracy, even if many of them are simple farmers. They receive external marks of respect, tend to practice endogamous marriages, and play an important role as mediators, relying on prestige rather than personal wealth.

The tribal chiefs, or mirs, were very powerful until the end of the 19th century, but their influence has been undermined during the 20th century by the increasing penetration of the central administration system, even if local communities are still dominated by the richest landlords. In today’s Hazārajāt, people use the term ḵān rather than mir for men whose influence is based on kinship, social capital, and personal wealth.

The village headmen (arbāb or malek), who work as intermediaries between their local communities and government officials, are often chosen from among the family elders (riš-safid,or muy-safid). Since 1978–79, all these leaders have lost part of their power to the commanders (qomāndān) of the resistance parties and the leaders of the militant religious groups formed in Iran (usually called šayḵān in the Hazārajāt). Hazāra society is thus facing a dramatic evolution and political roles follow increasingly new patterns (Roy, pp. 194–205; Harpviken; Monsutti, 2000a).

Religious Practices and Life-cycle Ceremonies

The great majority of Shiʿites in Afghanistan are Hazāras. David Edwards (1986, p. 204) has commented that “their practice of Islam was one that had little connection to scriptural traditions” and was characterized by “the development of an insular tradition focused on the person of ʿAli.” There are no real mosques in the Hazārajāt.

The religious life of the villages is centered on a build-ing called the membar (from menbar, the pulpit of a mosque), which fulfils the function of a prayer hall, meet-ing room, and guest room, and is sometimes used as a classroom as well. Isolated from the intellectual Shiʿite centers, Hazāra religious practice is dominated by reverence for saints (pirān), whose authority comes from their ability to transmit God’s blessing, and is expressed by visits to their shrines. Most of these saints were also sayyeds.

Village mullahs in the Hazārajāt receive the basic level of religious education required to enable them to at least teach children and lead the Friday prayers. Since 1978–79, an Iranian-type of clerical hierarchy has slowly emerged, introducing a new kind of religious leader: the young militant Islamist. Often born into a modest family, they challenge the authority of traditional practitioners and propose a more political conception of religion.

Besides the commemoration of the martyrdom of Imam Ḥosayn, the Prophet’s grandson through his daughter Fāṭema and his cousin ʿAli, which is the most important event in the religious calendar for the Hazāra Shiʿites, the community also observes the Persian New Year (nowruz), the fast of Ramażān, and the two main Muslim festivals, or ʿids (called locally ʿid-e qor-bān and ʿid-e ramażān).

Other major social and religious events are the various rites of passage which mark the life of each individual: birth, circumcision for the boys, marriage, and death (the Hazāras have very specific mourning songs).

The commemoration of the martyrdom of Ḥosayn ebn ʿAli is an event of central importance for all Shiʿites in the world. While it seems to have not been of major relevance among the Hazāras until the last decades of the 20th century, it has become increasingly significant since then.

This is because it has become part of a larger process of politicization, serving as an occasion to remember the injustice and violence that the Hazāra community too has suffered, as they see their own painful history reflected in the tragic fate of Imam Ḥosayn. Repressed under the Taliban regime, the most spectacular expressions of the commemoration of Mo-ḥarram are found in urban centers (Kabul and Mazār-e Šarif in Afghanistan, and Quetta in Pakistan), rather than the Hazārajāt.

At the beginning of the month of Moḥarram, flags (ʿalam) are put up on each side of the entrance of the religious centers, signaling a period of sorrow for the whole community, during which, for instance, no wedding is celebrated. Men wear black or green shirts and white pants as a sign of mourning, and women avoid dressing in elegant clothes.

All music is forbidden during this period except for dirges (nawḥa). Other activities are now suspended, as if time has stopped for the sake of the events organized to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Ḥosayn. If they have the means, many families take advantage of this period to organize meritorious meals for the needy and the pious (naḏr, or more specifically naḏr-e emām Ḥosayn), and every evening people gather to pray.

Specialists (ḏāker) invoke the name of God and narrate, day by day, the detailed unfolding of the events as they are reported by tradition, until reaching the paroxysm on the tenth day of the month of Moḥarram, the ʿĀšurā (q.v.), which is the anniversary of Ḥosayn’s death.

Groups of penitents (dasta) form a procession, some flagellating themselves with razor blades and chains. After three, seven, and fourteen days following the ʿĀšurā the Hazāras again commemorate Ḥosayn’s death but in a less spectacular and public way, and forty days later a new mourning ceremony takes place, the čelom (čehelom, lit. the “fortieth”).

The commemoration of Moḥarram can be seen to function as a kind of outlet for tensions and frustrations accumulated during the year; and, within the sermons (rawża), the sufferings endured by the Hazāras are constantly compared with those endured by Ḥosayn and his family.

For instance, the thirst which tortured the Imam’s companions when they were prevented from getting water from the Euphrates is compared with the blockade of the Hazārajāt by the Taliban between the summer of 1997 and the fall of 1998, and the profanation of Ḥosayn’s body is compared with the tragic end of ʿAbd-al-ʿAli Mazāri, the Hazāra leader captured and killed by the Taliban in March 1995.

More generally, the fate of the victims of Karbala is compared to the past and recent massacres suffered by the Hazāras (e.g., the slaughter of several hundred civilians in Afšār Minā, a district of Kabul, by troops allied to Aḥmad-Šāh Masʿud in January 1993, and the mass executions by the Taliban in Mazār-e Šarif in August 1998).

The Hazāras identify strongly with the suffering of Imam Ḥosayn, and also declare that they are ready to fight for him and for a return to justice. By mortifying themselves, they hope to expiate their sins and accelerate the coming of an era of justice. Sadness and mourning thus open a more positive perspective on the basis of the conviction that a better future will follow.

The ʿĀšurā, is thus not only the occasion to mourn the martyrdom of Imam Ḥosayn but also to declare oneself ready to seek revenge. In the conception that many Hazāras have of the end of time, there is a pronounced emphasis on revenge.

The Hidden Imam will come back then to punish the guilty and redress injustices. The world is corrupted, and the faithful must remain attentive to the sign of its destruction.

Migration and Remittance Networks

During the past 20 years, Afghanistan has been torn apart by war and civil strife, which have generated the largest refugee population in the world. Like most Afghan groups, the Hazāras fled in large numbers after the coup of April 1978 and the Soviet intervention in 1979.

Most of them went to one of the neighboring countries of Afghanistan. Migrants and refugees have thus come to overlap and can hardly be distinguished from each other. Their movements follow various patterns: thousands of farmers from the Hazārajāt migrate every winter to work in coal mines near Quetta for a few months, while young men migrate for longer periods to Iran to take on me-nial jobs.

During the last two decades, the Hazāras have formed very efficient migratory and economic networks, based on the dispersion of relatives in Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Each place has its own advantages and drawbacks. In Iran (especially in the big cities), it is relatively easy to find a job but almost impossible to settle down on a long-term basis with a family; on the other hand, in Quetta, Hazāras can move freely, but very few employment opportunities are available to them; however, in the Hazārajāt, social, political, and economic prospects are grim even if one’s family possesses its own property and farmland (Monsutti, 2000b, 2002).

Hazāra migrants and refugees in Iran cannot use the official banking system, since many of them are illegal workers and therefore unlikely to have any recognized documents as proof of identity. In any case, banks do not operate in the Hazārajāt itself. Therefore, when they wish to send their savings back to their families in Afghanistan, they must entrust their money to a businessman who specializes in remittances (known locally as a ḥawāla-dār).

Various actors are involved in a typical case of the ḥawāla (credit note) system, the three main ones being the migrant worker (kārgar; Afghans often use mosāfer, lit. “traveller”) who wants to send his savings to his family left behind in Afghanistan, the remittance specialist, and a middleman (dallāl), when the migrant worker and the remittance specialist do not know each other already; the middleman collects the migrant worker’s money and gives it to the remittance specialist, who is usually also a trader.

The middleman, as a type of broker, takes a commission which generally amounts to 1 percent (0.5 percent from the remittance specialist and 0.5 percent from the customer). Once he has collected the money of the migrant worker, the remittance specialist based in Iran, passes on a letter to a partner in Pakistan, stating the details of the transaction, and gives the equivalent of a credit note to the customer himself, to send it on to his family in Afghanistan (usually via a friend going back home).

In Pakistan, a merchant (tājer) associated with the remittance specialist (they are always close relatives) retrieves the money sent through the official banking system. He may invest the money in different commercial activities and may also work as a moneychanger (ṣarrāf), as this is a way to invest the money that they collect and thus diversify their sources of income.

This merchant in Pakistan purchases some goods (wheat, rice, cooking oil, sugar, tea, shoes, cloth, cooking pots, etc.) and dispatches them by truck to the family’s village in the Hazārajāt, where a third partner runs a shop. This shopkeeper (dokkān-dār) receives the goods, sells them, and uses the proceeds to reimburse the migrant’s family. In the meantime, they have been independently informed that they would receive this money from the shopkeeper, by the migrant worker’s associate on his arrival there from Iran.

These categories are ideal types. In practice, the middleman and the remittance specialist in Iran, the merchant in Pakistan and the shopkeeper in Afghanistan may even be the same person. If they are different individuals, they are invariably close relatives. However, if the migrant worker and the remittance specialist do not know each other, the mediation of a middleman becomes necessary.

As the amounts remitted increase, the more the functions tend to be differentiated. In such cases, the remittance specialist sometimes collaborates with an important trader (who may be Iranian) to transfer the money directly to a bank in Pakistan. Finally, it should be mentioned that the entire remittance system could not function without transport contractors and smugglers, most of whom tend to be Baluch, between Iran and Pakistan, and Pashtuns between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

There are three main sources of profit for the remittance specialist: (1) his commission; (2) exploiting advantages in the exchange rate between the different currencies (riāl, rupee, and afḡāni); (3) profits from the sale of the merchandise purchased with the money collected from the migrant. Usury is in theory prohibited for Muslims; interest on money, whether it is a loan or an investment, is illicit.

But commercial transactions do not exclude the payment of a fixed commission, which is considered as the fair recompense for services rendered. Usually, the commission does not exceed 5 percent, and ranges from 2 to 3 percent among the Hazāras between Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

The remittance specialist’s profit is earned mainly from the transaction itself and depends on factors, such as how distant the deadline for repayment is, and how close his relationship is with the migrant worker for whom he is providing this service.

Since most Hazāra remittance specialists do not keep any precise accounting records, and the different local currencies tend to get devalued very quickly, it is very difficult to determine the profit made in a single cycle of a ḥawāla credit transaction by the individual participants in the different locations. All of the commodities are much more expensive in the Hazārajāt than in Quetta.

The wide networks of transfer of funds set up by Hazā-ras and other Afghan refugees and migrants, which serve to facilitate sending their savings back to their families in Afghanistan, provide the basis for many economic and trading activities. All of the shops of the Hazārajāt operate according to this system, which provides them with all of their supplies. Its significance extends beyond its economic dimension.

Migration is not only a response to violence, war, and poverty, for it has also become a systematic strategy by means of which a community, such as the Hazāras, can widen their social and cultural horizons.

The transfer of funds is both a means of survival and a way to structure a transnational society. Indeed, it serves as a most efficient tool with which to reproduce social ties in the face of war and the dispersion of members of each domestic and solidarity group.

Despite the trauma of war and exile, the Hazāras have thus managed to take advantage of their geographic dispersion and the resulting economic diversification, by developing new transnational cooperation structures.

Facing a very difficult situation, Hazāra refugees and migrants, like other Afghans, have demonstrated their ability to adapt.

Using their existing cultural assets, while moving constantly between Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and beyond, they have been able to open new social, economic, and political perspectives.

The multiplicity of the registers of solidarity, which are not limited to lineage or tribal affiliation, the diversification of the basis of cooperation, the multidirectional migratory displacements, and the vast amount of money remitted to Afghanistan are some of the most striking features of the social strategies employed by the Hazāras in recent times.

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hazara-3

— — — — — — — — — — — —

Κατεβάστε το άρθρο του Said Reza Huseini,

Destruction of Bamiyan Buddha:

https://vk.com/doc429864789_618303058

https://www.docdroid.net/vT9KJru/said-reza-huseini-destruction-of-bamiyan-buddha-pdf

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — –

Επιπλέον:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afghanistan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhas_of_Bamyan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hazaras

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bamyan_Province

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Ali Yaser Shoayb — Salsal and Hazara 2013, Afghanistan

Ο πίνακας ζωγραφικής Σαλσάλ και Χαζάρα (Salsal and Hazara) του Αλί Γιάσερ Σουέιμπ (Ali Yaser Shoayb) δείχνει πόσο σημαντικό ρόλο τα πελώρια λαξευτά αγάλματα του Βούδα στο Μπαμιγιάν έπαιζαν στις παραδόσεις, τις δοξασίες και την παιδεία των Τουρκοφώνων Σιιτών Χαζάρα του Αφγανιστάν.

Πιο συγκεκριμένα, κατά τις παραδόσεις των Χαζάρα — που έφθασαν στην περιοχή πολλούς αιώνες μετά την λάξευση των αγαλμάτων στους εκεί βράχους — τα αγάλματα ανήκαν στο αστρικό ζεύγος ψυχικών οντοτήτων Σαλσάλ και Σαχμάμα των οποίων ο αποτυχημένος έρωτας επέφερε τον θάνατο.

Έτσι, οι δυο εραστές του ψυχικού κόσμου παρέμειναν για πάντα χωρισμένοι αφού μετατράπηκαν σε λίθο κι αποτυπώθηκαν πάνω στους εκεί βράχους για να κυττάζουν συνέχεια την γη και τον ουρανό.

Ο 23 ετών Χαζάρα Αφγανός καλλιτέχνης φιλοτέχνησε τον πίνακα αυτόν το 2013 στα 17 του χρόνια.

http://www.imagomundiart.com/artworks/ali-yaser-shoayb-salsal-and-hazara

----------------------------------

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε PDF ή Word doc.: https://www.academia.edu/59595218/Χαζάρα_οι_Καταπιεσμένοι_Τουρκόφωνοι_Σιίτες_του_Αφγανιστάν_αποτελούν_την_Ανατολική_Λαβίδα_του_Μυστικού_Κινήματος_των_Κιζιλμπάσηδων

https://vk.com/doc429864789_618303859

https://www.docdroid.net/ibHyR8N/xazara-oi-katapiesmenoi-toyrkofonoi-siites-toy-afghanistan-docx

No comments:

Post a Comment