Mehragan, the Parsis’ Great Autumn Feast in Iran & India: when Mazdeism’s Tradition comes through a Muslim, the Great Epic Poet Ferdowsi

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 1 Οκτωβρίου 2019.

Ευχαριστώντας με για την μετάφραση τμημάτων του επισυναπτόμενου βίντεο από τα φαρσί (περσικά), ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης αναπαράγει σημεία διαλέξεών μου για τους υπερβατικούς συμβολισμούς με τους οποίους ο Φερντοουσί παρουσιάζει στο έπος του την αρχή, την διάρκεια και το τέλος της Παγκόσμιας Ιστορίας, βλέποντας στους ήρωές του την διαχρονικότητα της Θείας Παρέμβασης και στους βασιλείς του τις αενάως αναπαραγόμενες και διαφοροποιούμενες κατ’ άτομο συνθέσεις των Μεγάλων Ιδεών.

— — — — — — — — — — — — —

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/10/01/μεχραγκάν-η-μεγάλη-φθινοπωρινή-εορτή/

======================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής — Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Αυτές τις μέρες, οι Παρσιστές του Ιράν και της Ινδίας γιορτάζουν μία από τις μεγαλύτερες εορτές τους, τα Μεχραγκάν. Όπως το ίδιο το όνομα δηλώνει, αυτή η εορτή είναι αφιερωμένη στον Μίθρα, ένα θεό του οποίου την υπόσταση προσπάθησε ο Ζωροάστρης χωρίς επιτυχία να εξαφανίσει και του οποίου (Μίθρα) τους πολυθεϊστικούς Μάγους οι Αχαιμενιδείς σάχηδες επίμονα προσπάθησαν να εξαφανίσουν.

Αυτό μάλιστα συνέβαλε στην δημιουργία μιας επιπλέον αρχαίας ελληνικής λέξης ως μετάφρασης από την αντίστοιχη αρχαία ιρανική: “Μαγοφονία”! Αυτό ειπώθηκε για την εξόντωση, από τον Δαρείο Α’ τον Μέγα, του Μάγου Γαυματά ο οποίος είχε αποπειραθεί να ανατρέψει την δυναστεία.

Ο Ηρόδοτος μάλιστα διασώζει ότι αυτή η περίσταση έγινε αμέσως ένας εορτασμός. Αυτό είναι ενδεικτικό των τρομερών συγκρούσεων ιερατείων που συνέβαιναν ακόμη και στην κορυφή της αχαιμενιδικής αυτοκρατορίας.

Ο Ζωροαστρισμός και ο Μιθραϊσμός ήταν δυο θρησκείες η μία στους αντίποδες της άλλης και ο τρόπος σύγκρουσης ιερατείων δεν είναι μόνον μάχες, πόλεμοι, στάσεις και δολοφονίες αλλά επίσης και αλλαγή του θρησκευτικού περιεχομένου μιας εορτής ή τροποποίηση των χαρακτηριστικών της. Σχετικά με τις ιρανικές θρησκείες από την Αρχαιότητα μέχρι σήμερα, μπορείτε να βρείτε μια σύντομη παρουσίαση εδώ:

Ιράν: η Χώρα που γέννησε Περισσότερες Θρησκείες από Οποιαδήποτε Άλλη, Πρώτη Χώρα που Θρησκείες της διαδόθηκαν από τον Ατλαντικό μέχρι τον Ειρηνικό

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/07/22/ιράν-η-χώρα-που-γέννησε-περισσότερες-θ/

(και πλέον: https://www.academia.edu/51404599/Ιράν_η_Χώρα_που_γέννησε_Περισσότερες_Θρησκείες_από_Οποιαδήποτε_Άλλη_Πρώτη_Χώρα_που_Θρησκείες_της_διαδόθηκαν_από_τον_Ατλαντικό_μέχρι_τον_Ειρηνικό)

Ιράν: η Χώρα που γέννησε τις Περισσότερες Θρησκείες, Πρώτη Χώρα που Θρησκείες της διαδόθηκαν από Ατλαντικό μέχρι Ειρηνικό — ΙΙ

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/08/21/ιράν-η-χώρα-που-γέννησε-τις-περισσότερ/

(και πλέον: https://www.academia.edu/51484958/Ιράν_η_Χώρα_που_γέννησε_τις_Περισσότερες_Θρησκείες_Πρώτη_Χώρα_που_Θρησκείες_της_διαδόθηκαν_από_Ατλαντικό_μέχρι_Ειρηνικό_ΙΙ)

Ο Μίθρας είναι ένας ιρανοϊνδικός θεός που διαδόθηκε ιδιαίτερα ανάμεσα στους Αραμαίους, τους Έλληνες, τους Ρωμαίους και όλους τους αρχαίους λαούς της Ευρώπης. Σε όλες τις μορφές και φάσεις ιρανικών γλωσσών ο Μίθρας έχει δύο ονόματα: Μιτρά και Μεχρ. Το δεύτερο είναι τμήμα του ονόματος της εορτής που εορτάζουν σήμερα οι Παρσιστές, χωρίς ωστόσο καμμιά επίκληση του Μίθρα. Ο Παρσισμός, ως τελευταίο στάδιο των αρχαίων ιρανικών θρησκειών, έχει διαμορφωθεί κάτω από την επίδραση δύο πολιτιστικών φαινομένων:

α. του Μαζδεϊσμού που είναι η σασανιδικών χρόνων (224–651 μ.Χ.) αναπροσαρμογή του Ζωροαστρισμού, και

β. της σύστασης του ιρανικού μυθικού επικού κύκλου κατά τα ισλαμικά χρόνια, όταν είτε Παρσιστές είτε Μουσουλμάνοι Ιρανοί προσπάθησαν να ανασυντάξουν την προϊσλαμική ιρανική πολιτισμική κληρονομιά και να την ανασυνθέσουν σε μια ενότητα παραδόσεων, κοσμολογίας, μυθικής αφήγησης του ιρανικού και του πανανθρώπινου παρελθόντος, σωτηριολογίας και εσχατολογίας.

Έτσι, προκλήθηκε ένα πολύ παράξενο και κυριολεκτικά μοναδικό φαινόμενο: η επίσημη θρησκεία του σασανιδικού Ιράν, ο μαζδεϊσμός, τερματίσθηκε. Όσοι Ιρανοί παρέμειναν προσηλωμένοι σ’ αυτήν την θρησκεία, την διατήρησαν στις κοινότητές τους, πλην όμως όχι ως επίσημη αυτοκρατορική θρησκεία, εφόσον άλλωστε ανήκαν στο ισλαμικό χαλιφάτο. Έτσι, διαμορφώθηκε ο Παρσισμός, ένα μετα-μαζδεϊστικό στάδιο ιρανικής θρησκείας της οποίας οι πιστοί σήμερα ανέρχονται σε μερικές εκατοντάδες χιλιάδες ανθρώπων στο Ιράν και στην Ινδία.

Από την άλλη, όσοι Ιρανοί προσχώρησαν στο Ιράν, συνέθεσαν ένα ιρανοϊσλαμικό κύκλο επών και μυθικής αφήγησης της Ιστορίας μέσα στον οποίο το προϊσλαμικό παρελθόν του Ιράν παρουσιάσθηκε ως ισλαμικού χαρακτήρα και αποδεκτό για το Ισλάμ. Όμως αυτός ο κύκλος επών έγινε εξίσου δεκτός από τους Ιρανούς που δεν έγιναν Μουσουλμάνοι και, διατηρώντας ό,τι είχαν μπορέσει από την παλιότερη, αυτοκρατορική θρησκεία τους, διαμόρφωσαν τον Παρσισμό.

Έτσι, σήμερα στο Ιράν, όταν συναντήσουμε κάποιον που ονομάζεται Φερεϋντούν (το οποίο είναι ντε φάκτο ένα προϊσλαμικό ιρανικό προσωπικό όνομα), δεν μπορούμε σε καμμιά περίπτωση να ξέρουμε, αν αυτός είναι Μουσουλμάνος ή Παρσιστής. Και εννοείται ότι είναι μακρύς ο κατάλογος των ονομάτων αυτών που, όντας προϊσλαμικά ιρανικά, έχουν γίνει ολότελα αποδεκτά από τους μουσουλμάνους Ιρανούς και επιλέγονται ως δικά τους προσωπικά ονόματα.

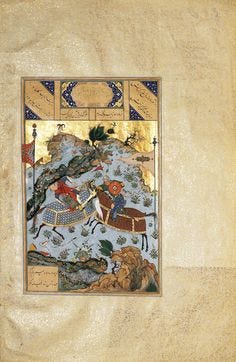

Η νίκη του Φερεϋντούν επί του Ζαχάκ, κεντρικό θέμα της παρσιστικής εορτής των Μεχραγκάν, εδώ απεικονίζεται σε σμικρογραφία χειρογράφου του έπους Σαχναμέ του Φερντοουσί, μουσουλμάνου εθνικού ποιητή των Ιρανών και των Τουρανών.

Καθώς μάλιστα οι Ιρανοί και οι Τουρανοί αποτελούν ένα αδιαχώριστο σύνολο εθνών, όλη αυτή η ιρανική πολιτισμική κληρονομιά και επική παράδοση έχει επίσης διαδοθεί ανάμεσα σε όλα τα τουρανικά και μογγολικά φύλα.

Ονόματα όπως Ρουστάμ, Φερεϋντούν, Κέυ Κουμπάντ, Κέυ Καούς, Κεϋχοσρόης, Εσκαντέρ, Σιγιαβούς, Αφρασιάμπ, κλπ είναι προσωπικά ονόματα κατοίκων της Τουρκίας, της Συρίας, του Ιράκ, του Αζερμπαϊτζάν, του Αφγανιστάν, του Πακιστάν, της Ινδίας, της Κίνας, της Ρωσσίας, και όλων των χωρών της Κεντρικής Ασίας — στον μεγαλύτερο βαθμό τους προσωπικά ονόματα Μουσουλμάνων και σε μικρότερο βαθμό προσωπικά ονόματα Παρσιστών.

Ο βασικός χαρακτήρας των Μεχραγκάν (جشن مهرگان , جشن ملی ایرانیان / εορτασμός Μεχραγκάν — εθνικός εορτασμός των Ιρανών / τζεσν Μεχραγκάν — τζεσν μελί-γιε Ιρανιάν) είναι ο εορτασμός της φθινοπωρινής ισημερίας.

Έτσι, αυτόματα, η εορτή αυτή είναι η δεύτερη σημαντικώτερη των Παρσιστών μετά το Νοουρούζ, το οποίο εορτάζεται κατά την εαρινή ισημερία και αποτελεί την ιρανική Πρωτοχρονιά είτε για τους Μουσουλμάνους είτε για τους Παρσιστές.

Λόγω της ύπαρξης αρκετών ιστορικών ιρανικών ημερολογίων και της αναπροσαρμογής κάποιων από αυτά, συχνά οι ημερομηνίες του εορτασμού διαφέρουν.

Οι επικρατέστερες ημερομηνίες είναι οι πρώτες ημέρες του Οκτωβρίου.

Δεν σώζονται αναφορές σε Μεχραγκάν στα αχαιμενιδικά χρόνια, και προφανώς η εορτή ως μιθραϊστική και αντίθετη στα κηρύγματα του Ζωροάστρη θα είχε απαγορευθεί.

Αλλά για τους Μιθραϊστές ήταν μια πολύ σημαντική εορτή.

Η πρώτη αναφορά σε Μεχραγκάν ανάγεται στα σασανιδικά χρόνια, δηλαδή λίγο καιρό πριν τον εξισλαμισμό του Ιράν.

Η επικράτηση του Μιθραϊσμού στα αρσακιδικά χρόνια (250 π.Χ. — 224 μ.Χ.) είχε υποχρεώσει τους Σασανιδείς που ανήλθαν στην εξουσία το 224 μ.Χ. να κάνουν κάποιους συμβιβασμούς.

Όμως, η ηρωοποιητική προβολή του Ιράν ως εκλεκτού λαού του Άχουρα Μαζντά κατά τα σασανιδικά χρόνια από τον Καρτίρ έδωσε τον ουσιαστικό χαρακτήρα του Μαζδεϊσμού, της τότε αυτοκρατορικής θρησκείας που επιχείρησε να κάνει τους Ιρανούς ένα έθνος ηρώων και τους Σάχηδες αυτοκράτορες όλης της γης.

Ο Ζαχάκ σκοτώνει τον ταύρο.

Έτσι, η παλιά εορτή των Μιθραϊστών διατηρήθηκε στα σασανιδικά χρόνια πλην όμως πήρε ένα χαρακτήρα πανηγυρισμού της νίκης του μυθικού ήρωα Φερεϋντούν επί του Ζαχάκ, του αρνητικού και κακοβουλου ηγεμόνα. Το βασικώτερο χαρακτηριστικό του Ζαχάκ ήταν το κυνήγι ταύρου και η ταυροκτονία. Όμως, εντελώς συμπτωματικά, το βασικώτερο χαρακτηριστικό του Μίθρα ήταν η ταυροκτονία.

Η σύγκρουση του Φερεϋντούν με τον Ζαχάκ

Έτσι, καταλαβαίνουμε ότι οι Μαζδεϊστές διατήρησαν την μιθραϊστική εορτή, δίνοντας όμως εντελώς αρνητικό χαρακτήρα στο μέγιστο επίτευγμα του Μίθρα. Πουθενά αλλού δεν περιγράφεται η σύγκρουση Φερεϋντούν και Ζαχάκ καλύτερα από το Σαχναμέ του Φερντοουσί, του εθνικού ποιητή του Ιράν, ο οποίος αν και μουσουλμάνος είναι αυτός που χρωμάτισε περισσότερο τον εορτασμό των συγχρόνων Παρσιστών.

Έτσι, κι αυτοί εορτάζουν μια εορτή της οποίας το όνομα παραπέμπει στον Μίθρα και το περιεχόμενο αφορά απόρριψη του έργου του Μίθρα.

Η μάχη του Φερεϋντούν με τον Ζαχάκ

Στην συνέχεια, μπορείτε να δείτε ένα βίντεο που παρουσιάζει όψεις του εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν από τους σύγχρονους Παρσιστές. Στο εισαγωγικό σημείωμα θα βρείτε επεξηγήσεις (σε ελληνικά, αγγλικά και ρωσσικά) για το κάθε τι που δείχνει το βίντεο λεπτό προς λεπτό.

Ευχαριστώ ιδιαίτερα τον διακεκριμμένο ιρανολόγο και ανατολιστή, καθ. Μουχάμαντ Σαμσαντίν Μεγαλομμάτη για την μετάφραση σε νέα ελληνικά των βασικών σημείων του βίντεο, το οποίο είναι ηχογραφημένο σε φαρσί (νέα περσικά). Στην συνέχεια, θα βρείτε πληροφοριακά κείμενα σχετικά με τα Μεχραγκάν.

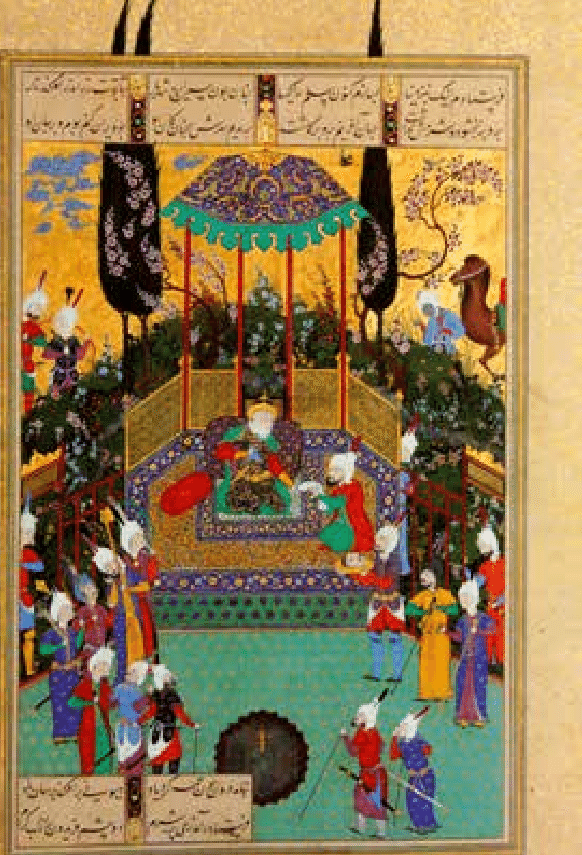

Ο Φερεϋντούν υποδέχεται τον Τουρσάντ

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Мехраган, Великий осенний праздник парсов в Иране и Индии (مهرگان)

https://www.ok.ru/video/1522499062381

Περισσότερα:

01:43–01:57 Великий иранский эпический герой Ферейдун

02:00–03:00 Праздничные аспекты современных торжеств Мехреган

03:00–03:30 Осеннее Равноденствие — Меграган (эквивалентно празднику Навруз, который совпадает с Весенним Равноденствием, поэтому является Новым годом для мусульманских иранцев и парсов)

03:30–03:45 Поэзия Насира Хусрава, иранского шиитского поэта-исмаилита, философа и математика

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasir_Khusraw

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Насир_Хосров

03:46–04:10 Персеполис (известный иранцам как Тахт-э Джамшид: трон Джамшида, главного героя иранского эпоса, описанного в «Шахнаме» Фердоуси и многих других иранских эпосах)

04:10–04:47 Праздничные аспекты современных торжеств Мехреган

04:48 Статуя Фердоуси («Райский»), национальный иранский поэт (10 в)

04:50–05:50 Выживание праздников Мехреган после завоевания Ирана мусульманами, турками и монголами

6:00–06:50 Барельеф Митры в Так-Бостане — Иран; представления Митры в индийском, иранском и среднеазиатском искусстве

06:50–07:00 У современных парсов образы Ахура Мазды и Зороастра обычно идентичны.

07:05–07:15 Ссылки на Ахура Мазду в клинописных древнеахеменидских иранских текстах

07:20–07:40 Отрывки из Хорде Авесты (Маленькая Авеста)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khordeh_Avesta

07:40 Праздничные аспекты современных торжеств Мехреган

08:15 Доисламские иранские концепции и верования сохраняются в религиозном, шиитском и суннитском, исламском танце семах

08:42 Персеполис / Тахт-Джамшид

09:00 Дариус I Барельеф в Бехистуне / Бисотуне возле Экбатаны (Хамедан)

09:11 Немруд Даг, юго-восточная Турция: греко-иранское пиковое святилище, самое святое место королевства Коммагены

9:30 Различные памятники иранской цивилизации

09:55 Ссылка на иранского мифического героя Ферейдуна и его победу над Заххаком, который считается отправной точкой праздника Мехреган

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fereydun

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Траэтаона

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zahhak

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Заххак

10:30 Праздничные аспекты современных торжеств Мехреган

10:52 Аль Бируни (ведущий мусульманский историк, математик и астроном: XI-XI века) — ссылки на Мехреган

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Biruni

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Аль-Бируни

11:15 Снимки с торжеств Мехреган; ряд иранских памятников и древностей; и изображения сцен из иранских эпосов, в частности, битвы между Ферейдуном и Заххаком

12:50 Слово «Мехреган» было распространено среди арабов уже в доисламские времена, что означает «празднование» или «праздничная годовщина».

13:10 Параллели с древнегреческими религиозными праздниками

13:20 Значительные Мехреган отмечены в истории

14:00 Праздничные аспекты современных торжеств Мехреган

Больше:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehregan

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Мехреган

Απεικόνιση του Φερεϋντούν στην νεώτερη ιρανική τέχνη

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Mehragan (Мехреган), the Great Autumn Celebration of the Parsis in Iran and India (مهرگان)

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240311

Περισσότερα:

01:43–01:57 Representations of Fereydun

02:00–03:00 Festive aspects of modern celebrations of Mehragan

03:00–03:30 Autumn Equinox — Mehragan (equivalent to the feast of Nowruz, which coincides with the Spring Equinox, being therefore the New Year’s Day for Muslim Iranians and Parsis)

03:30–03:45 Poetry by Nasir Khusraw, Iranian Shiite Ismaili poet, philosopher and mathematician

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasir_Khusraw

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Насир_Хосров

03:46–04:10 Persepolis (known to Iranians as Takht-e Jamshid: the throne of Jamshid, the foremost hero of the Iranian epic described in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and many other Iranian epics)

04:10–04:47 Festive aspects of modern celebrations of Mehragan

04:48 Statue of Ferdowsi (‘the Paradisiacal’), the national Iranian poet (10th c)

04:50–05:50 Survival of Mehragan celebrations after Iran’s conquest by Muslims, Turks and Mongols

6:00–06:50 Bas-relief of Mithra in Taq-e Bostan — Iran; representations of Mithra in Indian, Iranian and Central Asiatic art

06:50–07:00 Among modern Parsis, the representations of Ahura Mazda and Zoroaster are usually identical.

07:05–07:15 References to Ahura Mazda’s in cuneiform Old-Achaemenid Iranian texts

07:20–07:40 Excerpts from Khordeh Avesta (Little Avesta)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khordeh_Avesta

07:40 Festive aspects of modern celebrations of Mehragan

08:15 Pre-Islamic Iranian concepts and beliefs are preserved in the religious, Shiite and Sunni, Islamic dance Semah

08:42 Persepolis / Takht-e Jamshid

09:00 Darius I ‘s relief in Behistun / Bisotun near Ekbatana (Hamedan)

09:11 Nemrud Dagh, south-eastern Turkey: the Greek-Iranian peak sanctuary, the holiest place of the kingdom of Commagene

9:30 Various monuments of the Iranian civilization

09:55 Reference to the Iranian mythical hero Fereydun and his victory over Zahhak which is thought to have been the starting point of the Mehragan feast

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fereydun

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Траэтаона

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zahhak

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Заххак

10:30 Festive aspects of modern celebrations of Mehragan

10:52 Al Biruni (leading Muslim historian, mathematician and astronomer: 10th-11th century) — references to Mehragan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Biruni

11:15 Snapshots from Mehragan celebrations; a number of Iranian monuments and antiquities; and representations of scenes from the Iranian epics, notably the battle between Fereydun and Zahhak

12:50 The word ‘Mehragan’ was diffused among Arabs already in Pre-Islamic times, meaning ‘celebration’ or ‘festive anniversary’

13:10 Parallels with ancient Greek religious festivals

13:20 Significant Mehragan celebrations recorded in History

14:00 Festive aspects of modern celebrations of Mehragan

More:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehregan

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Мехреган

Ζαχάκ: ο κακόβουλος ηγεμόνας

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Μεχραγκάν, η Μεγάλη Φθινοπωρινή Εορτή των Παρσιστών (Mehregan / مهرگان)

Περισσότερα:

Αυτές τις μέρες, οι Παρσιστές του Ιράν και της Ινδίας γιορτάζουν μία από τις μεγαλύτερες εορτές τους, τα Μεχραγκάν.

(جشن مهرگان , جشن ملی ایرانیان)

(εορτασμός Μεχραγκάν — εθνικός εορτασμός των Ιρανών / τζεσν Μεχραγκάν — τζεσν μελί-γιε Ιρανιάν)

01:43–01:57 Αναπαραστάσεις του Φερεϊντούν

02:00–03:00 Όψεις σύγχρονου εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν

03:00–03:30 Φθινοπωρινή ισημερία — Μεχραγκάν (αντίστοιχο της εαρινής ισημερίας που είναι η ιρανική, μουσουλμανική και πασριστική, Πρωτοχρονιά — Νόουρουζ)

03:30–03:45 Στίχοι του Νάσερ Χουσράου, Ιρανού Σιίτη Εβδομοϊμαστή ποιητή, φιλοσόφου και μαθηματικού του 11ου αι

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasir_Khusraw

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Насир_Хосров

03:46–04:10 Περσέπολη (γνωστή στους Ιρανούς ως Ταχτ-ε Τζαμσίντ: Θρόνος του Τζαμσίντ, κορυφαίου ήρωα του ιρανικού έπους που έχει περιγραφεί στο Σαχναμέ του Φερντοουσί και σε πλήθος άλλων ιρανικών επών)

04:10–04:47 Όψεις σύγχρονου εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν

04:48 Άγαλμα του Φερντοουσί (: Παραδεισένιου) εθνικού ποιητή του Ιράν (10ος αι)

04:50–05:50 Επιβίωση του εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν μετά τις κατακτήσεις του Ιράν από τους Μουσουλμάνους, τους Τούρκους και τους Μογγόλους

6:00–06:50 Ανάγλυφο του Μίθρα στο Ταγ-ε Μποστάν — Ιράν και απεικονίσεις του Μίθρα στην ινδική, ιρανική και κεντρασιατική τέχνη

06:50–07:00 Στους νεώτερους Παρσιστές οι απεικονίσεις του Άχουρα Μαζντά και του Ζωροάστρη συγχέονται και ταυτίζονται.

07:05–07:15 Αναφορές του Άχουρα Μαζντά σε σφηνοειδή αρχαία αχαιμενιδικά ιρανικά κείμενα

07:20–07:40 Απαγγελία από την Χορντέ Αβέστα (μικρή Αβέστα)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khordeh_Avesta

07:40 Όψεις σύγχρονου εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν

08:15 Διατήρηση ιρανικών προϊσλαμικών παραδόσεων στον ισλαμικό σιιτικό και σουνιτικό θρησκευτικό χορό Σαμά

08:42 Περσέπολη / Ταχτ-ε Τζαμσίντ

09:00 Ανάγλυφο του Δαρείου Α’ στο Μπεχιστούν / Μπισοτούν κοντά στα Εκβάτανα

09:11 Νέμρουντ Νταγ, νοτιοανατολική Τουρκία: ελληνοϊρανικό ιεροθέσιο κορυφής της Κομμαγηνής

9:30 Διάφορα μνημεία ιρανικού πολιτισμού

09:55 Αναφορά στον ιρανικό μυθικό ήρωα Φερεϊντούν και την νίκη του επί του Ζαχάκ που υστερογενώς εκλήφθηκε ως αρχή του εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν

10:30 Όψεις σύγχρονου εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν

10:52 Αλ Μπιρούνι (κορυφαίος μουσουλμάνος ιστορικός, μαθηματικός κι αστρονόμος: 10ος- 11ος αι.) — αναφορές σε Μεχραγκάν

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Biruni

11:15 Σκηνές από εορτασμούς των Μεχραγκάν, ποικίλα ιρανικά μνημεία και αρχαιότητες, και αναπαραστάσεις σκηνών από την ιρανική εποποιΐα, ιδιαίτερα της μάχης μεταξύ Φερεϊντούν και Ζαχάκ

12:50 Διάδοση της λέξης ‘Μεχραγκάν’ στα αραβικά με την γενική έννοια ‘εορτασμός’, ‘εορταστική επέτειος’

13:10 Παράλληλα με αρχαιοελληνικές εορτές

13:20 Σημαντικοί εορτασμοί Μεχραγκάν στην Ιστορία

14:00 Όψεις σύγχρονου εορτασμού των Μεχραγκάν

Επιπλέον:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehregan

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Мехреган

— — — — — — — — — — — — —

Διαβάστε:

The Festival of Mehregan

Mehregan is one of the most ancient Iranian festivals known, dating back at least as far as the proto- Iranians. According to Dr. Taqizadeh, (1938, p. 38: “The feast of Mithra or baga was no doubt one of the most popular, if not the greatest of all the festivals for the ancient Iranians, where it was celebrated with the greatest attention.

This was originally an old-Iranian and pre-Zoroastrian feast consecrated to the sun-god and its’ place in the Old-Persian calendar was surely in the month belonging to this deity.

This month was called Bagayadi or Bagayadish and almost certainly corresponded to the seventh Babylonian month Tishritu, the patron of which, was also Shamash, the Babylonian sun god.

This month was, as has already been stated, probably the first month of the Old-Persian year, and its more or less fixed place was in the early part of the autumn.

The feast was in all probability pre-Zoroastrian and it was perhaps the survival of an earlier Iranian New Year festival dating from some prehistoric phase of the Proto-Iranian (Aryan) calendar, when the year began at the autumnal equinox. It was connected with the worship of one of the oldest Iranian deities (Baga-Mithra), of whom traces are found as far back as in the fourteenth century BCE.

In the Zoroastrian religious calendar, Mehregan is celebrated on the sixteenth day of the seventh month. According to Fasli reckoning, this occurs on October 1st. Modi (1922), p. 463, states that Mehregan should properly fall on the fall equinox (which is the first day of the seventh month), but it is usually performed on the name day of Mithra (16th day). Meherjirana (1869, tr 1982 by Kotwal and Boyd) p. 161 says that this feast is important for the following reasons:

“This jashn is called Mehregan and is a time for love and gratitude for life. [In ancient times] Zohak was very cruel to the people. So a blacksmith named Kaveh, with the help of others, sought out Faridoun who then caught Zohak and prisoned him in mount Damavand. Faridoun then became king and the peoples’ lives were saved. For these reasons, King Faridoun and all the people had a great jashan on that day. It is so stated in the Persian Vajarkard Dini.”

According to Zoroastrian angelology, Mithra is the greatest of the Yazats (angels), and is an angel of light, associated with the sun (but distinct from it), and of the legal contract (Mithra is also a common noun in the Avesta meaning contract). He has a thousand ears, ten-thousand eyes.

The feast of Mehregan is a community celebration (Jashan), and prayers of thanksgiving and blessings of the community (Afarinagan) figure prominently in the observances.

In the Rig Veda, Mitra figures prominently mentioned over 200 times.

The Sun is said to be the eye of Mitra, or of the compound Asura “Mitravaruna” (analogous to Mithra-Ahura in Avesta), who wield dominion by means of maya (occult power).

They are guardians of the whole world, upholders of order, barriers against falsehood. (The Vedic language also has a common noun Mitra meaning ‘friend’.)

In the angelology of Jewish mysticism, as the result of Zoroastrian influence, Mithra appears as Metatron, the highest of the angels.

He also appeared as Mithras, god of the Mithraic religion popular among the Roman military.

He can also be found in Manichaeism and in Buddhist Soghdian texts. Mehregan, Tiragan, and Norooz, were the only Zoroastrian feasts be mentioned in the Talmud, which is an indication of their popularity.

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Celebrations/mehregan.htm

— — — — — — — — — — —

Mehregān

Mehregān (Mehrgān/Mehregān; Ar. Mehrajān; Meherangān among the Parsis), an Iranian festival apparently dedicated to the god Miθra/Mehr, occurring also in onomastics and toponymy.

By extension this name is used with the generical meaning of autumn and identifies a musical mode. In the Mazdean annual schema of feasts, the festival occurs on the day Mehr of the month Mehr, that is, the 16th day of the 7th month. In some almanacs the occurrence of Mehragān is marked at the 10th of Mehr, after the modern reform (1925 CE) of the Iranian calendar (Ruḥ-al-Amini, p. 83).

Αναπαράσταση — των αχαιμενιδικών χρόνων — του Μίθρα επί λέοντος υπό εμφανή ασσυριακή τεχνοτροπική επίδραση

The name of the festival is to be found in the Jerusalem Talmud and in that of Babylon (Taqizāda, pp. 192, 214; tr. pp. 158–59, 311; Bokser, pp. 261–62; Neusner, pp. 185–86).

According to Masʿudi (Moruj, sec. 1287), in the Christian milieu of Syria and Iraq, the word Mehrajān indicated the first day of winter.

The Arabic form Mehrajān identifies also a festival widespread outside the Iranian plateau. In a variant of the Aḥsan al-taqāsim by Moqaddasi (p. 45, n. d), there is mention of its celebrations in ʿAden, where the author has been visiting around the end of the 9th century (Cristoforetti, pp. 162–63).

On the basis of some Arabic verses of the Sicilian poet ʿAli b. ʿAbd-al-Raḥmān Ballanubi, Mehrajān celebrations were observed in Cairo in the 11th-12th centuries (Corrao, p. 56).

After its prohibition, at an unknown date, this “Coptic” festival was allowed again by the Fatimid caliph al-Ẓāher (r. 1021–36; Corrao, p. xxxvii). For Egypt one can envisage a symmetry between Mehrajān and the local festival Nayriz, which clearly derives from Nowruz and occurs at the 1st of the Coptic month of Tut (September 10–11). We know that in modern times a Mehrajān festival occurs in mid-February in Somalia (Cerulli, p. 162). According to Ebn ʿEḏāri (p. 84), in 399/1009 in Andalus Mehrajān occurred at the end of Šawwāl, which corresponds to the last ten days of June.

In Andalus during 10th century, the name ʿAnsara was much more in use than the Persian derived name Mehrajān for the same festival (Lévi-Provénçal, p. 172 n. 1). The coincidence with the St. John festival and its fires (24th of June) makes one think of a symmetrical Andalusi Nayriz festival on the 1st of January, but the general lack of information on the matter does not allow one to say anything conclusive (for Arabic sources about Christian festivals in Andalus, including Mehrajān, see Fernando de la Granja). The relation of symmetry and consequent analogy between Mehrgān and Nowruz is frequently asserted in the extant sources (see below). This is the basis on which one may make inferences about the ancient rites of Mehrgān.

The name of the festival Mehragān is formed of the proper noun Mehr (Old Pers. Miθra/Mithra, a diety) and the suffix –agān, which is used in many names of the Mazdean festivals (on this point and for a survey of other possible etymologies, see Calmard, p. 15). Walter Belardi (esp. pp. 61–149) has done a detailed study on the position of Mithra/Mehr in the Iranian calendar. His study is focused on the significant meaning of the name of this Indo-Iranian god, based on the common noun *mitrá, as “pact, contract, covenant,” and on Mithra/Mehr’s function as an arbiter (cf. Boyce, 1975–82, I, pp. 24–31). This function is well testified by his Greek attribute mesítēs (according to Plutarch, De Iside et Osiride, 46) and by the Iranian and para-Iranian sources, in which Mithra/Mehr acts as arbitrator on the cosmological, eschatological, and anthropological levels (Belardi, pp. 32–45).

The Mehragān festival is clearly correlated to the equinox (see Biruni, Āṯār, p. 222; tr., p. 208), which is the astronomical phenomenon most easily linked to the concept of equity and equilibrium. But it remains uncertain whether the festival was in honor of Mithra or if the dedication to Mithra was, in Ḥasan Taqizāda’s view, serendipitous. According to Taqizāda (pp. 350–51; tr., p. 145), the reason may as well be a compromise that occurred in the process of adoption of some ancient religious beliefs by Zoroastrians.

Hence, the celebration of Baga Mithra in the 7th month of the Achaemenian calendar Bagayadi- (Av. Bāgayāday-) may have been added to the “new-Avestan” calendar in a period (second half of the 5th century BCE) in which the seasonal celebrations for the autunm equinox coincided with the 16th of Mehr. The name of the festival (*bāgayāda?) had been replaced by the name that this festival features in the “new-Avestan” calendar, that is Mehragān (<*miθrakāna).

Taqizāda’s hypothesis implies that the name of the Achaemenian month was taken to mean “(the month of) the worship of Baga,” assimilated with Mithra, but this interpretation has been rejected for philological reasons (Boyce, 1981, pp. 66–68; idem, 1982, II, pp. 16–18, esp. p. 24; on the name Baga, see Gignoux, pp. 88–90).

In fact, the only possible analogy between the Achaemenian celebration and the posterior Mehragān could be found in the stated celebration for the triumph of justice over usurpation, respectively represented by the victory of Darius I the Great over Gaumāta and of the epic hero Ferēdūn over Bēvarasp (Żaḥḥāk).

According to Taqizāda (p. 350; tr., p. 145), the Iranian epic preserved the memory of the coincidence of Mehragān with the day on which the usurper Gaumāta was killed by Darius I in 522 BCE. Some of the rites used on Magophonia, that is, the commemoration of the murder of the magi, or “of the magus” Gaumāta under Darius I, may have influenced the observance of *Mithrakāna (see Boyce, 1975–82, II, pp. 86–89; Hartner, p. 749; Henning, pp. 133–44; Dandamaev, pp. 138–40; Widengren, pp. 163–66).

It is noteworthy that the report by Ebn al-Balḵi (pp. 90–91) about the massacre of the Mazdakites ordered by Ḵosrow I Anuširavān (r. 531–79 CE) on the occasion of the great banquet for Mehragān could confirm the analogy, but this passage would also imply that Mehragān was an official occasion in which the king assigned “duties and assignments” (kārhā wa šoḡlhā; cf. Ps.-Jāḥeẓ, Ketāb al-tāj, p. 144; tr., p. 164; cf., for Nowruz, ḴELʿAT).

The festival, which was once connected to the solar calendar of the Iranian tradition, evidently suffered all the consequences of the complex evolution of the various forms of that calendar used by the Iranian people. Originally, and probably until the early Sasanian period, Mehragān was a single day (Boyce, 1970, pp. 518–19; idem, 1982, II, p. 34), but it seems to have been duplicated during the Islamic age as a Small or General Mehragān and a Great or Special Mehragān, as is the case of Nowruz and other festivals (Biruni, Āṯār, pp. 223–24; tr., p. 209).

This kind of duplication, producing a distance of five days between these two festivals, is clearly related to the general issue of interventions in the Iranian calendar, on which scholarly opinions differ notably (Bickerman, p. 203; Boyce, 1970, pp. 514–29; Balinski, p. 99; Marshak, pp. 145–52; de Blois, pp. 40–41, 46–49; Scarcia, pp. 133–41). The Arabic sources (e.g., Biruni, Āṯār, pp. 222–23; tr., pp. 207–9; Ṯaʾālebi, pp. 33–35) testify to attempts, clearly a posteriori, to explain those duplications on the basis of two different moments in the epic tradition being referred to; concerning Mehragān, they attribute it to the rebellion of Kāva and the triumph of Fereydun over Bēvarasp.

The fact that the epic tradition plays a role also in connection with the Sada festival may be due to the occurrence of the calendrical Mehragān in the traditional seasonal place of the Sada festival during the 6th and 7th centuries CE (Cristoforetti, 2002, p. 295). According to Biruni, the Sasanian king Ohrmazd I (r. 272–73 CE) joined the Small and the Great Mehragān, thereby turning it into a six-day festival (according to Taqizāda, pp. 351 n. 496, tr. p. 323 n. 496, this enlargement is a phenomenon that had already occurred in a more ancient time).

The fact that festivals were extended is supported for the later Sasanian times by a Byzantine document dated 565 CE (Boyce, 1983, pp. 807–8). However, afterwards the kings and the people of Iran celebrated the festival over thirty days, “distributing them over the several classes of the population in the same way as we have heretofore explained regarding Nowruz” (Biruni, Āṯār, p. 224; tr., p. 209; cf. idem, Tafhim, pp. 254–55). Biruni’s note that Nowruz was celebrated for thirty days through the month of Farvardin, if taken at face value, would make it reasonable to assume that the festival of Mehragān also lasted for the same number of days, starting on the day of Mehragān and ending on the 15th of Ābān.

It is possible to see a relation between this ambiguous passage by Biruni and the fact that Ferdowsi (I, p. 89, v. 3) talks about a Mehrgān of the 1st of Mehr as in perfect symmetry to the Nowruz of the 1st of Farvardin (cf. Modi, 1922, p. 463). The following sentence attributed to Salmān Fārsi (Biruni, Āṯār, p. 222; tr., p. 208) clearly reflects such symmetry between the two festivals in a different way: “In Persian times we used to say that God has created an ornament for his slaves, of rubies on Nowruz, of emeralds on Mehrajān.

Therefore these two days excel all other days in the same way as these two jewels excel all other jewels” (cf. similar point in Ps-Jāḥeẓ, Maḥāsen, p. 361).

This close relation of perfect twinship is also reflected by the fact that in Arsacid times “Nō Rōz came to be celebrated at the autumn equinox, and Mihragān at the spring one, the two poles of the religious year thus changing places” (Boyce, 1983, p. 805; cf. idem, 1979, p. 106).

According to Mary Boyce, the original festival may have been renamed under the influence of a Babylonian autumn festival, which was “under the protection of Shamash, Mithra’s Mesopotamian counterpart” (Boyce, 1982, II, p. 35).

However, all of our information concerning the Mehragān festival is provided by sources of non-Iranian origin (Rajabi, p. 222).

In Greek authors we find only mentions of generic celebrations: “The dominant aspect is that of a royal festival of a new year or renewal, celebrated by festivities, present-giving, animal sacrifices” (Calmard, p. 16).

According to Ctesias, it was the only annual occasion on which it was proper for the king of Persia to get inebriated (cf. Boyce, 1975, I, p. 173, who connects the practice with the use of soma/haoma).

Nevertheless, another dominant feature of the festival seems to have been its royal and solar aspect; on the day of Mehragān, the day of the creation of the sun itself, the king would wear a crown engraved with the image of the sun (Biruni, Āṯār, p. 222; tr., p. 207).

As regards the Arsacids, a passage in Ṯaʿālebi (p. 47) referring to an official meeting between Ḵosrow son of Firuz (Osroes II? r. ca. 190–95 CE) and the chief of the Zoroastrian priests seems to be the most ancient testimony of customs regarding exchanging of gifts on Mehragān.

But both the name of the ruler and the congruity of the two characters recall the well-known topos of wisdom of Ḵosrow I Anuširavān and his most wise minister Bozorgmehr.

According to Boyce (1983, p. 808), the major festivals, including Mehragān, “continued to be six-day festivals till some time after the 10th century A.D. (when they too were reduced to five, the sixth day of each being then abandoned).”

During the islamization of Iran, we find different attitudes towards traditional Iranian festivals, not only with differences between Muslims and Zoroastrians, but also between the Parsis of India and the Zoroastrians of Iran, who even used different forms of the Iranian calendar (Boyce, 1968, p. 213, n. 86; idem, 1977, pp. 164–67; idem, 1979, p. 221).

Probably under pressure from their Hindu surroundings, opposing to animal sacrifice which the Parsis of India were still practicing in the 18th century (witnessed by Anquetil-Duperron; cf. Boyce, 1966, p. 107; idem, 1975, p. 106), the festival declined among them during the 19th century, and the celebration is now limited to the 16th of the month of Mehr (Boyce, 1969, p. 32; Dhabhar, p. 343, on the ritual; Modi, 1889; idem, 1922, p. 460). The Iranian Zoroastrians, among whom an important sanctuary was dedicated to Mehr Izad in Kerman, continue to celebrate it by animal sacrifices, including the meat of a typical solar animal symbol such as the cock (Boyce, 1975, pp. 108–9, 117–18; idem, 1977, pp. 54–55, 83–87; Ruḥ-al-Amini, p. 84).

Muslim sovereigns and other rulers celebrated Mehragān as a purely secular festival.

The term “gifts of Nowruz and Mehrajān” attested since the early Islamic period should mean a kind of tax apart from those under Sharia law, and it was in fact abolished several times (Qomi, pp. 411–12; Ps.-Jāḥeẓ, Ketāb al-tāj, pp. 146–47; tr., pp. 165–66; cf. Lambton, 1948, pp. 595–96; Rajabi, p. 228).

However, no specific study has yet been done on the fiscal aspect of these gifts (see Lambton, 1994, pp. 145–47).

Mehragān is mentioned in a poem by Maḥmud b. Ḥosayn Košājem, an Arab poet of the 4th/10th century (Sharlet, pp. 266–67), one of many general references made in poetry during the ʿAbbasid Caliphate, which was established in the former Sasanian territory in southern Iraq, where socio-cultural life was well influenced by Iranian tradition.

The great enjoyment of the festival, with its clamor, lights, banquets, music, and games is celebrated in both Arabic (see for example Ps.-Jāḥeẓ, Maḥāsen, p. 374) and Persian poetry (see Dehḵodā, Loḡat-nāma, s.v.; Calmard, p. 18).

Masʿudi mentions a poetic fragment attributed to the caliph al-Maʾmun (r. 813–17), in which Mehragān is called a royal festival (ʿid ḵosravāni), the occasion when he would drink wine.

Masʿudi also mentions a report to the caliph al-Rāżi (r. 934–40) of an elaborate celebration of Mehragān on the Tigris at the home of the Turk general Bajkam, the like of which in excitement, amusements, play, pleasure, and merriments had not been seen (Masʿudi, Moruj, secs. 3502–503).

Mention of Mehragān is also made in a qaṣida by Abu’l-Moqātel Naṣr b. Noṣayr praising the victory of Moḥammad b. Zayd ʿAlawi, popularly known as al-Dāʿi al-Kabir (the Great Missionary), who conquered Māzandarān in 250/864:

Announce not only one but two pieces of good news,

The glory of the Dāʿi and the day of Mehragān!

It is a nomadic (badawi) moment in the time,

But the son of Zayd is the master of time’s servitude.

(Masʿudi, Moruj, sec. 2518)

The Arabic divān by the panegyrist of Persian origin Mehyār Deylami (worked in Baghdad in the first half of the 11th century) contains sixty-nine qaṣidas celebrating Mehragān, in some of which it is indicated as a culminating moment in the year (Mehyār Deylami, II, pp. 253–56; IV, pp. 60–62). Indeed, Mehragān is regarded as a sign of resurrection and the end of the world, for everything which grows then reaches its perfection (Biruni, Āṯār, p. 223; tr., p. 208).

The custom of a sovereign changing his clothing at this time is reported by Biruni (p. 223, tr. p. 209), who relates that the sultans of Khorasan arranged for the distribution of autumn and winter clothes to their soldiers at Mehragān.

His statement is corroborated by Ps.-Jāḥeẓ (Ketāb al-tāj, p. 150; tr., p. 169), who mentions the distribution of clothes at Nowruz and Mehragān by the Taherid amir ʿAbd-Allāh b. Ṭāher.

This custom, implying the renewal of personal belongings, is probably the only one of the Mehragān observances that has a minimal echo in contemporary Iran, outside of Zoroastrian circles; that is the custom of carpet washing (qāli-šuyān) found in Mašhad-e Ardahāl, near Kashan (see Āl-e Aḥmad, pp. 200–205; cf. Ruḥ-al-Amini, p. 85; on this festival and its customs, see ʿAẓimā).

A modern renewal of the Mehragān tradition may be noticed in the inauguration of the academic year at the University of Tehran, occurring sometimes on the 10th, some other times on the 16th of the month of Mehr.

Outside Iran itself, but still in an Iranian milieu, we can find traces of Mehragān in the memoirs of the Tajik modern writer Ṣadr-al-Din ʿAyni (q.v.). In connection with his native city of Gijduvan (Bukhara province, Uzbekistan), he describes entertainments such as para-military performances, fireworks, races, and animal fights (see Ruḥ-al-Amini, p. 85).

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mehragan

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Επιπλέον:

https://english.mojahedin.org/i/

— — — — — — — — — — — —

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

https://vk.com/doc429864789_620132611

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/ss-250611802

https://issuu.com/megalommatis/docs/mehragan_the_parsis_great_autumn_feast.docx

No comments:

Post a Comment