Babur (1483–1530): Military Genius, Philosopher, Poet, Historian, Emperor, Descendant of Tamerlane, Founder of the Gorkanian Dynasty from Central Asia to Hindustan, Bengal and the Dekkan

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 18η Σεπτεμβρίου 2019.

Ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης χρησιμοποιεί τμήμα πομιλίας μου, την οποία έδωσα στο Πεκίνο τον Ιανουάριο του 2019 με θέμα τους παράλληλους βίους μεγάλων στρατηλατών και αυτοκρατόρων των Ακκάδων, των Χιττιτών, των Ασσυρίων, των Ιρανών, των Ρωμαίων, των Τουρανών-Μογγόλων, και των Κινέζων.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/18/μπαμπούρ-1483-1530-στρατηλάτης-φιλόσοφος-πο/

=================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής — Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Αρκετοί φίλοι με ρώτησαν τελευταία για το Τατζ Μαχάλ, για την Ισλαμική Αυτοκρατορία των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων (Γκορκανιάν / Μουγάλ-Mughal) της Ινδίας, και τις σχέσεις των Σουνιτών Γκορκανιάν με τους Σιίτες Σαφεβίδες του Ιράν και τους Σουνίτες Οθωμανούς. Με δεδομένη την ιρανο-οθωμανική αντιπαλότητα (στην οποία αναφέρθηκα στα κείμενά μου σχετικά με την Μάχη του Τσαλντιράν το 1514), ένας φίλος με ρώτησε πως και δεν συμφώνησαν Οθωμανοί και Γκορκανιάν να μοιράσουν το Ιράν ανάμεσα στην Σταμπούλ και την Άγκρα.

Η απάντηση είναι απλή: σε μια εποχή που δεν υπήρχαν εθνικισμοί και που η Πίστη αποτελούσε τον βασικό (αλλά όχι τον μόνο) δείκτη ταυτότητας, οι φυλετικές διαφορές βάραιναν σημαντικά. Αν ανάμεσα σε δυο κλάδους της ίδιας φυλής είχε χυθεί αίμα, αυτό θα ήταν πολύ δύσκολο να ξεχαστεί ακόμη και εκατό χρόνια αργότερα.

Οθωμανοί, Σαφεβίδες του Ιράν, και Γκορκανιάν της Νότιας Ασίας (όχι μόνον ‘Ινδίας’) ήταν όλοι τουρκομογγολικής καταγωγής.

Οθωμανοί και Γκορκανιάν ήταν Σουνίτες, ενώ οι Σαφεβίδες ήταν Σιίτες.

Αλλά ο Ταμερλάνος, πρόγονος των Γκορκανιάν, είχε χύσει οθωμανικό αίμα το 1402 στην Μάχη της Άγκυρας. Αυτό ξεπεράστηκε σε κάποιο βαθμό αλλά δεν ξεχάστηκε ποτέ.

Η Ιστορία της Μογγολικής Αυτοκρατορίας της Νότιας Ασίας είναι γεμάτη από πλούτο, τέχνες, γράμματα, εντυπωσιακά μνημεία και μυστικισμό. Νομίζω ότι ο καλύτερος τρόπος για να την προσεγγίσει κάποιος είναι να μάθει μερικά βασικά στοιχεία για τον εντελώς ξεχωριστό άνθρωπο που ήταν ο ιδρυτής αυτής της δυναστείας. Παρά την μεταγενέστερη επέκταση των Γκορκανιάν, κανένας απόγονος του Μπαμπούρ δεν τον ξεπέρασε στην στρατιωτική τέχνη.

Έφηβος οδηγούσε εμπειροπόλεμα στρατεύματα στις μάχες. Για σχεδόν τρεις δεκαετίες διέσχισε όλα τα κακοτράχαλα βουνά ανάμεσα στο ιρανικό οροπέδιο, τις στέππες της Σιβηρίας, την Τάκλα Μακάν και τις κοιλάδες του Ινδού και του Γάγγη. Πριν κατακτήσει το Χιντουστάν (: σημερινή βόρεια Ινδία), άλλαζε βασίλεια σχεδόν σαν τα πουκάμισα. Παράλληλα, συνέγραφε ιστορικά κείμενα και ποιήματα, έπινε, χαιρόταν την ζωή, και διερχόταν περιόδους ασκητισμού.

Παρά το ότι ο μεγάλος θρίαμβος ήλθε στο τέλος, ο Μπαμπούρ δεν ξέχασε ποτέ την γη που του συμπαραστάθηκε στα χρόνια των δοκιμασιών: την Καμπούλ του σημερινού Αφγανιστάν. Έτσι, αν και πέθανε στην Άγκρα της Ινδίας, θέλησε να ταφεί στην Καμπούλ. Ένας τεράστιος κήπος περιβάλλει το μαυσωλείο του Μπαμπούρ και μπορείτε να το δείτε σε δυο βίντεο, στις εισαγωγές των οποίων δίνω ένα γενικό σχεδιάγραμμα της ζωής και των ενδιαφερόντων, των κατορθωμάτων και των μαχών του Τίγρη (Μπαμπούρ σημαίνει Τίγρης στα τσαγατάι τουρκικά που ήταν η μητρική του γλώσσα κι αυτή των στρατιωτών του).

Κήποι και Μαυσωλείο του Μπαμπούρ στην Καμπούλ του Αφγανιστάν

Στο θέμα θα επανέλθω για να επεκταθώ στο Μπαμπούρ Ναμέ, το ‘Βιβλίο του Μπαμπούρ’ το οποίο συνέγραψε ο ίδιος ο στρατηλάτης και αυτοκράτορας. Το αντίστοιχο θα υπήρχε, αν συγχωνεύονταν σε ένα πρόσωπο ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος και ο Αρριανός, ή ο Ιουστινιανός και ο Προκόπιος.

Μπορείτε να δείτε και αλλοιώς: το Μπαμπούρ Ναμέ είναι το ανατολικό, ασιατικό De Bello Civili και De Bello Gallico. Ή, πιο απλά, ο Μπαμπούρ είναι ο Μογγόλος Καίσαρ. Αλλά ο Καίσαρ είχε μόνιμο σημείο αναφοράς την Ρώμη. Ο Μπαμπούρ μετεκινείτο ως βασιλιάς από την Φεργάνα στην Σαμαρκάνδη, από κει στην Καμπούλ και τελικά στην Άγκρα. Δεν όριζε το στέμμα του το σπαθί του, αλλά το σπαθί του το στέμμα του.

Νόμισμα που έκοψε ο Μπαμπούρ το 1507–1508

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Кабул: Сады и Мавзолей Бабура, Могольского Императора (Горкани) Индии

https://www.ok.ru/video/1509854481005

Περισσότερα:

Баги Бабур (пушту باغ بابر, перс. باغ بابر; также встречаются названия сад Бабура и сады Бабура) — парковый комплекс в Афганистане, расположен неподалеку от города Кабула. Назван в честь своего владельца Бабура, основателя империи Великих Моголов. Бабур, помимо этого, увлекался разведением садов. Баги Бабур является одной из достопримечательностей страны. Отличается тщательной продуманностью посадок; в прошлом в нём выращивались многие уникальные растения. Среди них были различные сорта фруктов, бахчевых и многое другое, что ранее вовсе не встречалось на данной территории.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Баги_Бабур

The Garden of Babur (locally called Bagh-e Babur, Persian: باغ بابر / bāġ-e bābur) is a historic park in Kabul, Afghanistan, and also the last resting-place of the first Mughal emperor Babur. The garden are thought to have been developed around 1528 AD (935 AH) when Babur gave orders for the construction of an “avenue garden” in Kabul, described in some detail in his memoirs, the Baburnama.

The original construction date of the gardens (Persian: باغ — bāġ) is unknown. When Babur captured Kabul in 1504 from the Arguns he re-developed the site and used it as a guest house for special occasions, especially during the summer seasons. Since Babur had such a high rank, he would have been buried in a site that befitted him. The garden where it is believed Babur requested to be buried in is known as Bagh-e Babur. Mughul rulers saw this site as significant and aided in further development of the site and other tombs in Kabul. In an article written by the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, describes the marble screen built around tombs by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in 1638 with the following inscription:

“only this mosque of beauty, this temple of nobility, constructed for the prayer of saints and the epiphany of cherubs, was fit to stand in so venerable a sanctuary as this highway of archangels, this theatre of heaven, the light garden of the god forgiven angel king whose rest is in the garden of heaven, Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur the Conqueror.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gardens_of_Babur

Ένα από τα πιο ενδιαφέροντα μνημεία της Καμπούλ είναι οι τεράστιοι κήποι και το μαυσωλείο του απογόνου του Ταμερλάνου βασιλιά της Φεργκάνα (σήμερα στο Ουζμπεκιστάν), ο οποίος αφού κατέκτησε την Σαμαρκάνδη, το σημερινό ανατολικό Ιράν και την Καμπούλ, κατέλαβε την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού και όλη την Ινδία (Χιντουστάν: σημερινή βόρεια Ινδία).

Εκεί κατέλυσε το ισλαμικό Σουλτανάτο του Δελχίου, θεμελίωσε την Αυτοκρατορία των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων (Μουγάλ — Mughal, όπως είναι γνωστοί στις δυτικές γλώσσες) την οποία οι ίδιοι αποκαλούσαν Γκορκανιάν.

Η λέξη αυτή (گورکانیان, Gūrkāniyān) είναι περσική και σημαίνει ‘Γαμπροί’. Έτσι ονόμαζαν τους Μεγάλους Μογγόλους της Νότιας Ασίας οι Ιρανοί στα φαρσί (περσικά) επειδή οι Μεγάλοι Μογγόλοι διατήρησαν την μογγολική παράδοση να ανεβαίνει στον θρόνο και γενικώτερα στην ιεραρχία της αυτοκρατορίας ένας ταπεινής καταγωγής αλλά γενναίος στρατιωτικός μετά από τον γάμο του με μια από τις κόρες ενός ευγενή ή ενός αυτοκράτορα.

Ο Μπαμπούρ ήταν μια στρατιωτική μεγαλοφυία, ένας πολυμαθής φιλόσοφος, ένας ποιητής και ιστορικός που άφησε ένα τεράστιο βιογραφικό ιστορικό έργο γραμμένο σε τσαγατάι τουρκικά με αρκετούς περσισμούς που λέγεται Μπαμπούρ Ναμέ (το Βιβλίο του Μπαμπούρ).

Η Ισλαμική (Σουνιτική) Αυτοκρατορία των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων ήταν συχνά ισχυρώτερη και πλουσιώτερη από την Σαφεβιδική (Σιιτική) Αυτοκρατορία του Ιράν και την Οθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, συνένωσε εκτάσεις από την Κεντρική Ασία μέχρι την Ινδονησία, προξένησε μια μεγάλη μετανάστευση τουρκομογγολικών πληθυσμών στην Ινδία και στο Ντεκάν, κι αποτελεί την περίοδο της μεγαλύτερης ανάπτυξης Γραμμάτων, Τεχνών και Πολιτισμού στην Ινδία, το Ντεκάν, και γενικώτερα στην Νότια Ασία.

Ωστόσο, οι Γκορκανιάν είχαν έντονα επηρεαστεί από τον ιρανικό πολιτισμό.

Στην αυτοκρατορία τους, τα περσικά ήταν η γλώσσα της τέχνης και της λογοτεχνίας, τα αραβικά η γλώσσα των επιστημών, και τα ουρντού η γλώσσα του στρατού.

Τα ουρντού είναι στη βάση τους μια τουρκική γλώσσα (σήμερα στα τουρκικά της Τουρκίας ordu σημαίνει ‘στρατός’) μεικτή με ινδοευρωπαϊκό λεξιλόγιο.

Αν και πέθανε και τάφηκε στην βόρεια Ινδία ο Μπαμπούρ (στα τουρκικά το όνομά του σημαίνει ‘Τίγρης’), ζήτησε να ταφεί σε μια πόλη που του χρησίμευσε ως βάση για την κατάκτηση της βόρειας Ινδίας.

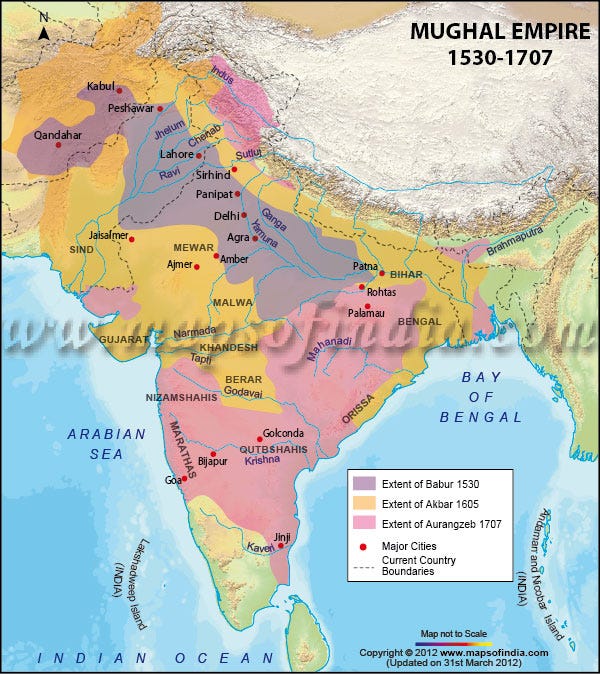

Γενικό σχεδιάγραμμα της πορείας του Μπαμπούρ από την Κεντρική Ασία προς την Ινδία

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Kabul: Gardens and Mausoleum of Babur, Mughal Emperor (Gorkani) of India

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240305

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Καμπούλ: Κήποι και Μαυσωλείο του Μπαμπούρ, Μεγάλου Μογγόλου (Γκορκανιάν) Αυτοκράτορα της Ινδίας

===============

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Бабур (1483–1530): военный гений, поэт, историк и император, основатель Горканской династии (Великих Моголов) Индии

https://www.ok.ru/video/1510072388205

Περισσότερα:

Захир-ад-дин Мухаммад Бабу́р (узб. Zahiriddin Muhammad Bobur; араб. ﻇَﻬﻴﺮْ ﺍَﻟَﺪّﻳﻦ مُحَمَّدْ بَابُرْ, «Бабур» означает «лев, полководец, барс» и происходит от персидского слова ْبَبْر (babr) — «тигр», 14 февраля 1483–26 декабря 1530) — среднеазиатский и тимуридский правитель Индии и Афганистана, полководец, основатель династии и империи Бабуридов, в некоторых источниках — как империи Великих Моголов (1526). Известен также как узбекский поэт и писатель.

Полная тронная титулатура: ас-Султан аль-Азам ва-л-Хакан аль-Мукаррам Захир ад-дин Мухаммад Джалал ад-дин Бабур, Падшах-и-Гази.

Бабур — основатель династии, выходец из города Андижан. Родным языком Бабура был турки (староузбекский). Писал в своих мемуарах: “Жители Андижана — все тюрки; в городе и на базаре нет человека, который бы не знал по-тюркски. Говор народа сходен с литературным”. “Мемуары Бабура написаны на той разновидности тюркского языка, которая известна под названием турки, являющегося родным языком Бабура”, — писал английский востоковед Е. Дениссон Росс.

За свою 47-летнюю жизнь Захириддин Мухаммад Бабур оставил богатое литературное и научное наследие. Его перу принадлежит знаменитое «Бабур-наме», снискавшая мировое признание, оригинальные и прекрасные лирические произведения (газели, рубаи), трактаты по мусульманскому законоведению («Мубайин»), поэтике («Аруз рисоласи»), музыке, военному делу, а также специальный алфавит «Хатт-и Бабури».

Бабур переписывался с Алишером Навои. Стихи Бабура, написанные на тюркском, отличаются чеканностью образов и афористичностью. Главный труд Бабура — автобиография «Бабур-наме», первый образец этого жанра в исторической литературе, излагает события с 1493 по 1529 годы, живо воссоздаёт детали быта знати, нравы и обычаи эпохи. Французский востоковед Луи Базан в своём введении к французскому переводу (1980 г.) писал, что «автобиография (Бабура) представляет собой чрезвычайно редкий жанр в исламской литературе».

В последние годы жизни тема потери Родины стала одной из центральных тем лирики Бабура. Заслуга Бабура как историка, географа, этнографа, прозаика и поэта в настоящее время признана мировой востоковедческой наукой. Его наследие изучается почти во всех крупных востоковедческих центрах мира.

Можно сказать, что стихи Бабура — автобиография поэта, в которых поэтическим языком, трогательно излагаются глубокие чувства, мастерски рассказывается о переживаниях, порожденных в результате столкновения с жизненными обстоятельствами, о чём красноречиво говорит сам поэт:

Каких страданий не терпел и тяжких бед, Бабур?

Каких не знал измен, обид, каких клевет, Бабур?

Но кто прочтет «Бабур-наме», увидит, сколько мук

И сколько горя перенес царь и поэт Бабур.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Бабур

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Babur (1483–1530): Military Genius, Poet, Historian and Emperor, the Founder of the Gorkanian Dynasty (Great Mughal) of India

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240306

Περισσότερα:

Babur (Persian: بابر, romanized: Bābur, lit. ‘tiger’] 14 February 1483–26 December 1530), born Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad, was the founder and first Emperor of the Mughal dynasty in South Asia. He was a direct descendant of Emperor Timur (Tamerlane) from what is now Uzbekistan.

The difficulty of pronouncing the name for his Central Asian Turco-Mongol army may have been responsible for the greater popularity of his nickname Babur, also variously spelled Baber, Babar, and Bābor The name is generally taken in reference to the Persian babr, meaning “tiger”. The word repeatedly appears in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and was borrowed into the Turkic languages of Central Asia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babur#Ruler_of_Central_Asia

Захир-ад-дин Мухаммад Бабу́р (узб. Zahiriddin Muhammad Bobur; араб. ﻇَﻬﻴﺮْ ﺍَﻟَﺪّﻳﻦ مُحَمَّدْ بَابُرْ, «Бабур» означает «лев, полководец, барс» и происходит от персидского слова ْبَبْر (babr) — «тигр», 14 февраля 1483–26 декабря 1530) — среднеазиатский и тимуридский правитель Индии и Афганистана, полководец, основатель династии и империи Бабуридов, в некоторых источниках — как империи Великих Моголов (1526). Известен также как узбекский поэт и писатель. Полная тронная титулатура: ас-Султан аль-Азам ва-л-Хакан аль-Мукаррам Захир ад-дин Мухаммад Джалал ад-дин Бабур, Падшах-и-Гази.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Бабур

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Μπαμπούρ (1483–1530): Στρατηλάτης, Ποιητής, Ιστορικός, Πρώτος Αυτοκράτορας των Γκορκανιάν της Ινδίας

Περισσότερα:

Ένας από τους μεγαλύτερους στρατηλάτες όλων των εποχών, ένας από τους ελάχιστους ηγεμόνες που δεν έχασαν ποτέ μάχη, ένας στρατιωτικός με μεγάλη μάθηση, γνώση και σοφία, συγγραφέας ενός μεγαλειώδους ιστορικού έργου (Μπαμπούρ Ναμέ: ‘το Βιβλίο του Μπαμπούρ’), ποιητής και μυστικιστής, με ενδιαφέρον για την καλοζωΐα σε σύντομα όμως χρονικά διαστήματα αλλά και με ασκητικές τάσεις, ήταν ο θεμελιωτής της μεγάλης μογγολικής δυναστείας της Νότιας Ασίας που οι δυτικοί αποκαλούν Μουγάλ (Μεγάλους Μογγόλους).

Όταν ο Μπαμπούρ γεννήθηκε στο Αντιτζάν της Κοιλάδας Φεργάνα της Κεντρικής Ασίας (σήμερα στο Ουζμπεκιστάν), τίποτα δεν έδειχνε ότι θα γινόταν ό ίδιος ο ιδρυτής μιας τεράστιας αυτοκρατορίας.

Απόγονος του Ταμερλάνου, ήταν γιος του ηγεμόνα ενός μικρού από τα πολλά τιμουριδικά βασίλεια των χρόνων του.

Έμεινε ορφανός και συνεπώς ηγεμόνας ενός μικρού βασιλείου στα 11 του χρόνια. Ακολούθησαν τρεις τρομερές δεκαετίες στην διάρκεια των οποίων ο Μπαμπούρ άλλαξε τον χάρτη της Κεντρικής και της Νότιας Ασίας.

Ήταν μια σειρά πολέμων, κατακτήσεων και διαδοχικών βασιλείων από τα οποία ο ίδιος με τους στρατιώτες του μετεκινούνταν, συχνά εν μέσω φονικών μαχών, τρομερών κακουχιών και φυσικών αντιξοοτήτων.

Μόνον στα 43 του, το 1526, κατάφερε ο Μπαμπούρ επιτέλους να επιβληθεί στην βόρεια Ινδία και να θεμελιώσει την δυναστεία — θρύλο της Νότιας Ασίας.

Έτσι, ο Μπαμπούρ διαδοχικά χρημάτισε:

1494–1497: βασιλιάς της Φεργάνα

1497–1498: βασιλιάς της Σαμαρκάνδης

1498–1500: βασιλιάς της Φεργάνα

1500–1501: βασιλιάς της Σαμαρκάνδης

1504–1530: βασιλιάς της Καμπούλ

1511–1512: βασιλιάς της Σαμαρκάνδης

1526–1530: αυτοκράτορας του Χιντουστάν (πρωτεύουσα: Άγκρα)

Οι μάχες του Πανιπάτ (1526), της Χάνουα (1527), και του Τσαντερί (1528) στερέωσαν την κυριαρχία του στην βόρεια Ινδία (Χιντουστάν).

Μέχρι τότε, αν και σουνίτης μουσουλμάνος, δεν δίστασε να συνεργαστεί με τους Κιζιλμπάσηδες (όταν ο Οθωμανός Σουλτάνος Σελίμ Α’ προτίμησε να συνεργαστεί με τους Ουζμπέκους εχθρούς του), με τον Σάχη Ισμαήλ Α’ (βασ. 1501–1524), και στην συνέχεια (μετά το 1513) με τον Σελίμ Α’ (βασ. 1512–1520), ο οποίος νωρίς κατάλαβε ότι ο Μπαμπούρ θα μπορούσε να στήσει ό,τι χρειαζόταν η Οθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία: μια μεγάλη σουνιτική ισλαμική αυτοκρατορία από την άλλη, ανατολική, πλευρά των συνόρων της σιιτικής ισλαμικής ιρανικής αυτοκρατορίας των Σαφεβιδών.

Αυτό ήταν μεγάλος ρεαλισμός: το 1402 (ένα αιώνα νωρίτερα) ο Βαγιαζίτ Α’, πρόγονος του Σελίμ Α’, είχε συλληφθεί αιχμάλωτος από τον Ταμερλάνο (πρόγονο του Μπαμπούρ), ο οποίος είχε χύσει άφθονο οθωμανικό αίμα στην Μάχη της Άγκυρας.

Ωστόσο, οι Γκορκανιάν (όπως αποκαλούνταν οι Μεγάλοι Μογγόλοι οι ίδιοι στα περσικά) κράτησαν μια ισορροπία στις σχέσεις τους ανάμεσα σε Σαφεβίδες και Οθωμανούς.

Πριν από 500 χρόνια, ο Σουλτάνος Σελίμ Α’ (1470–1520), ο Σάχης Ισμαήλ Α’ (1487–1524), και ο Μπαμπούρ (1483–1530) ήταν οι τρεις ισχυρώτεροι αυτοκράτορες του κόσμου.

Και ήταν, ασχέτως θρησκευτικών διαφορών, και οι τρεις τουρκομογγολικής καταγωγής.

Με περισσότερη κλίση στην θεολογία και στην στρατιωτική πειθαρχία ο πρώτος, με έντονη τάση στην ποίηση και την συγγραφή οι άλλοι δύο που επίσης διέπρεπαν και στον έκλυτο βίο — ο Ισμαήλ Α’ συνεχώς κι ο Μπαμπούρ περιστασιακά.

Ο Μπαμπούρ θυμίζει τον Μεγάλο Αλέξανδρο: αλλού γεννήθηκε (Φεργάνα), αλλού πέθανε (Χιντουστάν), αλλού τάφηκε (Καμπούλ).

Ο τάφος του Μπαμπούρ στην Καμπούλ του Αφγανιστάν

=============================

Μικρό τζαμί δίπλα στο μαυσωλείο του Μπαμπούρ

Διαβάστε:

Bābor, Ẓahīr-al-dīn Moḥammad

(6 Moḥarram 886–6 Jomādā I 937/14 February 1483–26 December 1530) Timurid prince, military genius, and literary craftsman who escaped the bloody political arena of his Central Asian birthplace to found the Mughal Empire in India

His origin, milieu, training, and education were steeped in Persian culture and so Bābor was largely responsible for the fostering of this culture by his descendants, the Mughals of India, and for the expansion of Persian cultural influence in the Indian subcontinent, with brilliant literary, artistic, and historiographical results.

Bābor’s father, ʿOmar Šayḵ Mīrzā (d. 899/1494), ruled the kingdom of Farḡāna along the headwaters of the Syr Darya, but as one of four brothers, direct fifth-generation descendants from the great Tīmūr, he entertained larger ambitions. The lack of a succession law and the presence of many Timurid males perpetuated an atmosphere of constant intrigue, often erupting into open warfare, between the descendants who vied for mastery in Khorasan and Central Asia, but they finally lost their patrimony when they proved incapable of cooperating to defend it against a common enemy.

It was against that same enemy, namely, the Uzbeks under the brilliant Šaybānī Khan (d. 916/1510), that Bābor himself learned his trade as a military leader in a long series of losing encounters. Bābor’s mother, Qotlūk Negār Ḵanūm, was the daughter of Yūnos Khan of Tashkent and a direct descendant of Jengiz Khan. She and her mother, Aysān-Dawlat Bēgam, had great influence on Bābor during his early career. It was his grandmother, for instance, who taught Bābor many of his political and diplomatic skills (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 43), thus initiating the long series of contributions by strong and intelligent women in the history of the Mughal Empire.

Ο Μπαμπούρ (δεξιά) με τον γιο και διάδοχό του Χουμαγιούν

Bābor presumed that his descent from Tīmūr legitimized his claim to rule anywhere that Tīmūr had conquered, but like his father, the first prize he sought was Samarqand. He was plunged into the maelstrom of Timurid politics by his father’s death in Ramażān, 899/June, 1494, when he was only eleven. Somehow he managed to survive the turbulent years that followed. Wars with his kinsmen, with the Mughals under Tanbal who ousted him from Andijan, the capital city of Farḡāna, and especially with Šaybānī Khan Uzbek mostly went against him, but from the beginning he showed an ability to reach decisions quickly, to act firmly and to remain calm and collected in battle. He also tended to take people at their word and to view most situations optimistically rather than critically.

Ο Μπαμπούρ (έφιππος αριστερά) με τον Τιμουρίδη πρίγκηπα της Σαμαρκάνδης Σουλτάν Αλί Μιρζά

In Moḥarram, 910/June-July, 1504, at the age of twenty-one, Bābor, alone among the Timurids of his generation, opted to leave the Central Asian arena, in which he had lost everything, to seek a power base elsewhere, perhaps with the intention of returning to his homeland at a later date.

Accompanied by his younger brothers, Jahāngīr and Nāṣer, he set out for Khorasan, but changed his plans and seized the kingdom of Kabul instead.

In this campaign he began to think more seriously of his role as ruler of a state, shocking his troops by ordering plunderers beaten to death (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 197).

The mountain tribesmen in and around Farḡāna with whom Bābor had frequently found shelter had come to accept him as their legitimate king.

He had no such claims upon the loyalty of the Afghan tribes in Kabul, but he had learned much about human nature and the nomad mentality in his three prolonged periods of wandering among the shepherd tribes of Central Asia (during 903/1497–98, 907/1501–02, and 909/1503–04).

He crushed all military opposition, even reviving the old Mongol shock tactic of putting up towers of the heads of slain foes, but he also made strenuous efforts to be fair and just, admitting, for instance, that his early estimates of food production and hence the levy of tributary taxes were excessive (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 228).

At this point Bābor still saw Kabul as only a temporary base for re-entry to his ancestral domain, and he made several attempts to return in the period 912–18/1506–12. In 911/1505 his uncle Sultan Ḥosayn Mīrzā of Herat, the only remaining Timurid ruler besides Bābor, requested his aid against the Uzbeks — even though he himself had refused to aid Bābor on several previous occasions.

His uncle died before Bābor arrived in Herat, but Bābor remained there till he became convinced that his cousins were incapable of offering effective resistance to Šaybānī Khan’s Uzbeks.

While in Herat he sampled the sophistication of a brilliant court culture, acquiring a taste for wine, and also developing an appreciation for the refinements of urban culture, especially as exemplified in the literary works of Mīr ʿAlī-Šīr Navāʾī.

During his stay in Herat Bābor occupied Navāʾī’s former residence, prayed at Navāʾī’s tomb, and recorded his admiration for the poet’s vast corpus of Torkī verses, though he found most of the Persian verses to be “flat and poor” (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 272).

Navāʾī’s pioneering literary work in Torkī, much of it based, of course, on Persian models, must have reinforced Bābor’s own efforts to write in that medium.

Ο Μπαμπούρ βλέπει τα αγάλματα των Τζαϊνιστών στο Γκουάλιορ.

In Rajab, 912/December, 1506, Bābor returned to Kabul in a terrible trek over snow-choked passes, during which several of his men lost hands or feet through frostbite. The event has been vividly described in his diary (Bābor-nāma, tr., pp. 307–11). As he had foreseen, the Uzbeks easily took Herat in the following summer’s campaign, and Bābor indulged in one of his rare slips from objectivity when he recorded the campaign in his diary with some unfair vilification of Šaybānī Khan, his long-standing nemesis (Bābor-nāma, tr., pp. 328–29).

Bābor next consolidated his base in Kabul, and added to it Qandahār. He dramatically put down a revolt by defeating, one by one in personal combat, five of the ringleaders — an event which his admiring young cousin Mīrzā Moḥammad Ḥaydar Doḡlat believed to be his greatest feat of arms (Tārīḵ-erašīdī, tr., p. 204).

Here again it seems that Bābor acted impetuously, but saved himself by his courage and strength; and such legend-making deeds solidified his charismatic hold on the men whom he had to lead in battle. Uncharacteristically, Bābor withdrew from Qandahār and Kabul at the rumor that Šaybānī Khan was coming.

It was apparently the only time in his life when he lost confidence in himself. In fact, the Uzbek leader was defeated and killed by Shah Esmāʿīl Ṣafawī in 916/1510, and this opened the way for Bābor’s last bid for a throne in Samarqand.

From Rajab, 917 to Ṣafar, 918/October, 1511 to May, 1512, he held the city for the third time, but as a client of Shah Esmāʿīl, a condition that required him to make an outward profession of the Shiʿite faith and to adopt the Turkman costume of the Safavid troops.

Bābor’s kinsmen and erstwhile subjects did not concur with his doctrinal realignment, however much it had been dictated by political circumstances. Moḥammad-Ḥaydar, a young man indebted to Bābor for both refuge and support, exulted at the Uzbek defeat of Bābor, thus demonstrating how unusual in that time and place were Bābor’s breadth of vision and tolerance, qualities that became crucial to his later success in India. Breaking away from his Safavid allies, Bābor dallied in the Qunduz area, but he must have sensed that his chance to regain Samarqand was irretrievably lost.

Ο Μπαμπούρ παρατηρεί τους εργάτες να αλλάζουν το ρεύμα ενός ποταμού.

It was only at this stage that he began to think of India as a serious goal, though after the conquest he wrote that his desire for Hindustan had been constant from 910/1504 (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 478). With four raids beginning in 926/1519, he probed the Indian scene and discovered that dissension and mismanagement were rife in the Lodi Sultanate. In the winter of 932/1525–26 he brought all his experience to bear on the great enterprise of the conquest of India. With the proverb “Ten friends are better than nine” in mind, he waited for all his allies before pressing his attack on Lahore (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 433).

His great skills at organization enabled him to move his 12,000 troops from 16 to 22 miles a day once he had crossed the Indus, and with brilliant leadership he defeated three much larger forces in the breathtaking campaigns that made him master of North India. First he maneuvered Sultan Ebrāhīm Lōdī into attacking his prepared position at the village of Panipat north of Delhi on 8 Rajab 932/20 April 1526. Although the Indian forces (he estimated them at 100,000; Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 480) heavily outnumbered Bābor’s small army, they fought as a relatively inflexible and undisciplined mass and quickly disintegrated.

Bābor considered Ebrāhīm to be an incompetent general, unworthy of comparison with the Uzbek khans, and a petty king, driven only by greed to pile up his treasure while leaving his army untrained and his great nobles disaffected (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 470). Yet Bābor ordered a tomb to be built for him.

He then swiftly occupied Delhi and Agra, first visiting the tombs of famous Sufi saints and previous Turkish kings, and characteristically laying out a garden.

The garden provided him with such satisfaction that he later wrote: “to have grapes and melons grown in this way in Hindustan filled my measure of content” (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 686).

His new kingdom was a different story. Bābor first had to solve the problem of disaffection among his troops.

Like Alexander’s army, they felt that they were a long way from home in a strange and unpleasant land.

Bābor had planned the conquest intending to make India the base of his empire since Kabul’s resources proved too limited to support his nobles and troops.

He himself never returned to live in Kabul.

But, since he had permitted his troops to think that this was simply another raid for wealth and booty, he had to persuade them otherwise, which was no easy chore (Bābor-nāma, tr., pp. 522–35).

The infant Mughal state also had to fight for its life against a formidable confederation of the Rajput chiefs led by Mahārānā Sangā of Mewar.

After a dramatic episode in which Bābor publicly foreswore alcohol (Bābor-nāma, tr., pp. 551–56), Bābor defeated the Rajputs at Khanwah on 13 Jomādā I 933/17 March 1527 with virtually the same tactics he had used at Panipat, but in this case the battle was far more closely contested.

Bābor next campaigned down the Ganges River to Bengal against the Afghan lords, many of whom had refused to support Ebrāhīm Lōdī but also had no desire to surrender their autonomy to Bābor.

Even while rival powers threatened him on all sides — Rajputs and Afghans in India, Uzbeks at his rear in Kabul — Bābor’s mind was turned to consolidation and government.

He employed hundreds of stone masons to build up his new capital cities, while winning over much of the Indian nobility with his fair and conciliatory policies.

He was anxiously grooming his sons to succeed him, not without some clashes of personality, when his eldest son Homāyūn (b. 913/1506) fell seriously ill in 937/1530.

Another young son had already died in the unaccustomed Indian climate, and at this family crisis his daughter Golbadan wrote that Bābor offered his own life in place of his son’s, walking seven times around the sickbed to confirm the vow (Bābor-nāma, translator’s note, pp. 701–2).

Bābor did not leave Agra again, and died there later that year on 6 Jomādā I 937/26 December 1530.

Ο Μπαμπούρ διασχίζει κολυμπώντας τον Ινδό ποταμό στην διάρκεια μάχης.

Bābor’s diary, which has become one of the classic autobiographies of world literature, would be a major literary achievement even if the life it illuminates were not so remarkable. He wrote not only the Bābor-nāma but works on Sufism, law and prosody as well as a fine collection of poems in Čaḡatay Torkī. In all, he produced the most significant body of literature in that language after Navāʾī, and every piece reveals a clear, cultivated intelligence as well as an enormous breadth of interests.

His Dīvān includes a score or more of poems in Persian, and with the long connection between the Mughals and the Safavid court begun by Bābor himself, the Persian language became not only the language of record but also the literary vehicle for his successors. It was his grandson Akbar who had the Bābor-nāma translated into Persian in order that his nobles and officers could have access to this dramatic account of the dynasty’s founder.

Bābor did not introduce artillery into India — the Portuguese had done that — and he himself noted that the Bengal armies had gunners (Bābor-nāma, tr., pp. 667–74). But his use of new technology was characteristic of his enquiring mind and enthusiasm for improvement. His Ottoman experts had only two cannons at Panipat, and Bābor personally witnessed the casting of another, probably the first to be cast in India, by Ostād ʿAlīqolī on 22 October 1526 (Bābor-nāma, tr., pp. 536–37).

The piece did not become ready for test firing till 10 February 1527 when it shot stones about 1,600 yards, and during the subsequent campaigns against the Afghans down the Ganges, Bābor specifically mentions Ostād ʿAlīqolī getting off eight shots on the first day of the battle and sixteen on the next (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 599). Quite obviously then it was not some technical superiority in weaponry, but Bābor’s genius in using the discipline and mobility which he had created in his troops that won the crucial battles for him in India.

Bābor, however, was generally interested in improving technology, not only for warfare but also for agriculture. He tried to introduce new crops to the Indian terrain and to spread the use of improved water-lifting devices for irrigation (Bābor-nāma, tr., p. 531). His interest in improvement and change was facilitated by his generous nature. Though he had faults, they were outweighed by his attractive personality, cheerful in the direst adversity, and faithful to his friends.

The loyalties he inspired enabled the Mughal Empire in India to survive his own early death and the fifteen-year exile of his son and successor, Homāyūn. The liberal traditions of the Mughal dynasty were Bābor’s enduring legacy to his country by conquest.

Τις βιβλιογαφικές παραπομπές του κειμένου θα βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/babor-zahir-al-din

Κήποι και Μαυσωλείο του Μπαμπούρ στην Καμπούλ του Αφγανιστάν και στιγμιότυπα από εκεί εκδηλώσεις

==============================

Επιπλέον:

Μπαμπούρ και Γκορκανιάν (Μεγάλοι Μογγόλοι):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babur

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Бабур

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mughal_Empire

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Империя_Великих_Моголов

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gardens_of_Babur

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Баги_Бабур

Οικογενειακό υπόβαθρο:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umar_Shaikh_Mirza_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qutlugh_Nigar_Khanum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu_Sa%27id_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timurid_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chagatai_Khanate

Τοπογραφικά για την καταγωγή του Μπαμπούρ:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fergana_Valley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fergana

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akhsikath

Ιστορικό υπόβαθρο:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kara-Khanid_Khanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khwarazmian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mongol_conquest_of_Khwarezmia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilkhanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hulagu_Khan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_Ilkhanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jalairid_Sultanate

Η μάχη του Πανιπάτ το 1526

Η Ινδία και το Ντεκάν στις παραμονές της κατάληψής τους από τον Μπαμπούρ. Η κυριαρχία του Ισλαμικού Σουλτανάτου του Δελχί περιοριζόταν στον βορρά, την καθαυτό Ινδία (Χιντουστάν). Ο υπόλοιπος χώρος σχεδόν όλος (που λέγεται Ντεκάν και όχι Ινδία) ήταν διαιρεμένος σε δραβιδικά βασίλεια που συνεχώς πολεμούσαν μεταξύ τους.

Πλατεία Μπαμπούρ στο Αντιτζάν του Ουζμπεκιστάν

— — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/14831530

https://issuu.com/megalommatis/docs/babur.docx

No comments:

Post a Comment