March 20, 1739: The Turkmen Nader Shah of Iran occupies Delhi, the Opulent Capital of the Gorkanian, i.e. the Formidable Mongols of ‘India’

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 20η Μαρτίου 2019.

Στο κείμενό του αυτό, ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης ενσωματώνει τμήματα δύο ομιλιών μου, οι οποίες δόθηκαν τον Ιανουάριο του 2019 στο Πεκίνο σχετικά με την γεωστρατηγική του αφρο-ευρασιατικού χώρου, την πτώση των μεγάλων ιστορικών αυτοκρατοριών, και την δυναμική μιας αυτοκρατορικής-οικουμενιστικής επιστροφής στην Γη.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/08/04/20-μαρτίου-1739-ο-τουρκμένος-ναντέρ-σάχης-το/

====================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής — Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Μια φορά όταν είπαν στον Ναντέρ ότι δεν υπάρχει πόλεμος στον Παράδεισο, λέγεται ότι ρώτησε: “Μπορεί να υπάρχει ευχαρίστηση εκεί”;

Πριν από 280 χρόνια, το αδιανόητο έγινε γεγονός! Το (σιιτικό) Ιράν κατέλαβε την (σουνιτική) Ισλαμική Αυτοκρατορία των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων (Μουγάλ), η οποία ήταν ένα πολύ μεγαλύτερο, πολυπληθέστερο και πλουσιώτερο κράτος. Καμμιά χώρα στον κόσμο δεν είχε ποτέ κατακτήσει την Κοιλάδα του Γάγγη. Αλλά για τον Αφσάρ Τουρκμένο γεωργό — πολεμιστή Ναντέρ όλα ήταν δυνατά!

Οι Αχαιμενιδείς είχαν κατακτήσει όλες τις εκτάσεις από την Μακεδονία μέχρι την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού, από τα βόρεια παράλια της Μαύρης Θάλασσας μέχρι το Σουδάν, κι από την Κεντρική Ασία μέχρι το Ομάν. Αλλά εκεί που τελειώνει η Πενταποταμία (Παντζάμπ: ‘Πέντε Ποτάμια’ στα φαρσί και στα ουρντού) τερματίζονταν και τα ανατολικά όρια του Ιράν.

Ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος που άτρομος διεξήγαγε και νικούσε σε μάχες έναντι συντριπτικά υπερτέρων δυνάμεων δεν κατέλαβε ‘πολλές’ χώρες! Αυτό είναι κάτι που πολλοί ξεχνούν στην Ελλάδα. Ουσιαστικά , ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος κατέκτησε μία χώρα: το Ιράν. Απέραντη, τεράστια, με πολυπληθή στρατεύματα, ναι! Αλλά μία. Ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος προχώρησε πέραν της Πενταποταμίας και νίκησε τον Πώρο, βασιλιά ενός βόρειου ινδικού βασιλείου. Και θα προχωούσε περισσότερο αλλά ξεσηκώθηκαν οι στρατιώτες του και τον απέτρεψαν.

Ι. Δεν υπάρχει ‘Ινδία’: είναι ένας ψεύτικος, αποικιοκρατικός, οριενταλιστικός όρος

Υπάρχει στο σημείο αυτό μια σύγχυση που δημιουργήθηκε από αρχαίους Έλληνες και Ρωμαίους συγγραφείς: προερχόμενος από το όνομα του Ινδού ποταμού, ο όρος ‘Ινδία’ (Χεντ και Σιντ) απέκτησε σιγά-σιγά μια τεράστια ασάφεια, ακριβώς επειδή η γνώση για εκτάσεις πέραν του ποταμού ήταν μικρή.

Τα βασίλεια ανατολικά του Ινδού αποτελούσαν βέβαια την Ινδία και ήταν εθνοφυλετικά συγγενή προς τους Πέρσες και τους Άρειους, αλλά πιο πέρα στα ανατολικά και στα νότια εκτείνονταν δραβιδικά βασίλεια που δεν είχαν καμμιά συγγένεια — εθνική, γλωσσική, πολιτισμική — με τους πραγματικούς Ινδούς των βασιλείων αμέσως ανατολικά του Ινδού. Οι Δραβίδες είναι τόσο διαφορετικοί από τους Ινδούς όσο οι Έλληνες από τους Κινέζους.

Στα χρόνια της Ύστερης Αρχαιότητας, ο αρχαιοελληνικός όρος ‘Ινδία’ απέκτησε τόση ασάφεια και γενίκευση όση κι ο όρος ‘Αιθιοπία’, ο οποίος περιέγραφε αρχικά το σημερινό Σουδάν (όχι την Αβησσυνία που σήμερα ψευδώς ονομάζεται Αιθιοπία). Οι δυο όροι τελικά αλληλο-επικαλύφθηκαν και ουσιαστικά κατάντησαν συνώνυμα του ‘Νότου’ κατά τους πρώτους χριστιανικούς αιώνες.

Όλα αυτά μας οδηγούν στο συμπέρασμα ότι σήμερα η χρήση της λέξης ‘Ινδίας’ — είτε για αναφορά στην Αρχαιότητα και στα Ισλαμικά Χρόνια, είτε για περιγραφή του συγχρόνου κράτους — είναι λαθεμένη και βεβαρυμένη με πολιτικές, αποικιοκρατικές κι οριενταλιστικές, σκοπιμότητες. Άλλωστε κι η περσική και ουρντού λέξη ‘Χιντουστάν’ σήμαινε και σημαίνει βασικά την περιοχή του Ινδού ποταμού, της Πενταποταμίας και ομόρων περιοχών.

Σχεδόν οι μισοί κάτοικοι του ψευτοκράτους ‘Ινδία’ είναι δραβιδικοί και δεν μιλούν ινδικά (χίντι). Η σημερινή Ινδία μπορεί να είναι μεγάλη αλλά αποτελεί κατ’ ουσίαν ένα νεο-αποικιακό ψευτοκράτος, όπως η Νιγηρία, η Αλγερία ή η Αίγυπτος, που δεν αποτελεί ‘έθνος’ αλλά απαρτίζεται από πολλά και διαφορετικά μεταξύ τους έθνη.

Κλείνω αυτή την αναφορά προσθέτοντας ότι η παραπάνω εθνοφυλετική και γεωγραφική διαφορά είναι ολότελα άσχετη από την θρησκευτική διαφορά Ισλάμ — ‘Ινδουϊσμού’ (μουσουλμάνων — ‘ινδουϊστών’), δεδομένου ότι μουσουλμάνοι υπάρχουν και ανάμεσα στους Ινδούς (: ‘ινδο-ευρωπαίους’) του Βορρά και ανάμεσα στους Δραβίδες του Ντεκάν, όπως είναι το όνομα του νότιου μισού της λεγόμενης ‘Ινδίας’.

Αν, τέλος, θέτω εντός εισαγωγικών τους όρους ‘Ινδουϊσμός’ και ‘ινδουϊστές’, αυτό οφείλεται στο γεγονός ότι είναι τόσο ψεύτικοι και λαθεμένοι όσο κι ο όρος ‘Ινδία’. Κατ’ ουσίαν δεν υπάρχει ‘ένας’ Ινδουϊσμός αλλά πολλοί (όπως κι η Χριστιανωσύνη δεν είναι μία, το Ισλάμ δεν είναι ένα, ο Βουδισμός δεν είναι ένας, κοκ). Κι επιπλέον υπάρχουν κι άλλες θρησκείες είτε στο Ντεκάν είτε στην βόρεια Ινδία. Γενικώτερα, στην ψευδή, αποικιοκρατική, οριενταλιστική Ιστορία της ‘Ινδίας’ θα επανέλθω με πολλά κείμενα.

Ό,τι ξέρει ο σημερινός κόσμος για την Ινδία είναι μια αγγλογαλλική παραχάραξη της Ιστορίας: για παράδειγμα, υπάρχουν αρχαιοελληνικά κείμενα του 1ου χριστιανικού αιώνα, όπως ο Περίπλους της Ερυθράς Θαλάσσης, που αναφέρουν τα πολλά και διαφορετικά κράτη, τα οποία βρίσκονταν τότε στον χώρο που στρεβλά σήμερα αποκαλούμε ‘Ινδία’, και όμως δεν τα αποκαλούν ‘ινδικά βασίλεια’, επειδή δεν ήταν ινδικά βασίλεια.

ΙΙ. Κοιλάδα του Ινδού, Πενταποταμία και Κοιλάδα του Γάγγη από τον Μεγάλο Αλέξανδρο στους Μεγάλους Μογγόλους Αυτοκράτορες

Μετά τον θάνατο του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου και μέχρι τα χρόνια της μογγολικής κατάκτησης της Κοιλάδας του Ινδού και της Κοιλάδας του Γάγγη, καμμιά ξένη δύναμη δεν κατέκτησε εκτάσεις που σήμερα ανήκουν στην χώρα που συμβατικά ονομάζεται Ινδία. Μόνον οι Ιρανοί Σασανίδες (Σασανιάν: 224–651) έφθασαν τα ανατολικά σύνορά τους τόσο μακριά όσο οι Αχαιμενιδείς κι ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος. Αλλά και εκείνοι σταμάτησαν εκεί.

Όταν οι Επίγονοι Σελευκιδείς και οι Πάρθες Αρσακιδείς (Ασκανιάν: η πιο μακραίωνη ιρανική δυναστεία — 250 π.Χ.-224 μ.Χ.) βρίσκονταν σε αδυναμία, πολλά αυτόνομα βασίλεια σχηματίζονταν από τα έθνη που κατοικούσαν στις ανατολικές επαρχίες τους, δηλαδή τον χώρο όπου σήμερα βρίσκονται το Πακιστάν, το Αφγανιστάν, το Ουζμπεκιστάν, το Τατζικιστάν, η Κιργιζία, οι ανατολικές εσχατιές του Ιράν και τα βορειοδυτικά άκρα της Ινδίας: η Σογδιανή, το ελληνιστικό κράτος της Βακτριανής, το ινδοπαρθικό κράτος, το ινδοσκυθικό κράτος, το κάποτε πανίσχυρο Κουσάν, οι Τόχαροι, και άλλα κεντρασιατικά τουρκόφωνα ή ινδοευρωπαϊκά κράτη.

Το τι αποκαλείται ‘αυτοκρατορία’ στην Αρχαία Ιστορία της ‘Ινδίας’, όπως την έχουν παρασκευάσει Άγγλοι, Γάλλοι, Ολλανδοί κι Αμερικανοί οριενταλιστές ‘Ινδολόγοι’, είναι βασικά μικρά κράτη (για τα μέτρα των Αχαιμενιδών, των Σελευκιδών και των Σασανιδών) που εκτείνονται κυρίως ανάμεσα στην Πενταποταμία και το Δέλτα του Γάγγη: το βασίλειο των Μαουρύα (322–185 π.Χ.) ή το βασίλειο των Γκούπτα (319–543 μ.Χ.). Αυτά ήταν όντως ινδικά — ινδοευρωπαϊκά βασίλεια. Όμως τα περισσότερα άλλα βασίλεια στα νότια δεν μπορούν να ονομασθούν ινδικά γιατί ήταν δραβιδικά. Και ήταν όλα πάντοτε μικρά τοπικά βασίλεια: όλη η Νότια Ασία ήταν κατά κανόνα πάντοτε κατακερματισμένη.

Οι πρώιμοι μουσουλμάνοι κι οι ισλαμικές στρατιές των μέσων του 7ου αιώνα που έφθασαν στο Πεντζάμπ και τα βορειοδυτικά άκρα της σημερινής Ινδίας ουσιαστικά επανέλαβαν την Ιστορία: εκμεταλλεύθηκαν κάτι το οποίο ‘είχαμε’ ξαναδεί! Όπως ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος, καταλύοντας το αχαιμενιδικό Ιράν, βρέθηκε σχεδόν ‘αυτόματα’ κυρίαρχος των ανατολικών σατραπειών κι εκτάσεών του, έτσι κι οι ισλαμικές στρατιές μετά τις μάχες στην Καντισίγια (636), Νεχαβέντ (642) και Μερβ (651) βρέθηκαν κυρίαρχοι των ανατολικών σατραπειών κι εκτάσεων του σασανιδικού Ιράν.

Ανάποδα, η Ιστορία επαναλήφθηκε και πάλι λίγους αιώνες αργότερα: στους χρόνους της αργής παρακμής και βαθμιαίας αποδυνάμωσης του αβασιδικού χαλιφάτου της Βαγδάτης. Ό,τι χαρακτήρισε τους Σελευκιδείς και τους Αρσακιδείς, συνέβη και τότε: πολλά μικρότερα ισλαμικά βασίλεια ξεφύτρωσαν κι αλληλοδιαδέχθηκαν το ένα το άλλο στην περιοχή ανάμεσα το κεντρικό ιρανικό οροπέδιο, την Αράλη στην Κεντρική Ασία και την Πενταποταμία.

Η μογγολική κατάκτηση της σημερινής βόρειας Ινδίας πιστοποιεί διαχρονικά ότι όλος ο χώρος ανάμεσα στο Δέλτα του Ινδού και στο Δέλτα του Γάγγη καταλαμβάνεται πιο εύκολα από τον βορρά παρά από τα δυτικά. Και δεν αναφέρομαι σε στρατιωτικές κατακτήσεις μόνον. Από τον 8ο αιώνα, με την διάδοση του Ισλάμ στην Κεντρική Ασία, πολλά τοπικά τουρκόφωνα φύλα αποψιλώνονταν από τους πιο ικανούς πολεμιστές τους, οι οποίοι έβλεπαν ότι, αν αποδέχονταν το Ισλάμ, θα μπορούσαν να έχουν μια πολύ επιτυχημένη σταδιοδρομία ως στρατιωτικοί σε μια τεράστια αυτοκρατορία.

Έτσι, πολλοί ευχαρίστως προσέρχονταν για να προσλήφθούν ως δούλοι-πολεμιστές. Στο αβασιδικό χαλιφάτο υπήρχαν ήδη πολυάιθμοι και για όλους τους εχρησιμοποιείτο η αραβική λέξη ‘ιδιοκτησία’, διότι ως σκλάβοι αποτελούσαν την ιδιοκτησία (‘μαμλούκ’ / πληθυντικός: μαμαλίκ) των κυρίων τους. Αυτοί είναι οι Μαμελούκοι.

Μαμελούκοι υπήρχαν παντού: στην Κεντρική Ασία, στην Πενταποταμία, στις κεντρικές περιοχές του χαλιφάτου, στην Αίγυπτο, και στην βορειοδυτική Αφρική. Η κατά τόπους ιστορία τους είναι απλή: πρώτα ήταν σκλάβοι-πολεμιστές, έπειτα απελεύθεροι, ύστερα παράκλητοι ως εμπειροπόλεμοι, και τελικά κυρίαρχοι ηγεμόνες.

Αλλά δεν υπήρχε πουθενά ένας εθνικού χαρακτήρα συντονισμός. Και δεν μπορούσε να υπάρχει, επειδή οι ‘μαμελούκοι’ ανήκαν σε διαφορετικές τουρκόφωνες φυλές, μιλούσαν σχετικά διαφορετικές γλώσσες, κι ενθυμούνταν τις πάντοτε υπαρκτές ενδοτουρκικές εχθρότητες κι αντιπαλότητες. Όποιοι πετύχαιναν σε ένα κάποιο τόπο κυριαρχούσαν εκεί. Δεν υπήρχε δυναστεία Μαμελούκων μόνον στην Αίγυπτο, όπως είναι περισσότερο γνωστό στην Ελλάδα.

Υπήρχαν πολλές κατά τόπους δυναστείες Μαμελούκων που όλοι τους ήταν τουρκόφωνοι — αν κι αυτό δεν σημαίνει την ίδια γλώσσα, εφόσον άλλα τα Κιπτσάκ, άλλα τα Τσαγατάι, άλλα τα τουρκμενικά, άλλα τα των Ογούζων (ή Ούζων — Ουζμπέκων), κοκ.

Αλλά τα φαρσί ήταν πάντοτε η γλώσσα της λογοτεχνίας και της ιστορίας και τα αραβικά η γλώσσα της επιστήμης και της θρησκείας.

Μετά την πρώιμη ισλαμική επέλαση μέχρι την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού και την Πενταποταμία, η διάδοση του Ισλάμ στην Νότια Ασία (βόρεια Ινδία: ανάμεσα στο Δέλτα του Ινδού και στο Δέλτα του Γάγγη / Ντεκάν: το κατοικούμενο από μη Ινδούς, Δραβίδες, νότιο ήμισυ της σημερινής Ινδίας) δεν ήταν ποτέ θέμα του Ισλαμικού Χαλιφάτου της Δαμασκού (661–750) και της Βαγδάτης (750–1258), όπως συχνά σήμερα Ινδουϊστές εθνικιστές εσφαλμένα ισχυρίζονται.

Αντίθετα, ήταν υπόθεση πολέμου ανάμεσα σε ινδικά ινδουϊστικά βασίλεια της Κοιλάδας του Γάγγη και σε μικρότερα ισλαμικά βασίλεια που ξεφύτρωσαν κι αλληλοδιαδέχθηκαν το ένα το άλλο στην περιοχή ανάμεσα το κεντρικό ιρανικό οροπέδιο, την Αράλη στην Κεντρική Ασία και την Πενταποταμία, όπως προανέφερα, εξαιτίας της βαθμιαίας αποδυνάμωσης του αβασιδικού χαλιφάτου της Βαγδάτης.

Αυτά τα ισλαμικά βασίλεια, όπως οι Γαζνεβίδες (977–1186 / το Γαζνί βρίσκεται στο σημερινό Αφγανιστάν), είτε διέθεταν Μαμελούκους είτε είχαν συσταθεί από Μαμελούκους.

Οι πόλεμοι αυτών των βασιλείων με τα ινδικά ινδουϊστικά βασίλεια απέληξαν στην διάδοση του Ισλάμ στον ευρύτερο χώρο της Νότιας Ασίας.

Έτσι, αυτό που αποκαλούμε ‘Σουλτανάτο του Δελχί’, ουσιαστικά αποτελεί μια διαδοχή πέντε διαφορετικών δυναστειών που προέρχονται από Μαμελούκους, δηλαδή διάφορα τουρκόφωνα αλλά και άλλα κεντρασιατικά φύλα.

Αυτές οι πέντε ισλαμικές δυναστείες με βάση το Δελχί (: το Παλαιό Δελχί) διεξήγαγαν πολέμους με τα ινδικά και τα δραβιδικά βασίλεια είτε του χώρου ανάμεσα στο Δέλτα του Ινδού και στο Δέλτα του Γάγγη είτε του Ντεκάν.

Οι πέντε δυναστείες καλύπτουν ένα διάστημα άνω των τριών αιώνων: Μαμελούκοι (1206–1290), Χάλτζι (Khalji: 1290–1320), Τούγλακ (Tughlaq: 1320–1414), Σαγίντ (Sayyid: 1414–51), και Λόντι (Lodi: 1451–1526).

Αυτοί μάλιστα ήταν ικανοί να σταθούν με επιτυχία απέναντι στον Χουλάγκου και να αποκρούσουν τις πρώτες μογγολικές επελάσεις (1221–1327), ενώ η Βαγδάτη κατέρρευσε το 1258.

Τότε διαμορφώθηκε μια κοσμοπολίτικη και πολύ ανεκτική κοινωνική κατάσταση που προσέλκυσε Ιρανούς, Κεντρασιάτες, Τουρκόφωνους και Μογγόλους που ελάχιστη σημασία απέδιδαν σε θρησκευτικές διαφορές — σιίτες ή σουνίτες, μουσουλμάνους, χριστιανούς (Νεστοριανούς), μανιχεϊστές, βουδιστές ή ινδουϊστές.

Η εθνοφυλετική σύνθεση των Ινδο-Ευρωπαίων Ινδών του χώρου της σημερινής βόρειας Ινδίας άλλαξε ολότελα και δημιουργήθηκε ένα τουρκο-μογγολο-κεντρασιατο-ιρανο-ινδικό εθνογλωσσικό μείγμα, το οποίο φτάνει μέχρι τις μέρες μας: η επίσημη γλώσσα του Πακιστάν (ουρντού) είναι μια τουρκική λέξη (ordu) που σημαίνει ‘στρατός’.

Αυτή είναι μια μεικτή τουρκική (Turkic), περσική, αραβική κι ινδική γλώσσα, στην οποία το ινδικό λεξιλόγιο (που προέρχεται από αρχαίες ινδικές — ινδο-ευρωπαϊκές γλώσσες όπως τα σανσκριτικά και τα πρακριτικά) είναι σχετικά μικρό.

Η ίδια γλώσσα είναι επίσημη και στην Ινδία, πλην όμως εκεί λέγεται χίντι, γράφεται σε Ντεβαναγκάρι σύστημα (οφειλόμενο σε αρχαία Μπραχμί γραφή) και όχι σε φαρσί (όπως τα ουρντού που έχουν μερικά επιπλέον γράμματα για φθόγγους ανύπαρκτους στα φαρσί), και απλώς δεν έχει τους ισλαμικούς όρους που έχει κάθε γλώσσα μουσουλμάνων. Αλλά κατ’ ουσίαν ουρντού και χίντι είναι μία γλώσσα και με εκτεταμένο τουρκικό (Turkic) λεξιλόγιο.

Αν το Σουλτανάτο του Δελχί γλύτωσε από τον Τσενγκίζ Χαν, δεν απέφυγε τον Ταμερλάνο. Το 1398 ο στρατός του Τιμούρ Λενγκ κατέλαβε το Δελχί κι επακολούθησε μια απερίγραπτη λεηλασία και σφαγή. Η πόλη εκθεμελιώθηκε. Στην συνέχεια αναθεμελιώθηκε και το Σουλτανάτο συνεχίστηκε αν και ιδιαίτερα αποδυναμωμένο.

Το τέλος της τελευταίας δυναστείας του Δελχί δόθηκε από τον Μπαμπούρ (στα περσικά σημαίνει ‘Τίγρης’) απόγονο του Ταμερλάνου, ο οποίος ήταν γιος του κυβερνήτη της Φεργάνα του Τουρκεστάν (σήμερα στο ανατολικό Ουζμπεκιστάν).

Μετά από πολλές πολεμικές κατακτήσεις στην Κεντρική Ασία, στράφηκε στην Ινδία και μετά από τη νίκη στην μάχη του Πανιπάτ θεμελίωσε το 1526 την δυναστεία που αποκαλείται Μουγάλ (Mughal) στην διεθνή βιβλιογραφία.

Ουσιαστικά, ο όρος Μογγόλος σήμαινε στρατιωτική βαθμίδα στα Τσαγατάι τουρκικά, την σήμερα νεκρή πλέον γλώσσα του Ταμερλάνου. Το πραγματικό όνομα, με το οποίο οι ίδιοι οι Μεγάλοι Μογγόλοι αυτοκράτορες (‘σάχηδες’) αποκαλούσαν τους εαυτούς τους και το κράτος τους, ήταν η περσική λέξη Γκουρκανιάν που (στον πληθυντικό) σημαίνει ‘Γαμπροί’.

Ο όρος κατάγεται από πολεμικές — βασιλικές πρακτικές τουρκόφωνων φύλων από τα χρόνια του Τσενγκίζ Χαν (και ίσως και πιο πριν, αλλά τουλάχιστον τότε έγινε γνωστός στους Ιρανούς κι άρχισαν να τον χρησιμοποιούν).

Κατ’ αυτές τις πρακτικές, ένας πολύ γενναίος στρατιώτης — πολεμιστής από μια μάλλον κατώτερη τουρκόφωνη φυλή, αφού επιδείξει ανδρεία σε μια ή περισσότερες μάχες, ζητάει να παντρευτεί την κόρη ενός στρατιωτικού ηγέτη από μια άλλη, ανώτερη τουρκόφωνη φυλή, κι αφού αυτό γίνει, αποκτάει ο ίδιος μεγαλύτερη σημασία και κοινωνική, δηλαδή στρατιωτική, υπόσταση.

Μετά τον Μπαμπούρ (1504–1530), οι Γκορκανιάν κυριάρχησαν σε όλες τις εκτάσεις ανάμεσα στο Δέλτα του Ινδού και το Δέλτα του Γάγγη, επέκτάθηκαν τόσο προς Αφγανιστάν και Κεντρική Ασία (από όπου κατάγονταν) όσο και προς τα νότια στο Ντεκάν, κι αναγνωρίστηκαν ως σύμμαχοι από τους Ιρανούς Σαφεβίδες που δεν ήταν Πέρσες αλλά Τουρκμένοι.

Και έτσι δημιουργήθηκε μια εκπληκτική τουρκόφωνη κυριαρχία από την Αλγερία και την Δυτική Μεσόγειο μέχρι την Μυανμάρ, Ταϋλάνδη και την Κίνα, κατά την οποία τρεις τουρκόφωνοι μουσουλμάνοι αυτοκράτορες, ένας Οθωμανός, ένας Σαφεβίδης κι ένα Γκουρκανί, έλεγχαν το μεγαλύτερο τμήμα του τότε γνωστού κόσμου.

Η κοινή καταγωγή και η κοινή θρησκεία δεν εξασφάλισαν ωστόσο καμμία ενότητα.

Οι Σαφεβίδες θεμελίωσαν το πρώτο σιιτικό κράτος στην Παγκόσμια Ιστορία και κατασφάζονταν ασταμάτητα με τους σουνίτες Οθωμανούς από την σημερινή νότια Ρωσσία μέχρι το Ομάν, ενώ οι επίσης σουνίτες Μεγάλοι Μογγόλοι Γκουρκανιάν παρέμειναν ως επί το πλείστον ουδέτεροι.

Σάχης Ταχμάσπ Α’ του Ιράν, στα αριστερά, και Σάχης Χουμαγιούν των Γκορκανιάν (Μεγάλη Μογγολική Αυτοκρατορία της ‘Ινδίας’), στα δεξιά

Μάλιστα μερικές φορές οι Γκουρκανιάν είχαν και καλές σχέσεις με τους Σαφεβίδες, όπως τεκμηριώνει η επίσκεψη (1544) του Χουμαγιούν (γιου του Μπαμπούρ) στο Εσφαχάν του Ιράν και οι απίστευτες ευωχίες και συμπόσια που έλαβαν χώραν εκεί με τον Σάχη Ταχμάσπ Α’ (1524–1576), ο οποίος βοήθησε τον Μεγάλο Μογγόλο να εξαφανίσει την απειλή που ήταν για τον θρόνο του ο Σερ Σάχης Σουρί (Sher Shah Suri), ένας Παστούνος που είχε στήσει μια εξουσία στην Βεγγάλη.

Οι Μεγάλοι Μογγόλοι συσσώρευσαν τεράστιο πλούτο, τον οποίο όμως δεν χρησιμοποίησαν για κάτι το συγκεκριμένο. Μετά τον Αουράνγκζεμπ (1658–1707) άρχισε η παρακμή. Η κατάσταση στο Ιράν ήταν παράλληλη: το 1736 η σαφεβιδική δυναστεία έπαιρνε ένα τέλος.

Ήταν η ώρα για τον Δεύτερο Μεγαλέξανδρο, όπως τον αποκαλούσαν οι σύγχρονοί του Ιρανοί, Κεντρασιάτες, Οθωμανοί κι άλλοι ή τον Ναπολέοντα της Ασίας, όπως τον επονόμαζαν αργότερα Ευρωπαίοι συγγραφείς: τον Ναντέρ Σάχη. Γνωρίζουμε ότι στην εξορία του ο Ναπολέων διάβαζε συγγράμματα Ευρωπαίων που αναφέρονταν στους πολέμους και στις τακτικές του Ναντέρ Σάχη.

ΙΙΙ. Ο Ναντέρ Σάχης (1736–1747) κι η Κατάληψη του Δελχίου (1739)

Ο Ναντέρ Σάχης ήταν μια από τις πάμπολλες περιπτώσεις που πιστοποιούν την υπεροχή των γεωργών προ όλων των άλλων τομέων ανθρώπινης εργασίας και δραστηριότητας.

Μια από τις αναρίθμητες περιπτώσεις που βεβαιώνουν ότι οι άνθρωποι των πόλεων είναι καθοριστικά κι απόλυτα κατώτεροι από τους ανθρώπους που δουλεύουν την γη. Γεννήθηκε σε μια μικρή πόλη του Χορασάν (σήμερα ΒΑ Ιράν) σε μια φτωχή οικογένεια Τουρκμένων αγροτών της φυλής Αφσάρ (افشار / Afshar). Το όνομα αυτό απαντάται σήμερα ακόμη ως επώνυμο σχεδόν σε όλα τα μήκη και πλάτη του μουσουλμανικού κόσμου, ιδιαίτερα βέβαια από την Τουρκία μέχρι την Κίνα.

Αφού πέρασε μια παιδική και νεανική ζωή με πολλές δοκιμασίες (έχασε τον πατέρα του, αιχμαλωτίσθηκε με την μητέρα του, κλπ) κι αφού έγινε Κιζιλμπάσης (‘Ερυθρίνος’), συνέχισε να ζει μια απλή ζωή στρατιώτη μέχρι τα 30 του. Είχε έτσι πάρει ένα πολύ σπάνιο μάθημα από την ζωή, το μόνο απαραίτητο για να γίνει κάποιος άνθρωπος ένας πραγματικά κορυφαίος αυτοκράτορας: περιφρονούσε τα πλούτη, τα αξιώματα, την χλιδή και την πολυτέλεια των ανακτόρων. Ζούσε στα τελευταία σαφεβιδικά χρόνια.

Η αδύναμη εξουσία των τελευταίων σάχηδων του Εσφαχάν ήταν αιτία απόσχισης τοπικών κυβερνητών (στο Αφγανιστάν), ρωσσικών κατακτήσεων στον Καύκασο, οθωμανικής επιθετικότητας και γενικευμένου χάους από την απόπειρα των Αφγανών επαναστατών υπό τον Μαχμούντ Χοτακί να ανατρέψει τον Σουλτάν Χουσεΰν, τελευταίο Σαφεβίδη.

Από το 1722 μέχρι το 1736 (δηλαδή σε ηλικία 34–48 ετών), ο Ναντέρ πολέμησε σε πολλές μάχες για να καταστείλει την αφγανική εξέγερση, να εκδιώξει τους επαναστάτες από την πρωτεύουσα Εσφαχάν και να την αποδώσει στον νόμιμο σάχη Ταχμάσπ Β’, πριν οριστεί διοικητής των ανατολικών επαρχιών και συνενώσει όλες τις ανατολικές επαρχίες της χώρας.

Επίσης πολέμησε ενάντια στους Οθωμανούς, έσπευσε στο Αφγανιστάν για να καταστείλει νέα εξέγερση, υποχρέωσε τον Ταχμάσπ Β’ να παραιτηθεί, όταν ο ανήμπορος σάχης από ζήλεια είχε επιχειρήσει μόνος του μια αποτυχημένη εκστρατεία στον Καύκασο, κι ορίστηκε αντιβασιλέας του γιου του Ταχμάσπ Β’ Αμπάς Γ’.

Μετά από μια σειρά σημαντικών μαχών και νικών κατά των Οθωμανών στον Καύκασο και μετά την εκ μέρους του κατάληψη της Βαγδάτης, υποχρέωσε τους Οθωμανούς να παραχωρήσουν τα ιρανικά εδάφη που είχαν παλαιότερα κατακτήσει στον Καύκασο (Γεωργία και Αρμενία). Και στις 8 Μαρτίου 1736 στέφθηκε σάχης από μια γενική συνέλευση στρατιωτικών, ευγενών και κληρικών που καταλάβαιναν ότι ο μικρός Αμπάς Γ’ ήταν ανίκανος να βασιλεύσει.

Η εκπληκτική ικανότητα του Ναντέρ να ηγείται αριθμητικά μικρότερων στρατευμάτων και να σημειώνει σημαντικές νίκες εναντίον εχθρών — με υπέρτερες δυνάμεις χάρη σε εντυπωσιακούς αιφνιδιασμούς και τεχνικές, απατηλές κινήσεις και πλευροκοπήματα — χαρακτήρισε την περίοδο των έντεκα ετών κατά την οποία βασίλευσε. Σε μια εποχή χωρίς τανκς και μηχανοκίνητες μονάδες, στρατεύματα μετακινούνταν με εκπληκτικές ταχύτητες μέσα από πολύ δύσβατες και δυσπρόσιτες περιοχές, από τον Καύκασο στον Ινδό, από την Κεντρική Ασία στη Μεσοποταμία, κι από το Αφγανιστάν στον Περσικό Κόλπο.

Ο Ναντέρ Σάχης γεννήθηκε σε μια σιιτική οικογένεια αλλά σε μεγαλύτερη ηλικία έδειξε συμπάθεια προς το σουνιτικό Ισλάμ και προσπάθησε να οργανώσει μια σύνθεση και συνένωση των δύο θεολογιών.

Ως άτομο ήταν ίσως ο πιο ανεξίθρησκος ηγεμόνας του Ιράν και η φιλία του προς χριστιανικούς πληθυσμούς ήταν τέτοια που συμπεριέλαβε συχνά Γεωργιανούς κι Αρμένιους στο στράτευμά του.

Θα μπορούσε κανείς εύκολα να τον περιγράψει και ως ένα Κεμάλ Ατατούρκ πριν τον Κεμάλ Ατατούρκ, επειδή καμμιά στρατιωτική του επιχείρηση δεν είχε θρησκευτικά κίνητρα ή σκοπιμότητες.

Όπου έκρινε κι αποφάσιζε ο Ναντέρ Σάχης, η θρησκεία δεν είχε θέση κι όλοι οι άνθρωποι ήταν ίσοι και κρίνονταν με βάση τις ικανότητές τους.

Οι σιίτες μολάδες κι αγιατολάδες κι ο σεϊχουλισλάμης της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας είχαν βρει τον μπελά τους μαζί του.

Η κατάκτηση του Δελχί κι η εκτεταμένη λαφυραγώγηση του πλουσιώτατου γείτονα του Ιράν δεν έγιναν ούτε με σκοπό το κέρδος ούτε για να προσπορισθεί ο Ναντέρ Σάχης φήμη και δόξα.

Απλώς του χρειάζονταν έσοδα για τους πολέμους κατά των Οθωμανών που προετοίμαζε στο μυαλό του.

Ο ετήσιος προϋπολογισμός του κράτους του Αουράνγκζεμπ μόλις 25 χρόνια πριν καταλάβει το Δελχί ο Ναντέρ Σάχης ήταν δεκαπλάσιος εκείνου της Γαλλίας του Λουδοβίκου ΙΔ’ (‘βασιλιά ήλιου’)!

Η στρατιωτική τεχνική του Ναντέρ Σάχη στην μάχη του Καρνάλ (13 Φλεβάρη 1739) ήταν εκπληκτική.

Και η λαφυραγώγηση των ανακτόρων των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων στο Δελχί ξεπερνάει κάθε ιστορική αναφορά και κάθε τρελή φαντασία.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — –

Οι Ατελείωτες Μάχες του Ναντέρ Σάχη

Πρώτη εκστρατεία στο Αφγανιστάν — 1729

Η Μάχη στο Μαλαγιέρ, στην οροσειρά του Κεντρικού Ζάγρου, κατά των Οθωμανών — 1730

Η Μάχη στο Μπαγκαβάρντ του Καυκάσου κατά των Οθωμανών — 1735

Μάχη στα Στενά Χάυμπερ, στα βουνά μεταξύ των σημερινών Πακιστάν κι Αφγανιστάν, στην πορεία για κατάληψη του Δελχί — 1738. Πολέμησαν 10000 Ιρανοί υπό τον Ναντέρ Σάχη και νίκησαν 70000 στρατιώτες της Μογγολικής Αυτοκρατορίας των Γκορκανιάν της ‘Ινδίας’.

Η μάχη του Καρνάλ όπου ο Ναντέρ Σάχης πολέμησε εναντίον εξαπλασίων στρατευμάτων (55000 κατά 300000) και νικώντας τα εβάδισε εναντίον του Δελχί — 1739. Οι αντίπαλοι υποστηρίζονταν από 2000 εκπαιδευμένους για πόλεμο ελέφαντες και 3000 κανόνια.

Η μάχη του Καρς: 80000 Ιρανοί κατά 140000 Οθωμανών — 1745. Ιρανική νίκη με νεκρούς και τραυματισμένους 8000 Ιρανούς και Οθωμανούς 12000 νεκρούς, 18000 τραυματισμένους και 5000 αιχμαλώτους

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Κι όμως ο συνεχώς μάχιμος αυτός γεωργός — στρατιώτης — σάχης δεν θεώρησε αυτή την ιστορική νίκη γεγονός άξιο για να πανηγυρίσει κι αμέσως στράφηκε σε άλλους πολέμους.

Επιστρέφοντας όμως από το Δελχί πήρε τους στρατηγούς του (που ήταν όλοι τους Ιρανοί ευγενείς) και τους οδήγησε στο μικρό χωριό του Χορασάν όπου είχε γεννηθεί. Εκεί τους είπε:

– Βλέπετε σε τι ύψη εξυψώνει ο Μεγαλοδύναμος αυτούς που επιλέγει; Γι’ αυτό, ποτέ μην περιφρονείτε ένα άνθρωπο με ταπεινή καταγωγή και με ελάχιστη περιουσία!

Μετά από άλλα οκτώ χρόνια γεμάτα πολέμους κατά της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας στην αραβική χερσόνησο, την Μεσοποταμία και τον Καύκασο, μετά από εκστρατείες στην Κεντρική Ασία και στα παράλια του Ομάν, ο Ναντέρ Σάχης είχε το τέλος που οι ήρωες αντιμετωπίζουν στα χέρια δειλών συνωμοτών (εκτός κι αν συνωμοσίες δεν υπάρχουν!).

Δολοφονήθηκε όταν κοιμόταν από δέκα πέντε συνωμότες την 20 η Ιουνίου 1747.

Στην συνέχεια θα βρείτε μια σειρά από διαφωτιστικές δημοσιεύσεις σχετικά με την ζωή, το έργο, τις στρατιωτικές κατακτήσεις και την κοσμοαντίληψη του πιο τρομερού Ιρανού της δεύτερης χιλιετίας.

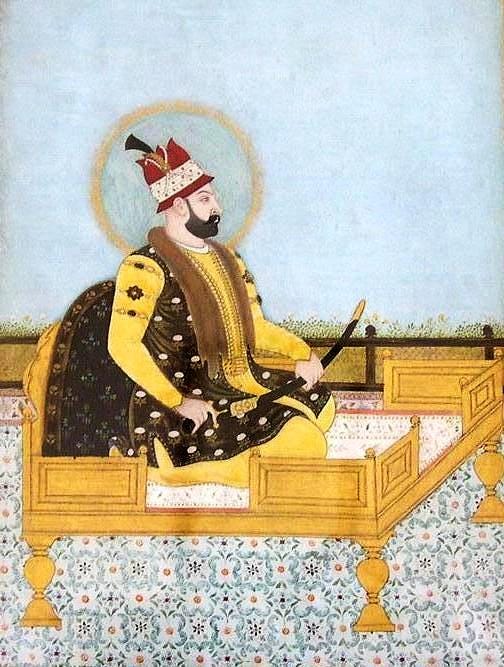

Ο Σάχης Ναντέρ κάθεται στον Θρόνο του Παγωνιού, τον μυθικής αξίας χρυσοποίκιλτο κι εμβληματικό θρόνο των Μεγάλων Μογγόλων Αυτοκρατόρων Γκορκανιάν του Δελχί τον οποίο λαφυραγώγησε μαζί πολλά άλλα αμύθητα πλούτη και πετράδια.

Αποσπάσματα από Ιστορικά Κείμενα-Quotes

Afterwards Nadir Shah himself, with the Emperor of Hindustan, entered the fort of Delhi. It is said that he appointed a place on one side in the fort for the residence of Muhammad Shah and his dependents, and on the other side he chose the Diwan-i Khas, or, as some say, the Garden of Hayat Bakhsh, for his own accommodation. He sent to the Emperor of Hindustan, as to a prisoner, some food and wine from his own table.

One Friday his own name was read in the khutba, but on the next he ordered Muhammad Shah’s name to be read. It is related that one day a rumour spread in the city that Nadir Shah had been slain in the fort. This produced a general confusion, and the people of the city destroyed five thousand men of his camp. On hearing of this, Nadir Shah came of the fort, sat in the golden masjid which was built by Rashanu-d daula, and gave orders for a general massacre.

For nine hours an indiscriminate slaughter of all and of every degree was committed. It is said that the number of those who were slain amounted to one hundred thousand. The losses and calamities of the people of Delhi were exceedingly great….

After this violence and cruelty, Nadir Shah collected immense riches, which he began to send to his country laden on elephants and camels.

Tarikh-i Hindi

by Rustam ‘Ali

In: The History of India as Told by its own Historians

The Posthumous Papers of the Late Sir H. M. Elliot

John Dowson, ed. 1st ed. 1867. 2nd ed., Calcutta: Susil Gupta, 1956, vol. 22, pp. 37–67

When the Shah departed towards the close of the day, a false rumour was spread through the town that he had been severely wounded by a shot from a matchlock, and thus were sown the seeds from which murder and rapine were to spring. The bad characters within the town collected in great bodies, and, without distinction, commenced the work of plunder and destruction….

On the morning of the 11th an order went forth from the Persian Emperor for the slaughter of the inhabitants. The result may be imagined; one moment seemed to have sufficed for universal destruction. The Chandni chauk, the fruit market, the Daribah bazaar, and the buildings around the Masjid-i Jama’ were set fire to and reduced to ashes.

The inhabitants, one and all, were slaughtered. Here and there some opposition was offered, but in most places people were butchered unresistingly. The Persians laid violent hands on everything and everybody; cloth, jewels, dishes of gold and silver, were acceptable spoil….

But to return to the miserable inhabitants. The massacre lasted half the day, when the Persian Emperor ordered Haji Fulad Khan, the kotwal, to proceed through the streets accompanied by a body of Persian nasakchis, and proclaim an order for the soldiers to resist from carnage. By degrees the violence of the flames subsided, but the bloodshed, the devastation, and the ruin of families were irreparable. For a long time the streets remained strewn with corpses, as the walks of a garden with dead flowers and leaves.

The town was reduced to ashes, and had the appearance of a plain consumed with fire. All the regal jewels and property and the contents of the treasury were seized by the Persian conqueror in the citadel. He thus became possessed of treasure to the amount of sixty lacs of rupees and several thousand ashraf is… plate of gold to the value of one kror of rupees, and the jewels, many of which were unrivalled in beauty by any in the world, were valued at about fifty krors.

The peacock throne alone, constructed at great pains in the reign of Shah Jahan, had cost one kror of rupees. Elephants, horses, and precious stuffs, whatever pleased .the conqueror’s eye, more indeed than can be enumerated, became his spoil. In short, the accumulated wealth of 348 years changed masters in a moment.

About Shah’s sack of Delhi

Tazrikha by Anand Ram Mukhlis

A history of Nâdir Shah’s invasion of India

In The History of India as Told by its own Historians

The Posthumous Papers of the Late Sir H. M. Elliot.

John Dowson, ed. 1st ed. 1867. 2nd ed., Calcutta: Susil Gupta, 1956, vol. 22, pp. 74–98.

Ανδριάντας του Ναντέρ Σάχη σήμερα στο Ιράν

Nāder Shah

Nāder Shah, ruler of Iran, 1736–47. He rose from obscurity to control an empire that briefly stretched across Iran, northern India, and parts of Central Asia. He developed a reputation as a skilled military commander and succeeded in battle against numerous opponents, including the Ottomans and the Mughals.

During Nāder’s campaign in India, and several years after he had replaced the last Safavid ruler on the Persian throne, the elimination of much of the Safavid family effectively ended any real possibility of a Safavid restoration. The decade of Nāder’s own tumultuous reign was marked by conflict, chaos, and oppressive rule. Nāder’s troops assassinated him in 1747, after he had come to be regarded as a cruel and capricious tyrant. His empire quickly collapsed, and the resulting fragmentation of Iran into several separate domains lasted until the rise of the Qajars decades later.

Born in November 1688 into a humble pastoral family, then at its winter camp in Darra Gaz in the mountains north of Mashad, Nāder belonged to a group of the Qirqlu branch of the Afšār Turkmen. Beginning in the 16th century, the Safavids had settled groups of Afšārs in northern Khorasan to defend Mashad against Uzbek incursions.

The first major international political event that directly affected Nāder’s career was the Afghan invasion of Iran in the summer of 1719 that resulted in the capture of Isfahan and deposition of Shah Solṭān Ḥosayn, the last Safavid monarch, by the autumn of 1722. After the fall of Isfahan, Safavid pretenders emerged all over Iran. One was Solṭān Ḥosayn’s son Ṭahmāsb, who escaped to Qazvin, where he was proclaimed Shah Ṭahmāsb II.

He led a resistance movement against the Afghans during the 1720s. The Russians and Ottomans saw the Afghan conquest as their own opportunity to acquire territory in Iran, so both invaded and occupied some land in 1723. The following year they signed a treaty in which they recognized each other’s territorial gains and agreed to support the restoration of Safavid rule.

Around this time, Nāder began his career in Abivard, an Afšār-controlled town just north of Mashad. He made himself so useful to the local ruler Bābā ʿAli Beg that he gave Nāder two of his daughters in marriage. Due to internal tribal rivalries, Nāder was not able to become Bābā ʿAli’s successor, so he vied for power with various upstart military chiefs in northeastern Iran who had emerged in the wake of the Afghan invasion.

In the mid 1720s, Nāder played an important role in defeating Malek Maḥmud Sistāni, one of that area’s main warlords, who had set himself up as the scion of the 9th-10th century Saffarid dynasty. Nāder was his ally for a while but soon turned against him. His role in suppressing this usurper brought him to Ṭahmāsb’s attention. Ṭahmāsb chose him as his principal military commander to replace Fatḥ ʿAli Khan Qajar (d. 1726), whose descendants (the founders of the Qajar dynasty) blamed Nāder for the murder of their ancestor.

With this promotion, Nāder assumed the title Ṭahmāsb-qoli (servant of Ṭahmāsb). His prestige steadily increased as he led Ṭahmāsb’s armies to numerous victories. He first defeated the Abdāli (later known as Dorrāni) Afghans near Herat in May 1729, then achieved victory over the Ḡilzi Afghans led by Ašraf at Mehmāndust on 29 September 1729.

After this battle, when Ašraf fled from Isfahan to Qandahar, Ṭahmāsb became finally established in Isfahan (with Nāder in actual control of affairs) by December 1729, marking the real end of Afghan rule in Iran. In the wake of Ašraf’s defeat, many Afghan soldiers joined Nāder’s army and proved helpful in many subsequent battles.

Three months before the Mehmāndust victory, Nāder had sent letters to the Ottoman Sultan Aḥmad III (r. 1703–30) to ask for help, since Ṭahmāsb “was made the legitimate successor of his esteemed father [Solṭān Ḥosayn]” (Nāṣeri, p. 210). Receiving no response, Nāder attacked the Ottomans as soon as Ašraf was defeated and Isfahan reoccupied. He waged a successful campaign during the spring and summer of 1730 and recaptured much territory that the Ottomans had taken in the previous decade.

But, just as the momentum of his offensive was building, news came from Mashad that the Abdāli Afghans had attacked Nāder’s brother Ebrāhim there and pinned him down inside the city’s walls. Nāder rushed to relieve him. (This distraction came at just the right time for the Ottomans, since in Istanbul the Patrona Halil rebellion, which led to the deposition of Aḥmad III, broke out in September 1730). Nāder arrived in Mashad in time to attend the wedding of his son Reżā-qoli to Ṭahmāsb’s sister Fāṭema Solṭān Begum.

Nāder spent the next fourteen months subduing Abdāli forces led by Allāh-Yār Khan. To commemorate his victory over them, he endowed in Mashad a waqf (pious foundation) at the shrine of Imam ʿAli al-Reżā (d. ca. 818). Nāder’s personal seal, preserved on the waqf deed of June 1732, showed his unremarkable Shiʿite loyalty at that time: Lā fatā illā ʿAli lā sayf illā Ḏu’l-Faqār / Nāder-e ʿaṣr-am ze loṭf-e Ḥaqq ḡolām-e hašt o čār (There is no youth more chivalrous than ʿAli, no sword except Ḏu’l-Faqār / I am the rarity of the age, and by the grace of God, the servant of the Eight and Four [i.e., the Twelve Imams].” (Šaʿbāni, p. 375; cf. Rabino, p. 53).

Ṭahmāsb took Nāder’s absence in Khorasan as his own chance to attack the Ottomans and pursued a disastrous campaign (January 1731–January 1732), in which the Ottomans actually reoccupied much of the territory recently lost to Nāder. Sultan Maḥmud I (r. 1730–54) negotiated with Ṭahmāsb a peace agreement that allowed the Ottomans to retain these lands, while returning Tabriz to avoid angering Nāder.

Three weeks later, Russia and Persia signed the Treaty of Rašt, in which Russia, trying to curry favor with Persia against the Ottomans, agreed to withdraw from most of the Iranian territory it had annexed in the 1720s.

When Nāder learned that Ṭahmāsb had relinquished substantial territory to the Ottomans, he quickly returned to Isfahan. He used the peace treaty as an excuse to remove Ṭahmāsb from the throne in August 1732 and replace him with Ṭahmāsb’s eight-month-old son, who was given the regnal name ʿAbbās III. Now regent, Nāder resumed hostilities against the Ottomans.

After a decisive round of victories, interspersed with short excursions to quell uprisings in Fārs and Baluchistan, he signed a new treaty in December 1733 with Aḥmad Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Baghdad. It marked an attempt to reinstate the provisions of the 1049/1639 Ottoman-Safavid Treaty of Qaṣr-e Širin (Ḏohāb), since it called for the restoration of the borders stipulated at that time, a prisoner exchange, and Ottoman protection for all Persian ḥajj pilgrims. The Ottoman sultan would not ratify it, because disputes persisted over control of parts of the Caucasus, and so intermittent hostilities continued.

In March 1734, Šāhroḵ was born to Reżā-qoli and Fāṭema Begum. Šāhroḵ thus formed a direct link between the lineages of Nāder and the Safavids — an important basis for Šāhroḵ’s eventual right to rule. The choice to name his grandson after Šāhroḵ b. Timur (r. 1409–47) revealed Nāder’s growing interest in emulating the conqueror Timur (r. 1369–1405).

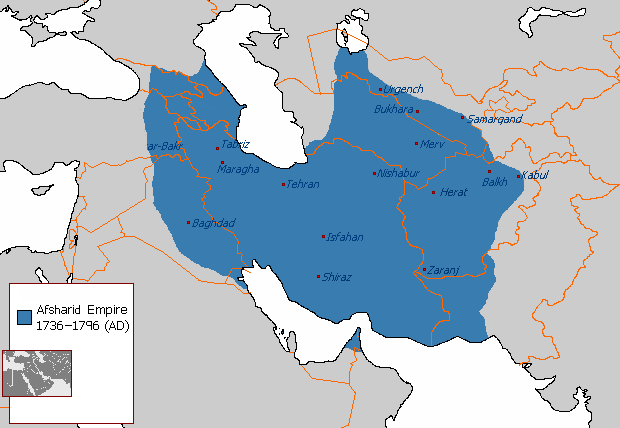

Το Ιράν στα χρόνια του Ναντέρ Σάχη

There followed another series of Ottoman-Persian battles in the Caucasus, and Nāder’s capture of Ganja, during the siege of which Russian engineers provided assistance. Russia and Persia then signed a defensive alliance in March 1735 at Ganja. In the treaty, the Russians agreed to return most of the territory conquered in the 1720s.

This agreement shifted the regional diplomatic focus to a looming Ottoman-Russian confrontation over control of the Black Sea region and provided for Nāder a military respite on his western border.

By the end of 1735, Nāder felt that he had gained enough prestige through a series of victories and had secured the immediate military situation well enough to assume the throne himself. In Feburary 1736, he gathered the nomadic and sedentary leaders of the Safavid realm at a vast encampment on the Moḡān steppe.

He asked the assembly to choose either him or one of the Safavids to rule the country. When Nāder heard that the molla-bāši (chief cleric) Mirzā Abu’l-Ḥasan had remarked that “everyone is for the Safavid dynasty,” he was said to have had that cleric arrested and strangled the next day (Lockhart, p. 99). After several days of meetings, the assembly proclaimed Nāder as the legitimate monarch.

The newly appointed shah gave a speech to acknowledge the approval of those in attendance. He announced that, upon his accession to the throne, his subjects would abandon certain religious practices that had been introduced by Shah Esmāʿil I (r. 1501–24) and had plunged Iran into disorder, such as sabb (ritual cursing of the first three caliphs Abu Bakr, ʿOmar, and ʿOṯmān, termed “rightly guided” by the Sunnites) and rafż (denial of their right to rule the Muslim community).

Nāder decreed that Twelver Shiʿism would become known as the Jaʿfari madòhab (legal school) in honor of the sixth Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣādeq (d. 765), who would be recognized as its central authority.

Nāder asked that this madòhab be treated exactly like the four traditionally recognized legal schools of Sunnite Islam. All those present at Moḡān were required to sign a document indicating their agreement with Nāder’s ideas.

Just before his actual coronation ceremony on 8 March 1736, Nāder specified five conditions for peace with the Ottoman empire (Astarābādi, p. 286), most of which he continued to seek over the next ten years.

They were:

(1) recognition of the Jaʿfari maḏhab as the fifth orthodox legal school of Sunnite Islam;

(2) designation of an official place (rokn) for a Jaʿfari imam in the courtyard of the Kaʿba [Perry, 1993, p. 854 and “Kaʿba,” in EI2 IV, p. 318 vs. Lockhart, p. 101] analogous to those of the Sunnite legal schools;

(3) appointment of a Persian pilgrimage leader (amir al-ḥajj);

(4) exchange of permanent ambassadors between Nāder and the Ottoman sultan; and

(5) exchange of prisoners of war and prohibition of their sale or purchase. In return, the new shah promised to prohibit Shiʿite practices objectionable to the Ottoman Sunnites.

Nāder tried to redefine religious and political legitimacy in Persia at symbolic and substantive levels.

One of his first acts as shah was to introduce a four-peaked hat (implicitly honoring the first four “rightly-guided” Sunni caliphs), which became known as the kolāh-e Nāderi, to replace the Qezelbāš turban cap, which was pieced with twelve gores (evocative of the twelve Shiʿite Imams).

Soon after his coronation, he sent an embassy to the Ottomans (Maḥmud I, r. 1730–54) carrying letters in which he explained his concept of the “Jaʿfari maḏhab” and recalled the common Turkmen origins of himself and the Ottomans as a basis for developing closer ties.

During this negotiation and subsequent ones, the Ottomans rejected all proposals related to Nāder’s Jaʿfari maḏhab concept but ultimately agreed to Nāder’s demands concerning recognition of a Persian amir al-ḥajj, exchange of ambassadors, and that of prisoners of war.

These demands paralleled the provisions of a long series of Ottoman-Safavid agreements, especially an accord, drawn up in 1727 but never signed, between the Ottoman sultan and Ašraf, the Ḡilzay Afghan ruler of Persia (r. 1725–29).

At the end of the 1148/1736 negotiations, both sides approved a document that mentioned only the issues of the ḥajj pilgrimage caravan, ambassadors, and prisoners because of disagreement over the Jaʿfari maḏhab concept.

Although no actual peace treaty was signed at that time, mutual acceptance of these other points became the basis for a working truce that lasted several years.

Συζητήσεις ανάμεσα στους Ιρανούς και την αντιπροσωπεία των Μογγόλων Γκορκανιάν της ‘Ινδίας’ έξω από το αφύλακτο Δελχί πριν την είσοδο ιρανικών στρατευμάτων

Nāder departed substantially from Safavid precedent by redefining Shiʿism as the Jaʿfari maḏhab of Sunni Islam and promoting the common Turkmen descent of the contemporary Muslim rulers as a basis for international relations.

Safavid legitimacy depended on the dynasty’s close connection to Twelver Shiʿism as an autonomous, self-contained tradition of Islamic jurisprudence as well as the Safavids’ alleged descent from the seventh Imam Musā al-Kāżem (died between 779 and 804). Nāder’s view of Twelver Shiʿism as a mere school of law within the greater Muslim community (umma)glossed over the entire complex structure of Shiʿite legal institutions, because his main goal was to limit the potential of Sunnite-Shiʿite conflict to interfere with his empire-building dreams.

The Jaʿfari maḏhab proposal also seems intended as tool to smooth relations between the Sunni and Shiʿite components of his own army. In addition, the proposal had economic implications, since control of a ḥajj caravan would have provided the shah with access to the revenue of the lucrative pilgrimage trade.

Nāder’s focus on common Turkmen descent likewise was designed to establish a broad political framework that could tie him, more closely than his Safavid predecessors, to both Ottomans and Mughals.

When describing Nāder’s coronation, Astarābādi called the assembly on the Moḡān steppe a quriltāy, evoking the practice of Mughal and Timurid conclaves that periodically met to select new khans. In various official documents, Nāder recalled how he, Ottomans, Uzbeks, and Mughals shared a common Turkmen heritage.

This concept for him resembled, in broad terms, the origin myths of 15th century Anatolian Turkmen dynasties. However, since he also addressed the Mughal emperor as a “Turkmen” ruler, Nāder implicitly extended the word “Turkmen” to refer, not only to progeny of the twenty-four Ḡozz tribes, but to Timur’s descendants as well.

Nāder’s novel concepts regarding the Jaʿfari maḏhab and common “Turkmen” descent were directed primarily at the Ottomans and Mughals. He may have perceived a need to unite disparate components of the omma against the expanding power of Europe at that time, however different his view of Muslim unity was from later concepts of it. But both ideas had less domestic importance.

On coins and seals, and in documents issued to his subjects, Nāder was more conservative in his claim to legitimacy. For example, the distich on one of his official seals focused only on the restoration of stability: Besmellāh — nagin-e dawlat-e din rafta bud čun az jā / be-nām-e Nāder Irān qarār dād Ḵodā (In the name of God — when the seal of state and religion had disappeared from Iran / God established there order in the name of Nāder; Rabino, p. 52).

In a proclamation sent to the ulamaof Isfahan soon after the coronation, the Jaʿfari maḏhab was depicted as nothing more than an attempt to keep peace between Sunnites and Shiʿites.

The document explained that ʿAli would continue to be venerated as one especially beloved by God, although henceforth the Shiʿite formula ʿAli wali Allāh (ʿAli is the deputy of God) would be prohibited.

In contrast to the shah’s letters to foreign rulers, this proclamation did not even mention the Safavids (Qoddusi, p. 540).

Nāder’s domestic policies introduced major economic, military, and social changes. He ordered a cadastral survey in order to produce the land registers known as raqabat-e Nāderi. Because of the establishment of the Jaʿfari maḏhab, the Safavid framework of pious foundations was suspended (Lambton, p. 131), although their revenues were the main source of financial support for important ulama.

Only in the last year of his reign did Nāder decree the resumption of pious foundations.

After his accession to the throne, Nāder claimed the ruler’s privilege to issue coinage in his name. His monetary policy linked the Persian currency system to the Mughal system, since he discontinued the Safavid silver ʿAbbāsi and minted a silver Nāderi whose weight standard corresponded with the Mughal rupee (Rabino, p. 52).

Nāder also attempted to promote fixed salaries for his soldiers and officials instead of revenues derived from land tenure. Continuing a shift that had begun in the late Safavid era, he increased substantially the number of soldiers directly under his command, while units under the command of provincial and tribal leaders became less important.

Finally, he continued and expanded the Safavid policy of a forced resettlement of tribal groups (Perry, 1975, pp. 208–10).

Ο Ναντέρ Σάχης στον λαφυραγωγημένο Θρόνο του Παγωνιού

All these reforms can be viewed as attempts to address weaknesses that had emerged in the late Safavid era, but none solved the problems that were tied to larger trends in the world economy. Iran had suffered from a swift rise in the popularity of Indian silk in Europe during the last few decades of Safavid rule, a shift that dramatically reduced Iran’s foreign income and indirectly contributed to the draining of bullion away from Persian state treasuries (Matthee, pp. 13, 67–68, 203–06, 212–218).

This crisis, in turn, put more pressure on the provinces to produce tax revenue, which led provincial governors to take oppressive measures and fueled the Afghan revolt that had resulted in the Safavid collapse in the first place.

After his ascension to the throne Nāder’s main military task was the ultimate defeat of the remaining Afghan forces that had ended Safavid rule. After laying siege to Qandahar for almost a year, Nāder destroyed it in 1738 — the last redoubt of the Ḡilzi, who were led by Shah Ḥosayn Solṭān, the brother of Shah Maḥmud, who had been the first Ḡilzay to rule Persia (1722–1725). On the site of his camp Nāder built a new city, Nāderābād, to which he transferred Qandahar’s population and Abdāli Afghans.

The destruction of Qandahar completed the reconquest of territory lost since the reign of Shah Solṭān Ḥosayn. Nāder’s career now entered a new phase: the invasion of foreign territory to pursue dreams of a world empire that could resemble the domains of Chinghis Khan (d. 1227) and Timur. After the fall of Qandahar, many Afghans joined his army.

His pursuit of Afghans who had fled across the Mughal frontier grew into an invasion of India when Nāder accused the Mughals of providing them with shelter and aid. Nāder had appointed Reżā-qoli as his deputy in Iran. While his father was away, Reżā-qoli feared a pro-Safavid revolt and had Moḥammad Ḥasan (the leader of the Qajars between 1726 and 1759) execute Ṭahmāsb and his sons.

After a successful offensive that culminated in the final defeat of the Mughal forces at the battle of Karnāl near Delhi in February 1739, Nāder made the Mughal emperor Moḥammad Šāh (r. 1719–48) his vassal and divested him of a large part of his fabulous riches, including the Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor diamond. When the rumor spread that Nāder had been assassinated, the Indians attacked and killed his troops. In retaliation, Nāder gave his soldiers permission to plunder Delhi and massacre its inhabitants.

The peace treaty restored control of India to Moḥammad Šāh under Nāder’s distant suzerainty; it proclaimed Moḥammad Šāh’s legitimacy, citing the Turkmen lineage that he shared with Nāder (Astarābādi, p. 327). Nāder arranged a ceremony in which he placed the crown back on Moḥammad Shah’s head. To further emphasize Moḥammad Šāh’s subordinate status, he assumed the title šāhānšāh.

To further strengthen his ties to the Mughals, Nāder married his son Naṣr-Allāh to a great granddaughter of the Mughal emperor Awrangzēb (r. 1658–1707). His chroniclers represent his victory over Moḥammad Šāh as another sign of his similarity to Timur. The shah himself was so obsessed with emulating Timur that he moved, for a time, to Mashad (Lockhart, pp. 188–89, note 4).

While Nāder was invading India, Reżā-qoli was securing more territory for Nāder north of Balḵ and south of the Oxus river. His campaign aroused the ire of Ilbars, the khan of Khwarazm, and of Abu’l-Fayż (r. 1711–47), the Toqay-Timurid khan of Bukhara. When they threatened counterattacks, Nāder engaged in a swift campaign against them on his way back from India. He executed Ilbars and replaced him with a more compliant ruler, but this new vassal would soon be overthrown. Abu’l–Fayż, like the Mughal emperor, accepted his status as Nāder’s subordinate and married his daughter to Nāder’s nephew.

After the campaigns in India and Turkestan, particularly with acquisition of the Mughal treasury, Nāder found himself suddenly wealthy. He issued a decree canceling all taxes in Iran for three years and decided to press forward on several projects, such as creation of a new navy.

Nāder had sent his naval commanders at various times on expeditions in the Persian Gulf, particularly to Oman, but these missions were unsuccessful, in part because it was difficult to secure naval vessels of good quality and in adequate numbers. In the summer of 1741, Nāder began to build ships in Bušehr, arranging for lumber to be carried there from Māzāndarān at great trouble and expense. The project was not completed, but by 1745 he had amassed a fleet of about thirty ships purchased in India (Lockhart, p. 221, n. 3).

However, Nāder experienced several major setbacks after his return to Iran. In 1741–43 he launched a series of quixotic attacks in the Caucasus against the Dāḡestānis in retaliation for his brother’s death. In 1741, an attempt was made on Nāder’s life near Darband. When the would-be assassin claimed that he had been recruited by Reżā-qoli, the shah had his son blinded in retaliation, an act for which he later felt great remorse.

Marvi reported that Nāder began to manifest signs of physical deterioration and mental instability. Finally, the shah was forced to reinstate taxes due to insufficient funds, and the heavy levies sparked numerous rebellions.

In spite of mounting problems, in 1741 Nāder sent an embassy to the Ottomans to resubmit his 1736 proposal for a peace treaty. But Maḥmud I had just won wars against Russia and Austria and was not receptive.

The sultan rejected the shah’s claim to Iraq (a claim based on Timur’s earlier control of the province).

Then the Ottoman legal authority, the šayḵ al-Eslām, issued a fatwā (legal opinion) formally declaring the Jaʿfari maḏhab heretical.

In response, Nāder besieged several cities in Iraq in 1743, with no results, and in December of that year he signed a ceasefire with Aḥmad Pāšā, the Ottoman governor of Baghdad (d. 1747). Subsequently, Nāder convened a meeting of ulama from Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia in Najaf at the shrine of ʿAli b. Abi Ṭāleb (d. 661), the fourth of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs and the first Imam.

After several days of lively debate on the question of the Jaʿfari maḏhab, the participants signed a document which recognized the Jaʿfari maḏhab as a legitimate legal school of Sunnite Islam.

The Ottoman sultan, however, remained unimpressed by this outcome.

Ο Ναντέρ Σάχης στην μάχη του Καρνάλ που άνοιξε στα ιρανικά στρατεύματα διάπλατα τις πόρτες της Μογγολικής Αυτοκρατορίας της Ινδίας, των Γκορκανιάν

Nāder soon had to leave Iraq to suppress several domestic rebellions.

The most serious of these began near Shiraz in January 1744 and was led by Moḥammad Taqi Khan Širāzi, the commander of Fārs province and one of Nāder’s favorites.

In June 1744, Nāder sacked Shiraz, and by winter he had crushed these revolts.

He resumed his war against the Ottomans and defeated them in August 1745 at Baḡāvard near Yerevan.

Although Nāder’s victory led to new negotiations, his bargaining position was not strong because of new, large-scale domestic uprisings.

The shah dropped his demands for territory and for recognition of the Jaʿfari maḏhab, and the final agreement was based only on the long mutually acceptable positions regarding frontiers, protection of pilgrims, treatment of prisoners, and exchange of ambassadors (Lockhart, p. 255).

The agreement recognized the shared Turkmen lineage and ostensibly proclaimed the conversion of Iran to Sunnism.

Yet the necessity to guarantee the safety of pilgrims to the Shiʿite shrines (ʿatabāt-e ʿāliya) in Iraq reveals the formal character of this concession.

The treaty was signed in September 1746 in Kordān, northwest of Tehran.

It made possible the official Ottoman recognition of Nāder’s rule, and the sultan dispatched an embassy with a huge assortment of gifts in the spring of 1747, although the shah did not live to receive it.

Nāder had spent the winter and spring of 1746 in Mashad, where he formulated a strategy to suppress the plethora of internal revolts. He also oversaw the construction of a treasure house for his Indian booty at nearby Kalāt-e Nāderi.

The building complex that Nāder constructed within this natural mountain fortress, near his birthplace in northern Khorasan, became his designated retreat, and he created there a secure showplace for his accomplishments.

Nāder followed the nomadic custom of not staying long in any permanent capital city, and Kalāt and Mashad (in, as he saw it. a complementary relationship) served as his main official sites in ways that resembled capital cities of other nomadic empires.

Under Nāder’s patronage, Mashad flourished at the midpoint of a trading route between India and Russia and grew in importance as a major pilgrimage center with its Emam Reẓā shrine complex.

In June 1747, a cabal of Afšār and Qajar officers succeeded in killing Nāder.

The succession struggle embroiled Persia in civil war for the next five years.

Two months before the assassination, Nāder’s nephew ʿAli-qoli, son of his brother Ebrāhim (d. 1738), had risen in revolt, and in July he followed his uncle on the throne as ʿĀdel Shah (r. 1747–48).

Nāder’s grandson Šāhroḵ, although blinded after an earlier coup attempt, finally secured the throne in Khorasan in 1748 as a vassal of the Afghan Aḥmad Shah Dorrāni (r. 1747–73).

This former deputy of Nāder founded the Dorrāni dynasty and is credited with being the first ruler of an independent Afghan state.

Šāhroḵ ruled for almost fifty years until 1795, when Āqā Moḥammad Khan Qajar (r. 1779–97) deposed him, marking the end of the rule of the Afsharids in Iran.

Text and bibliography in detail:

Koh-i-Noor and Nadir Shah’s Delhi loot

The legendary treasure trove of Hindustan has changed hands en masse on two occasions, once in 1739, when it was taken by Nadir Shah, and then again in 1857, by the prize agents of the East India Company. Apart from these two conquests, a great many priceless gems and jewels were acquired by the early European traders in India and sold in Europe. Today, many of the world’s famous diamonds have been attributed conclusively to the 1739 sack of Delhi. The most well-known jewels and artifacts among them are listed below — the little compressed and crystallized charcoal that have wended their way through a labyrinth of mankind’s violent history.

During Nadir Shah’s homeward march from Delhi to Persia, he ordered all the acquired jewels to be decorated on a tent. The tent is described in great details by an eyewitness Abdul Kurreem, who accompanied Nadir Shah on his return journey, in his memoir:

“The outside was covered with fine scarlet broadcloth, the lining was of violet coloured satin, upon which were representations of all the birds and beasts in the creation, with trees and flowers, the whole made of pearls, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, amethysts, and other precious stones: and the tent poles were decorated in like manner.

On both sides of the Peacock Throne was a screen, upon which were the figures of two angels in precious stones. The roof of the tent consisted of seven pieces, and when it was transported to any place, two of these pieces packed in cotton, were put into a wooden chest, two of which were a sufficient load for an elephant; and the screen filled another chest.

The walls of the tent, the tent poles and the tent pins, which latter were of massy gold, loaded five more elephants; so that for the carriage of the whole required seven elephants. This magnificent tent was displayed on all festivals in the Dewan Khaneh at Heart, during the remainder of Nadir Shah’s reign. After his death, his nephew Adil Shah, and his grandson Shahrokh, whose territories were very limited, and expenses enormous, had the tent taken to pieces, and dissipated the produce.”

Ένα μικρό τμήμα από τον θησαυρό και τα κοσμήματα του Ναντέρ Σάχη

In the well-known book ‘The History of Nadir Shah’ published in the 18th century from London, James Fraser estimates that 70 crores of wealth was carried away by Nadir Shah from Delhi:

Jewels from emperors and amirs: 25 crores

Utensils and handles of weapons set with jewels, with the Peacock Throne, etc.: 9 crores

Money coined in gold and silver coins: 25 crores

Gold and silver plates which he melted into coins: 5 crores

Fine clothes and rich stuff, etc.: 2 crores

Household furniture and other commodities: 3 crores

Weapons, etc.: 1 crore

Peacock Throne

Ten years after Nadir Shah returned from India with unimaginable treasure in 1739, he was assassinated by his own guards. Immediately, the famed Peacock Throne was dismantled, and its gems and stones were cut out and dispersed in the world market, though the entire lot can never be accounted for.

The Peacock Throne or the Mayurasan has been described by many, including historians Abdul Hamid Lahori, Inayat Khan, and French travellers Bernier and Tavernier, but Tavernier’s account can be considered the most authentic as he was officially allowed to inspect it in the Mughal court by Aurangzeb.

Tavernier was a French gem merchant who travelled between Persia and India six times between 1630 and 1668. According to him, the throne was of almost the size of a bed, being 6 ft x 4 ft in dimension. There were four horizontal bars connecting its four legs, upon which 12 columns stand to hold a canopy. At the centre of each of the 12 columns, a cross design was made of a ruby surrounded by four emeralds.

There were 108 large rubies (100–200 carats), 116 large emeralds (30–60 carats), innumerable diamonds and gemstones studded in the throne made of solid gold. Its paraphernalia included cushions, swords, a mace, a round shield, and umbrellas — all studded with gemstones and pearls. The underside of the canopy was covered with pearls and diamonds. Besides, Abdul Lahori describes the throne and its well-known stones, including Koh-i-Noor, the Akbar Shah diamond, the Shah diamond, the Timur Ruby, and the Shah Jahan diamond.

Koh-i-Noor

This diamond — known as ‘Babur’s Diamond’ before 1739 — was acquired from the Kakatiya dynasty by Allauddin Khilji. When Ibrahim Lodi was defeated by Babur, it was apparently handed over to Humayun by the mother of Ibrahim Lodi to guarantee the family’s safety. However, other sources say that it was gifted to Humayun by the Gwalior Royal Family.

Thereafter, it was presented by Humayun to the Persian Shah Tamasp (to garner his support to regain Hindustan), who then gave it to the Deccan Kingdom as a gift. It came back to the Mughals during Shah Jahan’s reign, via a Persian diamond dealer Mir Jumla, and remained with the Mughal emperors until 1739.

It is rumoured that Nadir Shah was tipped off that the emperor Muhammad Shah was hiding the diamond in his turban. Nadir Shah then invited the emperor to a customary turban-exchange ceremony to foster eternal supportive ties between the two empires. He could not believe his eyes when he found the diamond concealed within the layers of the turban, and exclaimed, ‘Koh-i-Noor!’ (‘Mountain of Light!’). Since then, it has been known by that name.

After Nadir Shah was assassinated, the diamond fell into the hands of Ahmad Shah Abdali of Kabul. After Abdali, it was ceded by the Afghans to Sikh King Ranjit Singh of Punjab. On his death-bed in 1839, Ranjit Singh willed the Koh-i-Noor to the Jagannath Temple at Puri. The British East India Company acquired it from his son (Duleep Singh) in 1843.

It is said that the diamond was kept by John Lawrence, who had absent-mindedly put the box in his coat pocket. When Governor General Dalhousie asked for it to be sent from Lahore to Mumbai, Lawrence asked his servant to find it; while rummaging through his wardrobe, the servant replied, “there is nothing here, Sahib, but a bit of glass!”

The Koh-i-Noor was transported to England aboard HMS Madea, with Dalhousie carrying it personally. It was cut and put in a crown by the crown jewellers Garrard & Co.; Queen Mary wore this crown to the Delhi Coronation Durbar in 1911.

Αντίγραφο του Κουχ-ι Νουρ

The Orloff

Prior to 1739, this unusual half-egg shaped diamond was known as the Great Mogul. After Nadir Shah’s murder, one of his soldiers sold it to an Armenian merchant, and it was acquired subsequently by the Russian nobleman Grigorievich Orlov. The nobleman presented it to his lover, the Grand Duchess Catherine, who mounted it in the Imperial Sceptre during her reign between 1762 and 1796.

Another version of the diamond’s history states that it was one of the eyes in a temple in South India, which was stolen by a French army deserter who had converted to Hinduism solely to gain access to the sanctum sanctorum of the temple to steal the diamond.

The Shah Diamond

This diamond remained in Iran for nearly a century until 1829, when the Russian diplomat and writer, Alexandr Griboyedov, was murdered in Tehran. Fearing a backlash from Russia, the grandson of Shah visited Moscow and presented the diamond as a gift to Russian Tsar Nicholas I.

The Great Table Diamond

Jean Baptiste Tavernier, a French traveller to India, mentioned a huge diamond of more than 400 carats that was set in the Peacock Throne, and called it the Diamanta Grande Table.

After Nadir Shah’s murder, the diamond was cut many times and distributed throughout the world. Researchers are still trying to locate all the pieces of this diamond, but only three have been confirmed to date — Darya-i-Noor (Sea of Light), Noor-ul-Amin (Light of the Eye), and Shah Jahan Table Cut.

The former two are among the Iranian Crown Jewels, as confirmed by a Canadian team from the Royal Ontario Museum that conducted a study on Iranian Crown Jewels in 1965.

The Darya-i-Noor is the most celebrated diamond among the Iranian Crown Jewels, and has a status similar to that of the Koh-i-Noor in the British Crown Jewels. The Shah Jahan Table Cut appeared mysteriously at a Christie’s auction in 1985, and was acquired by H.H.Sheikh Naseer Al-Sabah of Kuwait. It is assumed that it was not sold thereafter and remains in his family.

Timur Ruby

After Nadir Shah, Ahmed Shah Abdali of Kabul acquired a huge ruby along with the Koh-i-noor diamond, and later the Afghans ceded it to the Sikh King Ranjit Singh.

The British later acquired this mammoth 361 carat ruby from Maharaja Duleep Singh of Punjab. The names and dates of its six original owners are inscribed on the stone, as follows — Timur, Akbar (1612), Jahangir (1628), Aurangzeb (1659), Farrukhsiyar (1713), and Ahmad Shah Durrani (1754).

The ruby may be the one that was mentioned in Jauhar-i-Samsam while describing its acquisition by Nadir Shah from Muhammad Shah as “his majesty bestowed on Nadir Shah, with his own munificent hand, as a parting present, the peacock throne, in which was set a ruby upwards of a girih (three fingers’ breadth) in width, and nearly two in length, which was commonly called khiraj-i-alam or the tribute of the world”.

Below is a list of those few translucent rocks that are sprinkled around the world, of whose heritage we know about, thanks to the researchers and historians.

Till date, these are the only jewels that could have been conclusively traced back to Nadir Shah’s sack of Delhi in 1739. An unknown vast majority of the precious stones that Nadir Shah took with him is simply untraceable and most are probably lost in the passage of time.

Few may be lying in private collections, and then also, it is doubtful if their historicity is known even to their owners.

In this context, it does not really matter in which museum, or which city of the world these are located and preserved.

The important thing is that they are well conserved by experts to be passed down to future generations to cherish and appreciate these priceless items.

………….

Όταν δολοφονήθηκαν Ιρανοί στρατιώτες στο Δελχί, επακολούθησε τρομερή σφαγή ως αντίποινα.

Afsharid Dynasty (Nader Shah)

Nader Shah or King Nader (1688–1747), the founder of Afsharid Dynasty, an enigmatic figure in Iranian history ruled from 1736–1747 A.D.

Nader Shah, or Nader Qoli Beg was born in Kobhan, Iran, on October 22, 1688, into one of the Turkish tribes loyal to the Safavid shahs of Iran. He was the son of a poor peasant, who lived in Khorasan and died while Nader was still a child. Nader and his mother were carried off as slaves by the Ozbegs, but after death of his mother in captivity Nader managed to escape and became a soldier. Soon he attracted the attention of a chieftain of the Afshar in whose service Nader rapidly advanced. Eventually, the ambitious Nader fell out of favour. He became a rebel and gathered a substantial army.

In 1719 the Afghans had invaded Persia. They deposed the reigning Shah of the Safavid dynasty in 1722. Their ruler, Mahmoud Ghilzai (±1699–1725), murdered a large number of Safavid Princes, hacking many of them to death by his own hand. After he had invited the leading citizens of Esfahan to a feast and massacred them there, his own supporters assassinated Mahmoud in 1725. His cousin, Ashraf (±1700–1730), took over and married a Safavid princess.

At first, Nader fought with the Afghans against the Ozbegs until they withheld him further payment. In 1727 Nader offered his services to Tamasp II (±1704–1740), heir to the Safavid dynasty. Nader started the reconquest of Persia and drove the Afghans out of Khorasan. The Afghans suffered heavy losses, but before they fled Ashraf massacred an additional 3000 citizens of Esfahan. Most of the fleeing Afghans were soon overtaken and killed by Nader’s men, while others died in the desert. Ashraf himself was hunted down and murdered.

By 1729 Nader had freed Persia from the Afghans. Tamasp II was crowned Shah, although he was little more than a figurehead. While Nader was putting down a revolt in Khorasan, Tamasp moved against the Turks, losing Georgia and Armenia. Enraged, Nader deposed Tamasp in 1732 and installed Tamasp’s infant son, Abbas III (1732–1740), on the throne, naming himself regent. Within two years Nader recaptured the lost territory and extended the Empire at the expense of the Turks and the Russians.

In 1736 Nader evidently felt that his own position had been established so firmly that he no longer needed to hide behind a nominal Safavid Shah and ascended the throne himself. In 1738 he invaded Kandahar, captured Kabul and marched on to India. He seized and sacked Delhi and, after some disturbances, he killed 30000 of its citizens.

He plundered the Indian treasures of the Moghal Emperors, taking with him the famous jewel-encrusted Peacock Throne and the Koh-i Noor diamond. In 1740 Nader had Tamasp II and his two infant sons put to death. Then he invaded Transoxania. He resumed war with Turkey in 1743. In addition, he built a navy and conquered Oman.

Gradually Nader’s greedy and intolerant nature became more pronounced. The financial burden of his standing armies was more than the Persians could bear and Nader imposed the death penalty on those who failed to pay his taxes. He stored most of his loot for his own use and showed little if any concern for the general welfare of the country. Nader concentrated all power in his own hands.

He was a brilliant soldier and the founder of the Persian navy, but he was entirely lacking any interest in art and literature. Once, when Nader was told that there was no war in paradise, he was reported to have asked: “How can there be any delights there?”.

He moved the capital to Mashhad in Khorasan, close to his favourite mountain fortress. He tried to reconcile Sunnism with Shi’itism, because he needed people of both faiths in his army, but the reconciliation failed.

In his later years, revolts began to break out against his oppressive rule. Nader became increasingly harsh and exhibited signs of mental derangement following an assassination attempt.

He suspected his own son, Reza Qoli Mirza (1719–1747), of plotting against him and had him blinded. Soon he started executing the nobles who had witnessed his son’s blinding.

Towards the end, even his own tribesmen felt that he was too dangerous a man to be near. In 1747 a group of Afshar and Qajar chiefs decided “to breakfast off him where he should sup off them”. His own commanders surprised him in his sleep, but Nader managed to kill two of them before the assassins finished him off.

Nader was Persia’s most gifted military genius and is known as “The Second Alexander” and “The Napoleon of Persia”.

Although he restored national independence and effectively protected Iran’s territorial integrity at a dark moment of the country’s history, his obsessive suspicions and jealousies plunged Iran into political turmoil.

Little is known about Nader’s personal life. His grandiosity, his insatiable desire for more conquests and his egocentric behaviour suggest a narcissistic personality disorder and in his last years he seems to have developed some paranoid tendencies.

Nader was married four times and had 5 sons and 15 grandsons.

Afsharid Kings:

Nader Shah 1737–1747

Ali Gholi 1747–1748

Ebrahim 1748–1749

Shahrokh 1748–1749

http://www.iranchamber.com/history/afsharids/afsharids.php

Ασημένιο νόμισμα του Ναντέρ Σάχη κομμένο στο ιρανικό Νταγεστάν (σήμερα ανήκει στη Ρωσσία) το 1741

Nader Shah in Iranian Historiography

Warlord or National Hero?

By Rudolph Matthee · Published 2018

Western — European and North American — historiography generally portrays the years between the death of Louis XIV in 1715 and the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as having given birth to the modern world — a republican world founded on rational discourse and popular sovereignty, an empirically grounded, industrializing world built on progress and productivity, an aggressive, market-driven world espousing expansion as agenda and organizing principle.

In the traditional interpretation of Islamic Middle Eastern history, the “eighteenth century” projects an entirely different image. Rather than evoking energy and innovation, it conjures up stasis, decline and defeat. It speaks of exhausted, mismanaged empires that either succumbed to regional competitors or proved too weak to resist the juggernaut of European imperialism. Examples abound.

The state that had ruled Iran since the early sixteenth century, the Safavids, in 1722 collapsed under the onslaught of Afghan insurgents from the tribal periphery. The Ottomans, having failed to take Vienna in 1683, subsequently retreated against the Austrians and the Russians in the Balkans and later lost Egypt, first to the French and then to the Albanian warlord, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha. In the Indian Subcontinent, meanwhile, the once mighty Mughal Empire disintegrated and was brought into the British orbit.

Iran was doubly disadvantaged in this process of “regression.” The Ottomans suffered defeat and lost territory yet maintained military, diplomatic and commercial contact with the nations of Western Europe, the source of most of what was new at the time. The so-called Tulip Period of the early eighteenth-century reflects a fascination with things European among the ruling classes of Istanbul.

The Mughal state became tributary to the English East India Company and then was absorbed into the expanding British Empire. Yet that same process caused its elite gradually to become familiar with the ways and means of the new colonizers, creating models and generating ideas that helped the country keep in touch with developments in the wider world.

Iran, by contrast, in this period not just fell precipitously from stability to chaos, but in the process it became disconnected from the world in ways not experienced by the other “gunpowder empires.” Until the late seventeenth century the Safavids had been roughly on par with the Ottomans and the Mughals in their projection of wealth, power and cultural prestige.

Sophisticated Europeans knew Iran as the legendary land of the Sophy, a term personified by the most dynamic ruler of the dynasty, Shah ‘Abbas I (r. 1587–1629). Shah ‘Abbas had connected his country to the world in unprecedented ways. After proclaiming Isfahan his capital and endowing it with a newly designed awe-inspiring center, he had turned this centrally located city into a nexus of trade links between Europe, the Ottoman Empire, Russia, and India — and a favored destination for European traders and travelers, who saw in it a latter-day reflection of the Persian Empire as they imagined it from reading Herodotus, Strabo, and Pliny.

All this energy and efflorescence had come crashing down with the fall of Isfahan in 1722. The Afghan tribesmen who brought down the Safavid state failed to build their own on its ruins and were soon swept aside. What followed was seventy-five years of chaos and anarchy during which the Iranian plateau became remote and forbidding territory, run by warlords and mostly shunned by Westerners.

As the world was radically reconfigured in this period, Iranians continued to live in a rather self-congratulatory, inward-looking mode, secure in the knowledge that their country was, if no longer the center of the world, a place of consequence. In reality, Iran in this period rapidly “retreated” from the global scene as its ties with the outside world diminished in frequency and intensity. Iran’s short “eighteenth century,” the roughly seventy-five years that separate the fall of the Safavids from the rise of the Qajars, thus runs contrary to the perceived “global eighteenth century” and its presumed new level of (elite) connectivity.

This relative insularity was shattered in the early nineteenth century as the newly acceded Qajar regime (r. 1796–1925) with its largely tribally organized and poorly disciplined army suffered several terrible defeats against the well-equipped Russians, people the Iranians had always thought of and dismissed as bibulous, thick-skulled barbarians. As the Russians occupied large swaths of Iranian territory in the north — much of the southern Caucasus, comprising the modern countries of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan — the British intruded from the other side, the Persian Gulf.

Historians of late have turned away from this type of narrative with its focus on a golden age followed by decline and on great rulers and their deeds as organizing principles, to call for contingency, indeterminacy and attention to the common man. Yet, modern nationalism demands linearity and purposefulness, and shows little patience for revisionist complication.

Faced with the flux and reflux of history, nationalism likes to tell a story of loss and regeneration through resilience, of foreign-inflicted defeat followed by phoenix-like resurgence. It is therefore hardly surprising that modern Iranian historiography — and certainly the Iranian popular imagination — tends to portray the Safavids and the Qajars in starkly contrasting terms — the first symbolizing pride and glory, the second representing fecklessness and submissiveness.

Iranians have come to look back at the Safavid period nostalgically, as the last time their country was proud, independent, and the envy of the world. The Qajars, by contrast, the dynasty that would bring the country to the threshold of the modern age, count as spineless, corrupt rulers who blithely led the country into defeat and humiliation at the hand of foreigners, and who facilitated the country’s creeping incorporation into a Western-dominated imperialist network, preventing it from regaining its “natural” greatness.

The period in between is not so easily classified, for it seems neither a glorious moment in national history nor a century of potential splendor snatched away by foreign powers. Dark, seemingly directionless, and relatively short on written sources, the eighteenth century in Iranian history remains an awkward interlude.

Modern Iranian historians have nevertheless sought to weave this period into a continuous national narrative by adopting a Carlylean “great man” view of history, highlighting the stature of the two rulers who created identifiable albeit short-lived states and thus present a semblance of coherence and direction to Iranian history in an otherwise tumultuous period: Nader Shah (r. 1736–47) and Karim Khan Zand (r. 1763–69).

Both stand out, not just as the only two rulers who defied the period’s centrifugal forces, but as national heroes who revived Iran’s genius. The first, a brilliant warrior, redeemed the nation by restoring the honor it had lost with the fall of Isfahan to foreign tribesmen. The second represents the quintessentially Iranian search for justice.

Η νίκη του Ναντέρ Σάχη στο Μπαγκαβάρντ του Καυκάσου όπως απεικονίζεται από σύγχρονους Ιρανούς καλλιτέχνες

The first also stirred the Western imagination in ways the second never did — especially after he marched into India in 1739, ransacked Delhi and returned home with fabulous treasures. Indeed, the reception of Nader Shah in eighteenth-century Europe was as swift and dramatic as it was complex. The image it created, half brutal warlord, half national liberator, would significantly contribute to the image modern Iranians would construct of him.

Nader Shah: Scourge of God or National Hero?

The portrayal of Nader in the eighteenth-century West was the combined outcome of eyewitness accounts, Persian-language sources, and Enlightenment anxieties. Europeans, still puzzled by the sudden fall of the Safavids, learned of him even before he took power in 1736 as the warrior who reconquered Isfahan from the Afghans in 1729.