Naqsh-e Rustam: Cruciform Carved Tombs of the Achaemenid Dynasty & Relief of the Roman Emperor Valerian Captive and Kneeling before Emperor Shapur I (240–270)

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 19 Σεπτεμβρίου 2019. Στο κείμενό του αυτό, ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης παρουσιάζει όψεις της διαχρονικής σημασίας της αχαιμενιδικής νεκρόπολης του Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ, βασιζόμενος σε στοιχεία τα οποία παρέθεσα σε διάλεξή μου στο Καζακστάν (τον Ιανουάριο του 2019) σχετικά με την εσχατολογική σημασία ορισμένων ιερών χώρων του Ιράν.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/19/ναξ-ε-ρουστάμ-σταυρόσχημοι-λαξευτοί-τ/

================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής — Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

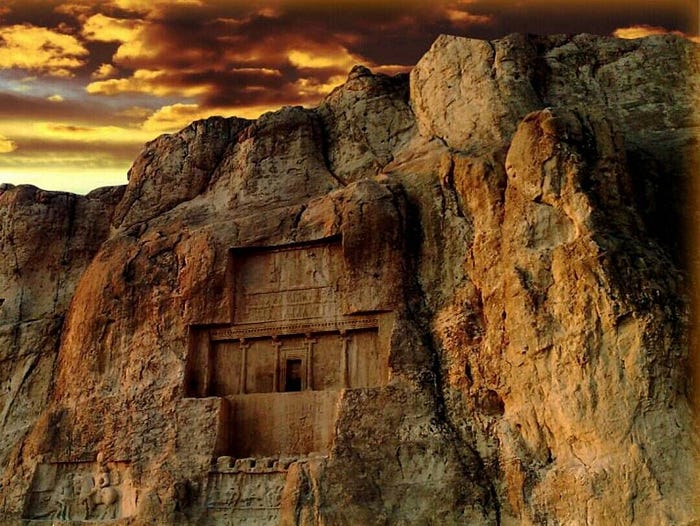

Πολύ πιο εντυπωσιακό από την κοντινή (10 χμ) Περσέπολη είναι το απόμακρο Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ (نقش رستم / Naqsh-e Rostam / Накше-Рустам, δηλαδή ‘η Εικόνα του Ρουστάμ’, ενός Ιρανού μυθικού ήρωα), ένας κορυφαίος προϊσλαμικός ιρανικός αρχαιολογικός χώρος που τα πελώρια μνημεία του, λαξευτά στον βράχο, ανάγλυφα ή οικοδομημένα αυτοτελώς, καλύπτουν 1200 χρόνια Ιστορίας του Ιράν, από την αρχή των Αχαιμενιδών (Χαχαμανεσιάν / 550–330 π.Χ.) μέχρι το τέλος των Σασανιδών (Σασανιάν / 224–651 μ.Χ.).

Εδώ βρισκόμαστε στα ιερά και τα όσια των Αχαιμενιδών: ο επιβλητικός βράχος λαξεύτηκε επανειλημμένα για να χρησιμεύσει ως αχαιμενιδική νεκρόπολη. Είναι αλήθεια ότι οι Πάρθες, οι οποίοι αποσχίσθηκαν από την Συρία των Σελευκιδών (το μεγαλύτερο κράτος των Επιγόνων) το 250 π.Χ. κι έστησαν την μακροβιώτερη ιρανική προϊσλαμική δυναστεία (τους Αρσακίδες — Ασκανιάν: 250 π.Χ. — 224 μ.Χ.), δεν ένοιωσαν κανένα δεσμό με τον συγκεκριμένο χώρο και δεν ανήγειραν κανένα μνημείο στην περιοχή. Άλλωστε, η Περσέπολη παρέμεινε πάντοτε εγκαταλελειμένη μετά την καταστροφή της από τον Μεγάλο Αλέξανδρο.

Και το Ιστάχρ, η μεγάλη σασανιδική πρωτεύουσα που είναι επίσης κοντά, ήταν μια μικρή πόλη, η οποία απέκτησε ισχύ μόνον μετά την άνοδο των Σασανιδών. Ουσιαστικά, για να αντλήσουν πειστήρια ιρανικής αυθεντικότητας και ζωροαστρικής ορθοδοξίας, οι Σασανίδες απέδωσαν εξαιρετικές τιμές στους σημαντικούς αχαιμενιδικούς χώρους δείχνοντας έτσι ότι επρόκειτο για ένα είδος επανάκαμψης ή παλινόστησης.

Για να επισκεφθεί κάποιος το Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ, το Ιστάχρ και την Περσέπολη σήμερα, πρέπει μάλλον να μείνει στην Σιράζ (شیراز / Shiraz / Шираз) που απέχει περίπου 40 χμ και είναι σήμερα η πέμπτη μεγαλύτερη πόλη του Ιράν και η πρωτεύουσα της επαρχίας Φαρς, δηλαδή της καθαυτό Περσίας. Αυτό είναι μια ακόμη απόδειξη του γεγονότος ότι κάνουν τρομερό λάθος όσοι Έλληνες από άγνοια αποκαλούν το Ιράν ‘Περσία’. Η Περσία είναι μόνον μια επαρχία του Ιράν κι οι Πέρσες είναι ένα μόνον από τα έθνη του Ιράν. Κι έτσι ήταν πάντα — για πάνω από 2500 χρόνια Ιστορίας του Ιράν. Η Σιράζ ήταν η πρωτεύουσα των ισλαμικών δυναστειών των Σαφαριδών και των Βουγιδών (Μπουαϊχί) που αποσπάσθηκαν από το Αβασιδικό Χαλιφάτο της Βαγδάτης στο δεύτερο μισό του 9ου χριστιανικού αιώνα.

Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ (Νουπιστάς/Nupistaš στα Αρχαία Αχαιμενιδικά)

Οι λαξευτοί αχαιμενιδικοί τάφοι στο Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ είναι ορατοί από χιλιόμετρα μακριά κι ένας ταξιδιώτης τους επισκέπτεται καλύτερα (με άπλετο φως και χωρίς σκιές) το μεσημέρι, καθώς οι προσόψεις των πελωρίων διαστάσεων λαξευτών τάφων στρέφονται προς τα νότια, καθώς ο τεράστιος βραχώδης λόφος έχει διάταξη από ανατολικά προς δυτικά.

Δεν κάνω μια τυπική αρχαιολογική παρουσίαση για να δώσω τις διαστάσεις με λεπτομέρειες, γι’ αυτό σημειώνω εδώ μόνον ενδεικτικά στοιχεία για τον τάφο του Δαρείου του Μεγάλου: η απόσταση του χαμηλότερου επιπέδου της πρόσοψης του τάφου από το έδαφος μπροστά σ’ αυτό (όπου στέκονται οι επισκέπτες του χώρου) είναι περίπου 15 μ.

Αυτό σημαίνει ότι όλοι οι τάφοι είναι υπερυψωμένοι κι έτσι λαξεύθηκαν και φιλοτεχνήθηκαν. Το ύψος της σταυρόσχημης πρόσοψης είναι 23 μ περίπου και η απόαταση του υψηλότερου επιπέδου της πρόσοψης του τάφου από την κορυφή του βραχώδους λόφου είναι σχεδόν 26 μ.

Η υπεράνω του κεντρικού τμήματος της σταυρόσχημης πρόσοψης πλευρά έχει ύψος περίπου 8.50 μ. Η υποκάτω του κεντρικού τμήματος της σταυρόσχημης πρόσοψης πλευρά έχει ύψος περίπου 6.80 μ. Το πλάτος των πλευρών αυτών είναι το ίδιο, περίπου 10.90 μ. Η λαξευτή αίθουσα του τάφου έχει μήκος (: βάθος μέσα στον βράχο) 18.70 μ, πλάτος 2.10 μ, και ύψος 3.70 μ. Περίπου 350 μ3 βράχου ανεσκάφησαν για να δημιουργηθεί η κοιλότητα η οποία διαμορφώθηκε ως ταφική αίθουσα, χωρισμένη σε τρία τμήματα.

Το Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ είχε κατοικηθεί ως χώρος για τουλάχιστον μια χιλιετία πριν φθάσουν οι Πέρσες στην περιοχή αυτή του Ιράν. Οι πρώτοι κάτοικοι δεν είχαν καμμιά σχέση με Ιρανούς: ήταν Ελαμίτες.

Το Αρχαίο Ελάμ ήταν ένα αρχαίο έθνος και βασίλειο — τμήμα της Ιστορίας της Αρχαίας Μεσοποταμίας και όχι της Ιστορίας του Ιράν.

Οι Ελαμίτες ήταν τόσο αρχαίοι όσο και οι Σουμέριοι και ο πολιτισμός τους τεκμηριώνεται από τα αποκρυπτογραφημένα αρχαία ελαμικά που διακρίνονται σε δύο μεγάλες ιστορικές περιόδους και καλύπτουν την περίοδο από τα τέλη της 4ης προχριστιανικής χιλιετίας μέχρι το 640 μ.Χ., όταν ο Ασσουρμπανιπάλ της Ασσυρίας εξόντωσε το Ελάμ κι εξολόθρευσε το σύνολο του ελαμικού πληθυσμού.

Κέντρο του Ελάμ ήταν τα Σούσα στην Νότια Υπερτιγριανή, τα οποία οι Αχαιμενιδείς βρήκαν σε ερειπία, ανοικοδόμησαν και κατοίκησαν.

Ήδη στα χρόνια των Αχαιμενιδών τα ελαμικά ήταν μια νεκρή γλώσσα (αντίθετα με τα βαβυλωνιακά) την οποία έμαθαν οι Ιρανοί ιερείς και γραφείς από φιλομάθεια, χάρη στους Βαβυλώνιους δασκάλους τους.

Έτσι, πολλές αχαιμενιδικές αυτοκρατορικές επιγραφές υπήρξαν τρίγλωσσες, σε αρχαία αχαιμενιδικά περσικά (Old Achaemenid), βαβυλωνιακά και ελαμικά (Elamite) — όλα σφηνοειδή.

Στο Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ υπάρχουν και ελαμικά ανάγλυφα ήσσονος ωστόσο σημασίας σε σχέση με τα ιρανικά μνημεία.

Σύχρονοι γλωσσολόγοι θεωρούν τους Δραβίδες που κατοικούν το Ντεκάν, δηλαδή το νότιο μισό της ψευτο-χώρας ‘Ινδία’, ως απογόνους των Αρχαίων Ελαμιτών, δεδομένου ότι υπάρχουν εμφανείς γλωσσολογικές ομοιότητες και συνάφεια ανάμεσα στα αρχαία ελαμικά και στις δραβιδικές γλώσσες.

Τέσσερις λαξευτοί τάφοι των Αχαιμενιδών βρίσκονται στο Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ με την εξής σειρά από τα αριστερά προς τα δεξιά: ο τάφος του Δαρείου Β’ (423–404 π.Χ.), ο τάφος του Αρταξέρξη Α’ (465–424 π.Χ.), ο τάφος του Δαρείου Α’ του Μεγάλου (522–486 π.Χ.), και του Ξέρξη Α’ (486–465 π.Χ.). Ένας πέμπτος ημιτελής λαξευτός τάφος πιθανολογείται ότι ετοιμαζόταν για τον Δαρείο Γ’ (336–330 π.Χ.).

Δυο σημαντικές επιγραφές σε αρχαία αχαιμενιδικά έχουν αναγραφεί στην πρόσοψη του λαξευτού τάφου του Δαρείου Α’, η πρώτη, περισσότερου ιστορικού, αυτο-βιογραφικού χαρακτήρα, στο άνω τμήμα της πρόσοψης του τάφου (γνωστή ως DNa) και η άλλη, περισσότερο θρησκευτικού και ηθικού χαρακτήρα, στο κάτω τμήμα της πρόσοψης (γνωστή ως DNb).

Επίσης, έχουν φιλοτεχνηθεί ανάγλυφες αναπαραστάσεις στρατιωτών των εθνών που συμπεριλαμβάνονταν στην αχαιμενιδική αυτοκρατορία και φέρουν σύντομες τρίγλωσσες αναφορές που δηλώνουν την ταυτότητα του κάθε αναπαριστώμενου στρατιώτη.

Επίσης στα αχαιμενιδικά χρόνια ανάγεται ένα κυβικού σχήματος κτήριο που ονομάζεται Κααμπά-γιε Ζαρντόστ, δηλαδή το Ιερό του Ζωροάστρη, σε αντιδιαστολή με τον Κααμπά της Μέκκας. Η ονομασία αυτή έχει δοθεί στο κτήριο κατά τα πρώιμα ισλαμικά χρόνια, όταν οι κατακτημένοι από τις ισλαμικές στρατιές Ιρανοί προσπαθούσαν να διατηρήσουν την ιστορική, θρησκευτική και πολιτισμική ταυτότητά τους.

Ωστόσο, μια σασανιδικών χρόνων επιγραφή πάνω στους τοίχους του κτηρίου διασώζει την μέση περσική ονομασία: Μπουν Χανάκ, δηλ. Θεμέλιος Οίκος. Η θρησκευτική λειτουργικότητα του κτηρίου είναι εμφανής, αν και υπήρξαν σύγχρονες επιστημονικές προσπάθειες να το δουν ως χώρο της αυτοκρατορικής στέψης.

Τέσσερις συνολικά επιγραφές σασανιδικών χρόνων έχουν αναγραφεί πάνω στους εξωτερικούς τοίχους του κτηρίου αλλά η πιο σημαντική ιστορικά είναι η περίφημη Επιγραφή του Καρτίρ, κορυφαίου αρχιερέα, ιδρυτή του Μαζδεϊσμού (ως ζωροαστρικής ορθοδοξίας), θεωρητικού της αυτοκρατορικής ιδεολογίας των Σασανιδών, και αυτοκρατορικού κήρυκα του σασανιδικού οικουμενισμού.

Κααμπά-γε Ζαρντόστ — το Ιερό του Ζωροάστρη

Τα μνημεία σασανιδικών χρόνων που σώζονται στο Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ είναι κυρίως τεραστίων διαστάσεων ανάγλυφα.

Διακρίνονται κυρίως τα εξής:

Α. Ενθρονισμός και Στέψη του Αρντασίρ Α’ (226–242), ιδρυτή της σασανιδικής δυναστείας

Β. Θρίαμβος του Σαπούρ Α’ (241–272), όπου αναπαρίστανται δύο ηττημένοι Ρωμαίοι αυτοκράτορες, ο Φίλιππος Άραψ (244–249), ο οποίος δεν είχε στρατιωτικά νικηθεί αλλά συνάψει μια ειρήνη με πολύ ταπεινωτικούς για την Ρώμη όρους, και ο Βαλεριανός (253–260), ο οποίος ηττήθηκε κι αιχμαλωτίσθηκε στην Μάχη της Έδεσσας της Οσροηνής (Ουρχόη, σήμερα Ούρφα στην νοτιοανατολική Τουρκία) το 260, είχε επακολούθως ταπεινωτική ζωή κι αργότερα οικτρό θάνατο στο Ιράν.

Γ. Ο Μπαχράμ Β’ (276–293) με τον Καρτίρ και Σασανίδες ευγενείς

Δ. Δύο ανάλυφα του Μπαχράμ Β’ έφιππου

Ε. Ενθρονισμός και Στέψη του Ναρσή (293–303)

ΣΤ. Ανάγλυφο του Χορμούζντ Β’ (303–309) έφιππου

Σχετικά με την ήττα του Βαλεριανού από το Σαπούρ Α’ και σχετικά με την παγκοσμίως κορυφαία μορφή του Καρτίρ θα επανέλθω.

Στην συνέχεια, μπορείτε να περιηγηθείτε στο Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ χάρη σε ένα βίντεο, να διαβάσετε επιλεγμένα άρθρα, και να βρείτε συνδέσμους για περισσότερη έρευνα αναφορικά με την προαναφερμένη θεματολογία.

Ο ηττημένος Βαλεριανός γονατιστός προ του Σαπούρ Α’

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Накше-Ростам: римский император Валериан, стоящий на коленях перед Шапуром I (после поражения у Эдессы в Осрене) 260 г. н.э.

https://www.ok.ru/video/1511021677165

Περισσότερα:

Недалеко от Персеполя находится огромный каменистый холм, который в настоящее время укрывает значительную часть 1200-летнего доисламского исторического и культурного наследия Ирана. Крестообразные и высеченные глубоко в скале императорские гробницы Дария I, Ксеркса I и других ахеменидских шахов. Рядом с ними можно полюбоваться великолепными барельефами Сасанидов, на которых изображены два римских императора, униженных перед Сасанидским шахом Шапуром I. Также можно увидеть другие снимки двора Сасанидов.

00:56 гробница Ксеркса I

01:40 Расследование Нарсеха

01:50 гробница Дария I Великого

02:26 Два барельефа Баграма II верхом на лошади

02:46 Триумф Шапура I с двумя униженными римскими императорами, Филиппом Арабским и (стоящим на коленях) Валерианом

03:02 гробница Артаксеркса I

03:31 Хормузд II верхом на лошади

03:41 гробница Дария IΙ

04:26 Баграм II верхом на лошади

04:43 Кааба-Зардошт (Храм Зороастра)

05:44 Расследование Ардашира I

06:10 Баграм II с дворянами Картиром и Сасанидами

Династии Ахеменидов принадлежат четыре гробницы со скальными рельефами. Они расположены в скалах на существенной высоте над землёй. Одна из гробниц принадлежит царю Дарию I, что установлено по надписям (522–486 до н. э.). Про остальные гробницы предполагают, что в них похоронены цари Ксеркс I (486–465 до н. э.), Артаксеркс I (465–424 до н. э.), и Дарий II (423–404 до н. э.).

Пятая неоконченная гробница, по предположениям, предназначалась царю Артаксерксу III, но более вероятно — царю Дарию III (336–330 до н. э.). Гробницы были заброшены после покорения Персии Александром Македонским.

На территории некрополя расположено квадратное в сечении здание высотой двенадцать метров (большая часть из которых находится ниже современного уровня земли) с единственным внутренним помещением. Народное название этого сооружения — «Куб Заратустры» (Кааб-е Зартошт).

Из научных версий наиболее распространена версия о том, что здание служило зороастрийским святилищем огня. По другой, реже упоминаемой версии, под сооружением может находиться могила Кира Великого. Однако ни одна версия не подтверждена документально.

На «Кубе Заратустры» имеются клинописные надписи, сделанные от лица Картира (одного из первых зороастрийских священников), портрет которого можно увидеть неподалеку в археологической зоне Накше-Раджаб.

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Накше-Рустам

Κααμπά-γε Ζαρντόστ — το Ιερό του Ζωροάστρη

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Naqsh-e Rostam: Roman Emperor Valerian kneeling in front of Shapur I (after the defeat at Edessa of Osrhoene) 260 CE

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240307

Περισσότερα:

Not far from Persepolis, there is an enormous rocky hill which shelters today a significant part of 1200 years of Pre-Islamic Iranian Historical and Cultural Heritage. Cruciform and hewn deep in the rock are the imperial tombs of Darius I, Xerxes I, and other Achaemenid shahs.

Next to them, one can admire the magnificent Sassanid bas-reliefs that depict two Roman emperor humiliated in front of the Sassanid Shah Shapur I and other snapshots of the Sassanid court.

00:56 Tomb of Xerxes I

01:40 Investigation of Narseh

01:50 Tomb of Darius I the Great

02:26 Two bas reliefs of Bagram II riding his horse

02:46 Triumph of Shapur I with two humiliated Roman emperors, Philip the Arab and (kneeling) Valerian

03:02 Tomb of Artaxerxes I

03:31 Hormuzd II riding his horse

03:41 Tomb of Darius IΙ

04:26 Bagram II riding his horse

04:43 Kaaba-ye Zardosht (the Shrine of Zoroaster)

05:44 Investigation of Ardashir I

06:10 Bagram II with Kartir and Sassanid noblemen

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ: Ανάγλυφο του Βαλεριανού γονατιστού προ του Σαπούρ Α’ & Σταυρόσχημοι Τάφοι Αχαιμενιδών

Περισσότερα:

Όχι μακριά από την Περσέπολη ένας τεράστιος βράχος αποτελεί σήμερα την παρακαταθήκη 1200 χρόνων προϊσλαμικής πολιτισμικής κληρονομιάς. Οι σταυρόσχημοι λαξευτοί τάφοι του Δαρείου Α’, του Ξέρξη και άλλων Αχαιμενιδών βρίσκονται δίπλα σε μεταγενέστερα σασανιδικά ανάγλυφα που απεικονίζουν την ταπείνωση δυο Ρωμαίων αυτοκρατόρων προ του Σάχη Σαπούρ Α’ και άλλα στιγμιότυπα της σασανιδικής αυλής.

00:56 Τάφος του Ξέρξη Α’

01:40 Ενθρονισμός και Στέψη του Ναρσή (293–303)

01:50 Τάφος του Δαρείου Α’

02:26 Δύο ανάλυφα του Μπαχράμ Β’ έφιππου

02:46 Θρίαμβος του Σαπούρ Α’ με δύο Ρωμαίους αυτοκράτορες, τον Φίλιππο Άραβα και τον Βαλεριανό γονατιστό

03:02 Τάφος του Αρταξέρξη Α’

03:31 Χορμούζντ Β’ έφιππος

03:41 Τάφος του Δαρείου Β’

04:26 Μπαχράμ Β’ έφιππος

04:43 Κααμπά-γιε Ζαρντόστ (το Ιερό του Ζωροάστρη)

05:44 Ενθρονισμός και Στέψη του Αρντασίρ Α’

06:10 Μπαχράμ Β’ με τον Καρτίρ και Σασανίδες ευγενείς

Naqsh-e Rostam (Persian: نقش رستم) is an ancient necropolis located about 12 km northwest of Persepolis, in Fars Province, Iran, with a group of ancient Iranian rock reliefs cut into the cliff, from both the Achaemenid and Sassanid periods. It lies a few hundred meters from Naqsh-e Rajab, with a further four Sassanid rock reliefs, three celebrating kings and one a high priest.

Naqsh-e Rostam is the necropolis of the Achaemenid dynasty (c. 550–330 BC), with four large tombs cut high into the cliff face. These have mainly architectural decoration, but the facades include large panels over the doorways, each very similar in content, with figures of the king being invested by a god, above a zone with rows of smaller figures bearing tribute, with soldiers and officials. The three classes of figures are sharply differentiated in size. The entrance to each tomb is at the center of each cross, which opens onto a small chamber, where the king lay in a sarcophagus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naqsh-e_Rostam

The Ka’ba-ye Zartosht is 46 metres (151 ft) from the mountain, situated exactly opposite Darius II’s mausoleum. It is rectangular and has only one entrance door. The material of the structure is white limestone. It is about 12 metres (39 ft) high, or 14.12 metres (46.3 ft) if including the triple stairs, and each side of its base is about 7.30 metres (24.0 ft) long. Its entrance door leads to the chamber inside via a thirty-stair stone stairway. The stone pieces are rectangular and are simply placed on top of each other, without the use of mortar; the sizes of the stones varies from 0.48 by 2.10 by 2.90 metres (1 ft 7 in by 6 ft 11 in by 9 ft 6 in) to 0.56 by 1.08 by 1.10 metres (1 ft 10 in by 3 ft 7 in by 3 ft 7 in), and they are connected to each other by dovetail joints.

The structure was built in the Achaemenid era and there is no information of the name of the structure in that era. It was called Bon-Khanak in the Sassanian era; the local name of the structure was Kornaykhaneh or Naggarekhaneh; and the phrase Ka’ba-ye Zartosht has been used for the structure since the fourteenth century, into the contemporary era.

Various views and interpretations have been proposed about the application of the chamber, but none of them could be accepted with certainty: some consider the tower a fire temple and a fireplace, and believe that it was used for igniting and worshiping the holy fire, while another group rejects this view and considers it the mausoleum of one of the Achaemenid shahs or grandees, due to its similarity to the Tomb of Cyrus and some mausoleums of Lycia and Caria.

Some other Iranian scholars believe the stone chamber to be a structure for the safekeeping of royal documents and holy or religious books; however, the chamber of Ka’ba-ye Zartosht is too small for this purpose. Other less noticed theories, such as its being a temple for the goddess Anahita or a solar calendar, have also been mentioned. Three inscriptions have been written in the three languages Sassanian Middle Persian, Arsacid Middle Persian and Greek on the Northern, Southern and Eastern walls of the tower, in the Sassanian era.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ka%27ba-ye_Zartosht

— — — — — — — — — — — — —

Διαβάστε:

Naghshe Rustam

Eras

Naghshe Rustam complex is within a 6-kilometer distance to Persepolis and is located in Haji Abad Mountains. This complex encompasses three eras:

Elamite relics belong to 2000–600 B.C.

Achaemenid relics belong to 330–600 B.C.

Sasanian relics belong to 224–651 A.D.

Mausoleum of Achaemenid Kings

Some of the greatest kings of Achaemenid’s tombs are in Naghshe Rustam. Xerxes (Khashayar Shah) (486 to 445 B.C.), Darius I (522 to 486 B.C.), Ardashir I (465 to 424 B.C.), and Darius II (424 to 405 B.C.) tombs are located in Naghshe Rostam.

The Tombs

The width of each tomb is 19 meters and the length is about 93 meters. The tombs are about 26 meters above the ground level.

Symbolism of the outer space of the tombs

The carving of the king with an arc in the hand is visible on top of the platform. This arc is a symbol of strength. In front of the king, the carving of Ahuramazda is visible. In this carving, two places are visible in which sacred fire is burning. In the right top of the picture, the carving of the moon is visible which shows the world instability.

In the bottom of the platform, the representatives of different nations are holding the kingdom throne. There are also columns; on top of each column, you can see a two-headed cow. Some roaring lions are visible in the bottom of the motifs. The lions are decorated with some lotus. Lotus is a symbol of sincerity and being free of any sin.

Mausoleum Structures

The entrance of each mausoleum is square shaped. These doors were being locked in ancient times. Additionally, Darius Mausoleum has some cuneiform writing. In this writing, Darius is praising Ahuramazda and he mentions his victories. He also speaks of his thoughts. The corridor in Darius Mausoleum has a length of 18.72 meters and a width of 3.70 meters. In this mausoleum, there are nine stone coffins which are dug in a stone row. They belong to the Great Darius, the Queen, and other relatives. Their dimensions are 2.1*1.5*1.5. Each tomb is covered with a big stone.

Kabaye Zartosht (Cube of Zoroaster)

In front of the Naghshe Rustam, in a whole, there is a beautiful cube that they call it the Cube of Zoroaster –who is an Iranian Prophet-. This building is made of big stones. The proficiency and precision used in cuttings and carvings in the black and white stones show the capability of the architectures in Achaemenid Dynasty. On top of the cube, there is a 2.5*2.5 square meters room. There are different beliefs about this room.

Some believe that Avesta (the religious texts of Zoroastrianism) which was written on 12000 cowhides has been stored in this room. Some others believe that this room is the tomb of Bardiya the son of Cyrus who was killed by his brother Cambyses.

Some of the historians believe that the sacred fire was stored in this room. Recently it is said that this room was an observatory. During the Sasanian Empire, some of the important governmental documents were kept. A Sasanian inscription is in three languages. This inscription mainly talks about the historical events in Shapour I in Iran and Rome battles in which the Valerian (Rome Emperor) was defeated and prisoned in Bishapur.

The Excavation of Naghshe Rustam

For the first time, it was excavated by Ernst Herzfeld (German archaeologist and Iranologist) in 1923. Herzfeld excavated the last vestiges of Sasanian towers. After that, this place was analyzed several times from 1936 to 1939. Some important heritage like Persian Inscriptions and some buried stone belonging to Sassanid Era were found. In central Excavations, they reach a building. And in the western parts, the last vestiges of two buildings with muddy bricks were found.

https://apochi.com/attractions/shiraz/naghshe-rustam/

============

Ο ηττημένος Βαλεριανός γονατιστός προ του Σαπούρ Α’

Naqš-e Rostam

Naqš-e Rostam, a perpendicular cliff wall on the southern nose of the Ḥosayn Kuh in Fārs, about 6 km northwest of Persepolis; the site is unusually rich in Achaemenid and Sasanian monuments, built or hewn out from the rock. The Persian name “Pictures of Rostam” refers to the Sasanian reliefs on the cliff, believed to represent the deeds of Rostam.

Achaemenid Period. The most important architectural remains are the tower called Kaʿba-ye Zardošt (Kaʿba of Zoroaster, Ar. kaʿba “cube, sanctuary”) and four royal tombs with rock cut façades and sepulchral chambers.

(1) The Kaʿba-ye Zardošt is a massive, built square tower, resting on three steps (7.30 x 7.30 x14.12 m) and covered by a flat pyramidal roof (Stronach, 1967, pp. 282–84; 1978, pp. 130–36; Camb. Hist. Iran II, pp. 838–48; Schmidt, pp. 34–49). The only opening is a door. But on all four sides there is a system of blind windows in dark grey limestone, set off by the yellow color of the general structure, between the reinforced corners, and the walls are covered with staggered rectangular depressions. Both systems have no other purpose than to relieve the monotony of the structure. A frieze of dentils forms the upper cornice. A staircase of 30 steps, eight of which are preserved, led to the door (0.87 x 1.75 m) in the upper part of the north wall. Originally, the two leaves of a door opened into an almost square room (3.72 x 3.74 x 5.54 m) without any architectural decoration and no provisions for lighting (Schmidt, p. 37).

There is an analogous, though much more decayed, structure, called Zendān-e Soleymān (lit. prison of Solomon), in Pasargadae (Stronach, 1978, pp. 117–37; 1983, pp. 848–52). Its stone technique does not yet show traces of the toothed chisel (Stronach, 1978, p. 132), and the building can thus be dated to the last years of Cyrus II the Great (r. ca. 558–530 BCE), whereas due to chisel marks the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt can be dated to the early years of Darius I (r. 522–486), around 500 BCE. The Achaemenid structures do not have exact prototypes, but their plan is comparable with those of the earlier Urartian tower temples (Stronach, 1967, pp. 278–88; 1978, pp. 132–34).

On the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt, three exterior sides bear the famous inscription of Shapur I. (r. 241–72 C.E.). The Res gestae divi Saporis (ŠKZ) was added in Greek on the south wall, in Sasanian Pahlawi (Parsik) on the east, and in Parthian (Pahlawik) on the west (Back, pp. 284–371), while the north wall with the entrance has remained empty. Beneath the Parsik version on the east wall, the high priest Kirdīr had his own inscription incised (Sprengling, pp. 37–54; Chaumont, pp. 339–80; Gignoux, pp. 45–48).

Evidently, in Sasanian times the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt — like the tower at Paikuli with the inscription of Narseh (r. 293–302; cf. Humbach and Skjaervø) — served, in addition to other functions, as memorial. Perhaps the two towers in Naqš-e Rostam and Pasargadae already had a similar significance in Achaemenid times, albeit this cannot have been their main function.

In Kirdīr’s inscription the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt is called “bun-xānak.” W. B. Henning proposed the translation “foundation house,” and concluded that the tower was of central religious significance. He suggested that the empty high room was destined “for the safe keeping of the records of the church and even more for the principal copy of the Avesta” (Henning).

Though other translations of “bun-xānak” have been discussed (Gignoux, pp. 28–29 n. 61), it seems the most convincing interpretation that these two towers served as depositories. The lack of any provision for the ventilation of a fire excludes the towers’ use as fire temples (Stronach, 1978, pp. 134–35).

Their staircases were designed “for the solemn ascent and descent of persons who in some manner attended the sacred structure” (Schmidt, p. 41). They indicate that the towers did not serve as royal tombs (Stronach, Camb. Hist. Iran II, p. 849 n. 2), because those have entrance walls that are smoothed beyond their facades, down to the original ground, to make them inaccessible.

N. Frye (1974, p. 386) first expressed the opinion that “the intention was . . . to build a safety box for the paraphernalia of rule in the vicinity of Persepolis as had been done at Pasargadae,” though E. F. Schmidt (p. 44) had dismissed the interpretation of the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt as depository. But Plutarch (46-after 119 C.E.) mentions in Artoxerxes 3 that at Pasargadae one temple belonged “to a warlike goddess, whom one might conjecture to be Athena” (Sancisi-Weerdenburg, p. 148).

At this sanctuary the Achaemenid kings were crowned. During the coronation ceremony the new monarch took a very frugal meal, and was dressed in the robes which Cyrus the Elder wore before assuming kingship. H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg was the first to identify the Zendān-e Soleymān as Plutarch’s temple (Gk. hieron).

Consequently, she interpreted this building, as well as the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt, as “coronation tower.” Her view that these towers had dynastic functions, rather than a purely religious significance and definitely no funeral purposes, has become widely accepted, though her suggestion that a sacred fire was also kindled in these towers can no longer be upheld.

(2) The Royal Tombs. In the cliff wall four monumental tombs are cut out from the native rock (Schmidt, pp. 80–107). The oldest tomb (Tomb I) has inscriptions that assign it to Darius I.

The other three (Tomb II-IV) can only tentatively be attributed to Xerxes (east-northeast of Darius I), Artaxerxes I (west-southwest of the tomb of Darius I) and Darius II (westernmost).

Δαρείος Α’ και τμήμα της μεγάλης επιγραφής επί της πρόσοψης του λαξευτού τάφου του Αχαιμενίδη σάχη

The four monuments follow the same pattern. But it is completely different from that of the older tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae, which is a built structure consisting of a stepped platform and a tomb with a gabled roof. The model was first used for Darius I and has no exact prototypes in the Near East, Egypt or Greece, though the stone technique is Urartian in origin (Calmeyer, 1975, pp. 101–7; Gropp, pp. 115–21; Huff, 1990, pp. 90–91).

Ο τάφος του Δαρείου Α’

The rock tomb is characterized by the contrast between a cruciform composition in relief on the exterior wall and a very simple interior of chambers and grave cists. The center of the relief ensemble is a facade that represents the front of a palace with four engaged columns. On this architectural component rests a throne bench (Gk. klinē, OPers. gathu in inscription DNa) that is supported by 30 representatives of the empire’s peoples. The throne bench in turn serves as the platform of a religious scene with king, fire altar, and divine symbols.

Δαρείος Α’ και η μεγάλη επιγραφή επί της πρόσοψης του λαξευτού τάφου του Αχαιμενίδη σάχη

The architectural register recalls the palace of the living monarch because the portico’s dimensions on the tomb of Darius I. are almost identical to those of his palace on the terrace of Persepolis (Schmidt, p. 81). A significant feature is the use of engaged columns, which appear on his tomb for the first time in rock architecture.

The so-called Median rock tombs, which are imitations of the Achaemenid monuments, do always show free standing columns (von Gall, 1966, pp. 19–43; 1973, pp. 139–154; 1988, pp. 557–82; “Dokkān”); the exception is the tomb of Qizqapan, where half columns have been placed on the rear of the antechamber (von Gall, 1988, pl. 23).

But at many tombs in the Median province, the originally freestanding columns have collapsed under the pressure of the superimposed rock. Consequently, there was not only the esthetic reason of creating the illusion that the antechamber’s front side and back wall were on the same level. More important were statical considerations. The architects and sculptors of the royal tombs used engaged columns because they could withstand the rock pressure despite their high slender shape.

Τα έθνη της Αχαιμενιδικής Αυτοκρατορίας, όπως αναπαρίστανται σε μια από τις επιγραφές της πρόσοψης του τάφου του Δαρείου Α‘

In the middle register, the mighty throne bench with its 30 armed carriers does not show a realistic scene, and is not considered pictorial evidence for the supposition of real processions on the roofs of Achaemenid palaces (Schmidt, p. 80). It rather is a simile of the Achaemenid empire, the throne bench of which is supported by its peoples, dressed in their distinctive costumes and headgears (Schmidt, pp. 108–118).

On the tombs of Darius I in Naqš-e Rostam and that of Artaxerxes II (r. 404–359 BCE) in Persepolis, inscriptions describe the peoples’ order, and this order seems to correspond with the official geographical records of the empire’s extension (Calmeyer, 1982, pp. 109–123). According to P. Goukowsky (p. 223; cf. Calmeyer, 1982, p. 113 fig. 3) the empire was divided in three concentric zones: Persians, Medians and Elamites live in the inner circle.

An axis is leading from the center to the east, listing Parthians, Arians, Bactrians, Sogdians, and Chorasmians. Then the enumeration turns southeast, naming Drangians, Arachosians, Sattagydians (Thataguš), Gandharans, and Indians and reaches Central Asia, where the haoma-venerating Scythians and pointed-hat Scythians already inhabit the periphery.

On a second axis leading to the south the Babylonians, Syrians, Arabians, and Egyptians (Mudraya) are aligned, whereas on a third axis to the northwest the Armenians, Cappadocians, Lydians (Sparda), and Ionians are represented. Finally in the western periphery there live the Scythians beyond the Sea, the Thracians (Skudra), and the Petasos bearing Ionians.

The Libyans (Putaya) and the Ethiopians (Kušiya) roam the empire’s southernmost countries. Two men stand outside the throne bench, and their hands help lifting the platform which is slightly elevated above the ground.

They are a Makan (Maka, i.e., Oman and probably also the region on the Persian side of the Gulf) and a Carian (Karka). P. Calmeyer (p. 120) has convincingly argued that their exceptional corner positions reflects that these two peoples inhabit the south and the west corners of the empire, at the shore of the ōkeanos which in antiquity was believed to flow around the inhabited earth (Gk. oikoumenē).

All men (Schmidt, figs. 39–50), with the exception of the Babylonian (ibid., fig. 50 no. 16), are wearing weapons, mostly daggers and swords, and some also pairs of javelins.

Bearing arms in the presence of the monarch was a sign of honor and trust, so that the unarmed Babylonian represents an act of deliberate humiliation.

Since Xerxes (r. 486–465 BCE) probably supervised the final work on the tomb of his father Darius I (Schmidt, pp. 116–18 part. 117), this humiliation is likely to reflect to repeated rebellions of the Babylonians against him as well as against his father.

The scene in the top register has religious significance. The king is standing on a three-stepped platform, his left resting on a bow, while his slightly lifted right hand points to the winged symbol hovering above the scene. Since the late 19th, early 20th century, the winged ensign with a human figure, emerging from a circle, has been understood as a representation of Ahura Mazdā (Root, pp. 169–79), and recent attempts to interpret this symbol as the royal genius Frawahr have been rejected.

The king faces a blazing fire altar, though he stands at a considerable distance, whilst the ensign of a disc with inscribed crescent is hovering in the upper right corner. In general, scholars agree that this scene shows how the king is worshipping the holy fire. But the gesture of the king’s right hand corresponds in all details with that of the right hand of the Ahura Mazdā symbol.

The representation thus stresses the close connection between the king and Ahura Mazdā, whose will is decisive for the king’s actions. This interpretation is supported by the Achaemenid royal inscriptions, which are directly related to the reliefs.

On tomb I, Darius I wears a headdress (Gk. kidaris) with an upper rim of sculptured stepped crenellations. Reliefs on the jambs of the southern doorway in Darius’s Palace (Tilia, pp. 58–59) indicate that this was the personal crown of Darius, which was also worn by Xerxes as long as he was crown prince (von Gall, 1974, pp. 147–51).

On Tomb II, which is ascribed to Xerxes, in the king’s crown the rest of a sculptured crenellation is visible (von Gall, 1974, pl. 134 no. 2; 1975 fig. 3), suggesting that this monument was completed before he became the absolute monarch (von Gall, 1974, p. 151). The representations of this late time show a straight cylindrical crown without any decoration. All succeeding rulers of the Achaemenid dynasty adopted this shape, allowing only minor deviations (von Gall, 1974, pp. 150–60; 1975, pp. 222–24).

Another invariable detail of the royal tombs is the discoid symbol hovering in the upper right corner. The inscribed crescent indicates its Assyrian origins. While it represents the moon god Sin in Assyrian art, on the Achaemenid tombs its meaning is difficult to comprehend. Opinions differ whether the symbol has to be interpreted as lunar or solar (cf. Root, pp. 177–78), and there are no written sources to corroborate either view. E. F. Schmidt (p. 85) interpreted the sign as a symbol of Mithra.

But the Persian moon god Māh is relatively well documented in the imagery of the Achaemenid seals. In the central panel above the fire altar scene of the rock tomb of Qizqapan, this type of moon god is also represented (von Gall, 1988, pp. 571–72). These images, in connection with other, though scanty, pictorial evidence (von Gall, 1988, p. 572 n. 55), suggest that the moon played a certain role in Achaemenid concepts of death and afterlife.

On the tomb of Darius, the framework of the throne bench shows three superimposed figures on each side. On the left, two dignitaries are inscribed as the lance bearer Gobryas (Gaubaruwa) and the bearer of the royal battle-ax Aspathines (Aspačina), while the lowest man is an unnamed guard (Schmidt, pp. 86–87). On the right, three unarmed men are clad in the long Persian garment. Their gesture of raising a part their upper garment to the mouth has been interpreted as an expression of mourning, comparable to the Greek custom (Schmidt, p. 87).

More recently, scholars have suggested that this gesture captures the imperative of ’do not pollute the holy fire’ (Hinz, p. 63 n. 4; cf. Seidl, p. 168) or shows respect for the king’s majesty (Root, p. 179), but both alternatives seem less convincing. Additional figures are on the side walls of the recesses into which the tomb facade was carved. On the left, there are three superimposed panels with guards holding long lances. On the right, three mourners who need be considered either courtiers or members of the royal family (Schmidt, p. 87) stand above each other.

Two larger cuneiform inscriptions, as well as legends with the names of Darius I, of his two supreme commanders, and of the 30 bearers of the throne bench, are found in the facade of Tomb I. One is in the top register, to the left of the king (DNa), and the other (DNb) stands in the architectural register, on three of the five panels between the half columns of the portico.

Both are written in three languages, but DNa in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (Weissbach, pp. 86–91), and DNb in Old Persian, Elamite and Akkadian (Hinz, pp. 52–62 including R. Borger’s edition of the Akkadian version). In the Seleucid period, an Aramaic version was added to DNb below the Elamite text (Frye, 1982).

In stark contrast to the rich architectural decoration of the façade, the interior is bare of any architectural and figural elements. The general layout is also best demonstrated with the tomb of Darius I: A long vestibule is running parallel to the facade, and three doors in the back wall of this vestibule are leading to three separate barrel-vaulted tomb chambers. In each tomb chamber, a trough-like cavity was hewn into the solid rock to hold a probably wooden sarcophagus or klinē. These cists were sealed with monolithic lids after the deposition of the corpses, but nothing has remained of the original interments.

Το άνω τμήμα της πρόσοψης του λαξευτού τάφου του Ξέρξη Α’

The combination of an oblique corridor and burial chambers with cists was preserved in the other three tombs, assigned to Xerxes (Tomb II), Artaxerxes (Tomb III), and Darius II (Tomb IV).

Yet they show inferior craftsmanship, because the chambers are not running axially, but obliquely to the facade. At Persepolis, the interior organization of the two tombs is also identical.

Τα έθνη της Αχαιμενιδικής Αυτοκρατορίας, όπως αναπαρίστανται σε μια από τις επιγραφές της πρόσοψης του τάφου του Ξέρξη Α’

(3) Other architectural remains. In the Center Test of his 1936 and 1939 excavations, E. F. Schmidt found a building (Schmidt, pp. 10 and 64). In the West Test, he discovered remains of two mud-brick buildings, as well as evidence of an enclosure of the royal tombs (ibid., pp. 10, 54–55). In the west of the cliff, a polygonal cistern (diam. 7.20 m) hewn out from the native rock was excavated (ibid., pp. 10, 65).

The Sasanian Period. A fortified enclosure ran around the major part of the sculptured cliff, and its west and east ends were abutting with the rock. Seven semicircular towers strengthened this structure (Schmidt, pp. 55–58, figs. 2, 4; cf. Trümpelmann, p. 41, fig. 68, drawing by G. Wolff). On the slope of the Hosayn Kuh, there are two cut rock structures in the shape of a čahārṭāq. They are generally assumed to be Sasanian fire altars, but D. Huff (1998, p. 80 pl. 10a; “Fārs,” pp. 353–54 pl. 3) identifies them as astōdāns.

Τις βιβλιογραφικές παραπομπές μπορείτε να βρείτε εδώ:

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/naqs-e-rostam

Ενθρονισμός και Στέψη του Αρντασίρ Α’

Μπαχράμ Β’, Καρτίρ και Σασανιδείς ευγενείς

Μπαχράμ Β’ έφιππος

Μπαχράμ Β’ έφιππος

Ενθρονισμός και Στέψη του Ναρσή

Ο Χορμούζντ Β’ έφιππος

=======================

Η νίκη του Σαπούρ Α’ επί των Ρωμαίων Αυτοκρατόρων Βαλεριανού (γονατιστού) και Φίλιππου του Άραβα

Ο Σαπούρ Α’ συλλαμβάνει τον Ρωμαίο αυτοκράτορα: όπως απεικονίζεται η σκηνή σε σμικρογραφία χειρογράφου του έργου του Φερντοουσί, εθνικού ποιητή του Ιράν (10ος-11ος αι.), Σαχναμέ (Βιβλίο των Βασιλέων)

Ο Σαπούρ Α’ όπως απεικονίζεται σε σμικρογραφία αντιγράφου του έργου του Φερντοουσί, εθνικού ποιητή του Ιράν (10ος-11ος αι.), Σαχναμέ (Βιβλίο των Βασιλέων), το οποίο φιλοτεχνήθηκε για τον Σαφεβίδη σάχη Ταχμάσπ τον 16ο αιώνα.

Επιπλέον:

Γενικά για τα μνημεία και τις επιγραφές:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naqsh-e_Rostam

ttps://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Накше-Рустам

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_Darius_the_Great

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DNa_inscription

Τα κείμενα των επιγραφών, φωτοτυπίες, μεταγραμματισμός κι αγγλική μετάφραση:

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/dna/?

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/dnb/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/dne/

https://www.livius.org/articles/place/naqs-e-rustam/

Το Ιερό του Ζωροάστρη:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ka%27ba-ye_Zartosht

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartir

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartir%27s_inscription_at_Naghsh-e_Rajab

Σχετικά με τον Σαπούρ Α’, τον Φίλιππο Άραβα, τον Βαλεριανό και την Μάχη της Έδεσσας της Οσροηνής (260 μ.Χ.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shapur_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valerian_(emperor)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Edessa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_the_Arab

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cameo_with_Valerian_and_Shapur_I

Η ταπείνωση και αιχμαλωσία του Ρωμαίου Αυτοκράτορα Βαλεριανού από τον Σαπούρ Α’ όπως αναπαριστάθηκε σε πίνακα του 16ου αιώνα από τον Γερμανό ζωγράφο Hans Holbein der Jüngere (Hans Holbein the Younger) — 1521. Ο καλλιτέχνης δεν είχε υπόψει του το σασανιδικό ανάγλυφο του Ναξ-ε Ρουστάμ και κανένας Ευρωπαίος ταξιδιώτης, έμπορος, διπλωμάτης ή ερευνητής δεν είχε φθάσει ακόμη εκεί αλλά οι Ευρωπαίοι διετήρησαν πολύ αρνητικές αναμνήσεις από τον Βαλεριανό, δεδομένου ότι ο Ρωμαίος αυτοκράτορας είχε κηρύξει διωγμούς κατά των Χριστιανών και Χριστιανοί συγγραφείς είχαν δικαιολογημένα χαρεί από το ελεεινό τέλος του Βαλεριανού που μάλιστα περιέγραψαν ως πολύ χειρότερο από το ιστορικά τεκμηριωμένο τέλος του.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Το περίφημο καμέο του Σαπούρ Α’ νικητή στην Έδεσσα της Οσροηνής (Ούρχα, σήμερα Ούρφα στην νοτιοανατολική Τουρκία) επί του Ρωμαίου αυτοκράτορα Βαλεριανού που αιχμαλωτίστηκε.

— — — — — — — — — — — —

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε PDF:

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/240270

No comments:

Post a Comment